‘And Ruth Berger persists in helping her, of which one cannot approve,’ said Verena. ‘It is no kindness to inadequate students to push them on. They should be weeded out for their own sake and find their proper level.’

Lady Plackett agreed with this, as all thinking people must. ‘She seems to be a very disruptive influence, the foreign girl,’ she said.

She had not been pleased when Professor Somerville had reinstated Ruth. There was something… excessive… about Ruth Berger. Even the way she smelled the roses in the quadrangle was… unnecessary, thought Lady Plackett, who had watched her out of the window. But on one point Verena was able to set her mother’s mind at rest. Ruth was not liked by the Professor; he seemed to avoid her; she never spoke in seminars.

‘And she is definitely not coming to Bowmont,’ said Verena, who was unaware of her mother’s interference in the matter of the Hardship Fund.

‘Ah, yes, Bowmont,’ said Lady Plackett thoughtfully. ‘You know, Verena, I find that I cannot be happy about you cohabiting in a dormitory with girls who do… things… in the backs of motor cars.’

‘I confess I have been worrying about that,’ said Verena. ‘Of course, one wants to be democratic.’

‘One does,’ agreed Lady Plackett. ‘But there are limits.’ She paused, then laid a soothing hand on her daughter’s arm. ‘Actually,’ she said, ‘I have had an idea.’

Verena lifted her head. ‘I wonder,’ she said, ‘if it is the same as mine.’

Chapter 16

‘Look at him,’ said Frances Somerville bitterly, handing her binoculars to her maid. ‘Gloating. Rubbing his hands.’

Martha took the glasses and trained them on the middle-aged gentleman with the intellectual forehead, making his way along the cliff path towards the headland.

‘He’s writing in his book,’ she said, as though the taking of notes was further proof of Mr Ferguson’s iniquity.

‘Well he needn’t expect me to give him lunch,’ said Miss Somerville. ‘He can go to The Black Bull for that.’

Mr Ferguson had arrived soon after breakfast, sent by the National Trust at Quin’s request to see if the Trust might interest itself in Bowmont. A man of impeccable tact, scholarly and mild-mannered, he had been received by Miss Somerville as though he had just crawled out of some particularly repellent sewer.

‘Maybe it won’t come to anything,’ said Martha, handing back the glasses. After forty years in Miss Somerville’s service, she was allowed to speak to her as a friend. ‘Maybe he won’t fancy the place.’

‘Ha!’ said Miss Somerville.

Her scepticism was justified. Though Mr Ferguson would report officially to Quin in London, he had already indicated that three miles of superb coastline, not to mention the famous walled garden, would probably interest the Trust very much indeed.

So there it was, thought Frances wretchedly: there the men in peaked caps, the lavatory huts, the screeching trippers. Quin had made it clear that even if negotiations went forward, he would insist on a flat in the house set aside for her use, but if he thought she would cower there and watch over the defilement of the place she had guarded for twenty years, he was mistaken. The day the Trust moved in, she would move out.

Perhaps if the letter from Lady Plackett hadn’t arrived just after Mr Ferguson took his leave, Miss Somerville would have reacted to it differently. But it came when she felt as old and discouraged as she had ever felt in her life and ready to clutch at any straw.

The Vice Chancellor’s wife began by reminding Miss Somerville of their brief acquaintance in the finishing school in Paris.

You may find it difficult to remember the little shy girl so much your junior, wrote Lady Plackett, who was not famous for her tact, but I shall always recall your kindness to me when I was homesick and perplexed. Miss Somerville did not remember either the homesick junior or her own kindness, but when Lady Plackett went on to remind her that she had been Daphne Croft-Ellis and that she had been presented in the same year as Miss Somerville’s second cousin, Lydia Barchester, the heel of whose shoe had come off as she left Their Majesties walking backwards, she read on with the attention one affords letters from those in one’s own world.

I was so excited to find that your dear nephew was on our staff and he may perhaps have mentioned that Verena, our only daughter, is taking his course. She is quite enchanted with his scholarship and expertise and at dinner recently they had a most engrossing conversation which was, I fear, quite above my head. You will, however, be wondering what emboldens me to write to you after so many years away in India and I will be entirely frank. As you know, dear Quinton runs a field course for our students at Bowmont. To this course Verena, as one of his Honours students, will, of course, be required to go and indeed she is looking forward to it greatly. However her position here at Thameside is delicate, as I know you will understand. She herself insists on being treated like all the other students as regards examinations and academic standards and there is certainly no difficulty there, for she is very clever. But socially, of course, she leads a different life, and we are careful not to encourage her classmates to take her presence at university functions for granted. Without some sense in which the Vice Chancellor and his family are different from ordinary academics, both staff and students, there could be no authority and no stability. This is something I need not explain to you.

So I am understandably anxious at the idea that Verena should share a dormitory with the other pupils. I gather that everyone ‘mucks in’ and sleeps in bunk beds and that there is no attempt to enforce any kind of discipline and though the students are, of course, the salt of the earth, some of them come from backgrounds which would, I think, make them uncomfortable if Verena was among them. Would it therefore be very impertinent of me to ask if my daughter could stay with you for the duration of the course? I understand that your nephew has his own rooms in the tower and that you are responsible for the domestic arrangements so that he would not need to concern himself with Verena unless he wished to do so. I myself shall be visiting the north at this time, and as Verena’s twenty-fourth birthday happens to fall on the last Friday of the course, I might perhaps invite myself just for that day before going on to make contact with dear Lord Hartington and the many other friends and connections of my own family which, after our long absence in India, I long to see again.

Do forgive me for being so blunt, but Verena is, understandably, so very dear to me and I cannot help wanting the best for her. And what could be better than to meet again the friend of my childhood, and protector?

With all good wishes,

Miss Somerville read the letter through twice and sat for a while, pondering. Then she rang for Turton.

‘Tell Harris I shall want the motor,’ she said. ‘I’m going to go over to Rothley.’

She was about to step into the old Buick, which she resolutely refused to let Quin replace, when a series of high-pitched yelps made her turn round and a shoe-sized puppy hurled itself at her legs, gathered itself up to leap onto the running board, missed, rolled over on to its back… and all the while its rat-like tail rotated in a frenzy and its unequal eyes gleamed with life affirmation and the prospect of togetherness.

‘Take it away,’ said Miss Somerville grimly. ‘And tell whoever let it out that if they don’t keep the door shut, I’ll have it drowned.’

The chauffeur repressed a grin, for the passion of the mongrel puppy for Bowmont’s mistress was a standing joke among the servants, but Miss Somerville, sitting stiffly in the back of the motor, could find no amusement in what had happened to her prize Labrador. The last of Comely’s thoroughbred puppies had been weaned and sold to excellent homes when, sooner than expected, she had come on heat again and spent a night away. The result of this escapade was a litter the like of which Miss Somerville, in thirty years of breeding dogs, could not have imagined in her most fevered dreams. By bullying various underlings on the estate, she had managed to find homes for the older puppies — but to get anyone to take the runt of the litter, with its arbitrary collection of whiskers, piebald stomach and vestigial legs, she would have had to put the villagers into stocks. And somehow this canine disaster seemed to go with all the other threats to her ordered world: with cowmen who sang opera and strangers with notebooks tramping over Somerville land.

The road to Rothley led past Bamburgh, once Bowmont’s rival to the north, and the causeway to Holy Island, before turning inland towards the Hall — a long, red sandstone building apparently kept aloft by fierce strands of ivy. The yapping of half a dozen Jack Russell terriers greeted her and presently she was in Lady Rothley’s small drawing room while her friend perused the letter.

‘One cannot really like the tone,’ she said presently, ‘but quite honestly, Frances, I do not see what you have to lose. At worst, Verena is a tiresome girl and you have her for a fortnight and at best…’

‘Yes, that’s what I thought. And she really does seem to be clever. She might interest him where sillier girls have failed.’

‘I’ll tell you one thing,’ said Lady Rothley ‘If she’s got Croft-Ellis blood in her, she’ll soon scotch any nonsense about giving Bowmont to the National Trust! If Quin marries Verena Plackett, they won’t get their hands on a square inch of midden. It’s not for nothing that their motto is What I have let no man covet! If there’s a meaner family in England, I’ve yet to hear of it.’ And seeing her friend’s face, ‘No, I’m joking, it’s not as bad as that — they’re good landlords and go back to the Conqueror. If the girl manages to get Quin, she’ll know how to behave.’

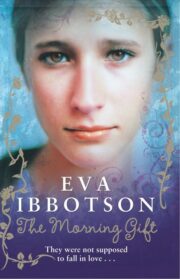

"The Morning Gift" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Morning Gift". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Morning Gift" друзьям в соцсетях.