‘To live with mice, to live with cats — for me it is the same,’ she said sadly.

Ruth too was troubled by the mice. She did not think that they could chew through the biscuit tin with the Princesses on the lid, but a great many documents of importance were collecting under the floorboards as Mr Proudfoot laboured on her behalf and it was disconcerting to feel that they provided a rallying point for nesting rodents.

But life in the university was totally absorbing. If there had been any anxiety about Heini’s visa, she could not have given herself to her studies as she did, but Heini wrote with confidence: his father had now found exactly who to bribe and he expected to be with her by the beginning of November. If Heini had any worries they were about the piano, but here too all was going well. For Ruth still worked at the Willow three evenings a week and the café was beginning to attract people from up the hill. She would not have taken tips from the refugees even if they could have afforded them, but from wealthy film producers or young men with Jaguars in search of ‘atmosphere’, she took anything she could get and the jam jar was three-quarters full.

Ruth’s response to news of her reprieve had been to ask Quin if she could see him privately for half an hour.

There was, she said, something she particularly wanted to tell him.

In trying to think of a place where they would meet no one of his acquaintance, Quin had hit on The Tea Pavilion in Leicester Square which no one in his family would have dreamt of frequenting, and was hardly a haunt of eminent palaeontologists. He had not, however, expected to score such a hit with Ruth who looked with delight at the Turkish Bath mosaics, the potted palms and black-skirted waitresses, obviously convinced that she was at the nerve centre of British social life.

The meeting began badly with what Quin regarded as an excessive outburst of gratitude. ‘Ruth, will you please stop thanking me. And I don’t take sugar.’

‘I know that,’ said Ruth, offended. ‘I remember it from Vienna. Also that it is upper class to put the tea in first and then the milk because Miss Kenmore told me that that is what is done by the mother of the Queen. But to expect me not to thank you is unintelligent when you have probably saved my life and found a job for my father and now are letting me return to college.’

‘Yes, well I hope you’ve thought that through properly. I don’t know if the courts interest themselves in the details of how we spend our days but you know what Proudfoot said about collusion. If Heini comes back and finds that there are unnecessary delays to your marriage he won’t be at all pleased. I think you should take that into consideration.’

‘Yes, I have. But I’m sure it’ll be all right and with Heini it’s more to do with being together, I told you. It would have happened before, but my father could never understand about the glass of water theory. One couldn’t even discuss it in his presence.’

‘What on earth is the glass of water theory?’

‘Oh, you know, that love… physical love… is like drinking a glass of water when you are thirsty; it’s nothing to make a fuss about.’

‘I don’t know if you could discuss it in my presence either,’ said Quin meditatively. ‘It sounds like arrant nonsense.’

‘Do you think so?’ Ruth looked surprised. ‘But anyway, I don’t think that he will mind about being married at once because of his career.’

‘I wonder. It’s my belief that the international situation will concentrate his thoughts wonderfully. I’ll bet he’ll want to claim you, and to do so legally, as soon as possible. However, I’ve made my point; if you’re sure you know what you’re doing, I’ll say no more.’

The plate of cakes he had ordered for Ruth now arrived and was greeted by her with rapture.

‘English patisserie is so… bright, isn’t it?’ she said, surveying the yellow rims of the jam tarts, the brilliant reds and greens of their fillings. She passed the plate to Quin who said he limited his consumption of bicarbonate of soda to medicinal purposes, and passed it back. ‘Actually,’ she went on, ‘I wanted to say something important about the annulment. That’s why I asked you to meet me. In case it goes wrong. I’m sure it won’t, but in case. You see, I’ve been talking to Mrs Burtt who is very intelligent and used to work for a lot of people who got divorced. Not annulled, but divorced. I didn’t realize how different that was.’

‘Who is Mrs Burtt?’

‘She’s the lady who washes up in the Willow Tea Rooms where I…’ She broke off, suspecting that Quin, like her father, might make a fuss on hearing that she still had an evening job. ‘It’s a place where we all go to. Anyway, she told me exactly what you have to do to get divorced.’

‘Oh, she did?’

‘Yes.’ Ruth bit into her jam tart. ‘You go to a hotel somewhere on the South Coast. Brighton is best because it has a pier and slot machines and you book into a hotel with a special lady that you have hired. And then you and the lady sit up all night playing cards.’ She looked up, her face a little troubled. ‘Mrs Burtt didn’t say what kind of card games — rummy, I expect, or perhaps vingt-et-un? Because for bridge you need more people, don’t you, and poker is probably not suitable? And then when morning comes you get into bed with the lady and ring for the chambermaid to bring you breakfast, and she comes and then she remembers you and the detective who has followed you calls her to give evidence and you get divorced.’

She sat back, extremely pleased with herself.

‘Mrs Burtt seems to be very well informed. And certainly if necessary I shall —’

‘Ah, but no! That is what I wanted to say. You’ve been so incredibly good to me that I couldn’t let you do that because I don’t think you would enjoy it, so I shall do it instead! Only of course I won’t hire a lady, I shall hire a gentleman which I shall be able to do by then because I shall have paid for Heini’s piano and got a job. Except that I don’t know any card games except Happy Families, but I shall learn and —’

‘Ruth, will you please stop talking rubbish. As though I would involve you in any squalid nonsense like that.’

‘It isn’t nonsense. It’s just as important for you to be free so that you can marry Verena Plackett.’

‘I wouldn’t marry Verena Plackett if she was the last —’ began Quin, caught off his guard.

‘Ah, but that is because you think she is too tall, but she could wear low heels or go barefoot which is healthy — and even if you don’t marry her there are all the ladies who jump at you from behind pyramids and the ones who leave scarves in your rooms — and I want to help.’

‘Well, you’re not going to help by getting mixed up in that sort of rubbish,’ said Quin. ‘Now tell me about your parents — how are they getting on and how is life in Belsize Park?’

Though she was clearly offended by Quin’s rejection of her plan, Ruth accepted the change of subject, nor did her hurt feelings prevent her from eating a second jam tart and a chocolate eclair, and by the time they left the restaurant, she was able to turn to Quin and make him a promise with her customary panache.

‘I know you don’t like to be thanked, but for tea everybody gets thanked and I want to tell you that from now on I will never again try to be alone with you, I will be completely anonymous; I will,’ said Ruth with fervour, ‘be nonexistent.’

Quin stood looking down at her, an odd expression on his face. Ruth’s eyes glowed with the ardour of those who swear mighty oaths, her tumbled hair glowed in the light of the chandeliers. A young man, passing with a friend, had turned to stare at her and bumped into the doorman.

‘That would interest me,’ he said thoughtfully. ‘Yes, your nonexistence would interest me very much.’

Ruth was as good as her word. She sat at the back of the lecture theatre (though no longer in a raincoat); she flattened herself against the wall when the Professor passed; her voice was never heard in his seminars.

This did not mean that she failed to ask questions. As Quin’s lectures opened more and more doors in her mind, she trained her friends to ask questions on her behalf, and to hear Pilly stumbling through sentences which had Ruth’s hallmark in every phrase, gave Quin an exquisite pleasure.

Nevertheless, Nature had not shaped Ruth for nonexistence, a point made by Sam and Janet who said they thought she was overdoing it. ‘Just because you knew him in Vienna, you don’t have to fall over backwards to keep out of his way,’ said Sam. ‘Anyway it’s a complete waste of time — one can see your hair halfway across the quad — I bet he knows exactly where you are.’

This, unfortunately, was true. Ruth leaning over the parapet to feed the ducks was not nonexistent, nor encountered in the library behind a pile of books, a piece of grass between her teeth. She was not nonexistent as she sat under the walnut tree coaching Pilly, nor emerging, drunk with music, from rehearsals of the choir. In general, Quin, without conceit, would have said he was a man with excellent nerves, but a week of Ruth’s anonymity was definitely taking its toll.

If Ruth was trying to keep out of the Professor’s way, Verena Plackett was not. She emerged each morning from the Lodge, punctual as an alderman, bearing her crocodile skin briefcase and carrying over her arm a spotless white lab coat, one of three, which her mother’s maids removed, laundered, starched and replaced each day. Verena continued to thank the staff on her parents’ behalf at the end of every lecture; she accepted only the sycophantic Kenneth Easton as her partner in practical; the liver fluke, seeing her coming, flattened itself obediently between glass slides. But it was in Professor Somerville’s seminars that Verena shone particularly. She sat in the chair next to the Professor’s, her legs neatly crossed at the ankle, and asked intelligent questions using complete sentences and making it clear that she had read not only the books he had recommended, but a great many others.

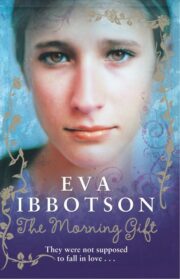

"The Morning Gift" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Morning Gift". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Morning Gift" друзьям в соцсетях.