‘I wonder what you think about Ashley-Cunningham’s views on bone atrophy as expressed in chapter five of his Palaeohistology?’ was the kind of thing the other students had to endure from Verena. ‘It wasn’t on our reading list, I know, but I happened to find it in the London Library.’

That Ruth might be a serious rival academically had not, at the beginning, occurred to Verena. A fey girl who conversed with sheep was hardly to be taken seriously. It was something of a shock, therefore, when the first essays were returned and she found that Ruth, like herself, was getting alphas and spoken of as someone likely to get a First. Verena set her jaw and decided to work even harder — and so did Ruth. Ruth, however, blamed herself, she felt besmirched, and at night when Hilda slept, she sat up in bed and spoke seriously to God.

‘Please, God,’ Ruth would pray, ‘don’t let me be competitive. Let me realize what a privilege it is to study. Let me remember that knowledge must be pursued for its own sake and please, please stop me wanting to beat Verena Plackett in the exams.’

She prayed hard and she meant what she said. But God was busy that autumn as the International Brigade came back, defeated, from Spain, Hitler’s bestialities increased, and sparrows everywhere continued to fall. And Ruth, her prayers completed, would spoil everything and get out of bed and take her lecture notes to the bathroom, the only place at Number 27 where, late at night, one could study undisturbed.

As term advanced, the talk turned increasingly to the field course to be held at the end of the month. Of this break in the routine of lectures, the research students who had been to Bowmont spoke with extreme enthusiasm.

‘You go out in boats and there are bonfires and cook-ups and on Sunday you go up to the Professor’s house for a whopping lunch.’

Ruth was prepared to believe all this, but she was adamant about not going.

‘I can’t possibly afford the fare, let alone all those Wellington boots and oilskins,’ she said. ‘And anyway, I have to prepare for Heini. I don’t mind, honestly.’

Pilly, however, did mind and said so at length, and so did Ruth’s other friends.

And Dr Felton minded. He did more than mind. He was absolutely determined to get Ruth to Bowmont.

For there was a Hardship Fund. It existed to help students in difficulties and it was under the management of the Finance Committee on which Roger sat, as he sat on most of the committees that came the department’s way since Quin had made it clear from the start that he was not prepared to waste his time in overheated rooms and repetitive babble.

The committee was due to meet on a Saturday morning just two weeks before the beginning of the course. Felton had already canvassed members from other departments and found only goodwill. The fund was healthily in credit, and everyone who knew Ruth Berger (and a surprising number of people did) thought it an excellent idea that it should be used to send her to Northumberland. It was thus with confidence and hope that Roger walked into the meeting.

He had reckoned without the new Vice Chancellor. Lord Charlefont had steered committees along at a spanking pace. Sir Desmond, whose degree was in Economics, thrived on detail: every test tube to be purchased, every box of chalk came under his scrutiny and at one o’clock, before the question of the Hardship Fund could be fully discussed, the committee was adjourned for lunch.

‘Do you really have to go back?’ asked Lady Plackett, who had hoped to persuade her husband to attend a private view.

‘Yes, I do. Felton from the Zoology Department is trying to get one of the students on to Somerville’s field course. He wants to use the Hardship Fund for that. It’s a very moot point, it seems to me — there’s a precedent involved. To what extent can not going on a field trip be classed as hardship? We shall have to debate this very carefully.’

‘It’s not the Austrian girl he wants the money for? Miss Berger?’

Sir Desmond reached for the agenda. ‘It doesn’t say so, but it seems possible. Why?’

‘If so, I would regard it as most inadvisable. As you know, Professor Somerville wanted to send her away — there was some connection with her family in Vienna. He was obviously aware of the danger of favouritism. And Dr Felton has been paying her special attention ever since, so Verena tells me.’

‘You mean —’ Sir Desmond looked up sharply.

‘No, no; nothing like that. Just bending the regulations to accommodate her. But if it got about that a fund intended strictly for cases of hardship was being used to give an unnecessary jaunt to a girl who is already here on sufferance, I think it could lead to all sorts of gossip and speculation. Better, surely, to keep the money for British students who are genuinely needy?’

‘Well, it’s a point,’ said Sir Desmond. ‘Certainly any kind of irregularity would be most unfortunate. She is a girl who has already attracted rather a lot of attention.’

‘And not of a favourable kind,’ said Lady Plackett.

‘What is it?’ asked Quin. He had just returned from the museum and was preparing to work late on an article for Nature.

‘That creep, Plackett.’ Roger’s spectacle frames looked as though they had been dipped in pitch. ‘He’s blocked the Hardship Fund — we can’t use it to get Ruth to Bowmont. It would set an unfortunate precedent if any student felt they could travel at the college’s expense!’

‘Ah. That’s probably Lady Plackett’s doing. She doesn’t care for Ruth.’ Quin, to his own surprise, found that he was very angry. He would have said that he did not want Ruth at Bowmont. Ruth being ‘invisible’ was bad enough here at Thameside — at Bowmont it would be more than he could stand, but the pettiness of the new regime was hard to accept.

‘Does Ruth want to go?’ he asked. ‘Isn’t the famous Heini due any day?’

‘Not till the beginning of November; we’ll be back by then,’ said Roger. He stared gloomily into the tank of slugs. ‘She wants to go right enough, whatever she says.’

‘You’re very keen to have her, you and Elke? Because she will benefit?’

‘Yes… well, damn it, you run the course, you know it’s the best in the country. But I wanted her to see the coast. I owe her…’

‘You what?’

Roger shrugged. ‘I know you think we make a pet of her — Elke and Humphrey and I… but she gives it all back and —’

‘Gives what back?’

Roger shook his head. ‘It’s difficult to explain. You prepare a practical… good heavens, you know what it’s like. You’re here half the night trying to find decent specimens and then the technician’s got flu and there aren’t enough Petri dishes… And then she comes and stares down the microscope as though this is the first ever water flea, and suddenly you remember what it was all about — why you started in this game in the beginning. If her work was sloppy it would be different, but it isn’t. She deserved more than you gave her for that last test.’

‘I gave her eighty-two.’

‘Yes. And Verena Plackett eighty-four. Not that it’s my business. Well, I reckon nothing can be done, not with you falling over backwards not to favour her because she sat on your knee in nappies.’

‘I do nothing of the sort, but you must see that I can’t interfere — it would only do Ruth harm.’ And as his deputy still stood there, looking disconsolate: ‘How are things at home? How is Lillian?’

Roger sighed. ‘No baby yet. And she won’t adopt. If only I hadn’t asked Humphrey to supper!’ Dr Fitzsimmons had meant well when he had told Roger’s wife about the drop in temperature a woman could expect before her fertile period, but he didn’t have to watch Lillian come out of the bathroom bristling with thermometers and refusing him his marital rights until the crucial time. ‘I shall be glad to go north for a while, I can tell you.’

‘I shall be glad to have you there.’

Ruth was not disappointed in the findings of the Finance Committee because she did not know of Dr Felton’s efforts on her behalf. But if she held firm over her decision to stay behind, she was perfectly ready to join in the speculations about Verena Plackett’s pyjamas.

For Verena, of course, was going to Northumberland, and what she would wear in bed in the dormitory above the boathouse occupied much of her fellow students’ thoughts. Janet thought she would turn into her wooden bunk in see-through black lace.

‘In case the Professor comes up the ladder at midnight with a cranial cast.’

Pilly thought a pair of striped pyjamas was more likely, with a long cord which she would instruct Kenneth Easton to tie into a double knot before retiring. Ruth, on the other hand, slightly obsessed by Verena’s pristine lab coat which she deeply envied, suggested gathered calico, heavily starched.

‘So you will hear her crackle in the night,’ she said.

But in fact none of them were destined to see Verena’s pyjamas, for the Vice Chancellor’s daughter had other plans.

If Leonie each night looked eagerly to Ruth for her account of the day, and Mrs Weiss’s dreaded ‘Vell?’ began her interrogation in the Willow Tea Rooms, Lady Plackett waited with more self-control, but no less avidity, for Verena’s news.

Verena reported with restraint about the staff, but where the students were concerned, she permitted herself to speak freely. Thus Lady Plackett learnt about the unsuitable — not to say lewd — behaviour of Janet Carter in the back of motor cars, the dangerously radical views of Sam Marsh, and the ludicrous gaffes made by Priscilla Yarrowby who had confused the jaw bone of a mammoth with that of a mastodon.

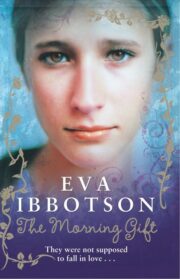

"The Morning Gift" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Morning Gift". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Morning Gift" друзьям в соцсетях.