Quin took out his handkerchief and wiped his brow. ‘Ruth, I’m sorry; I know you’ve settled in but —’

‘Yes, I have!’ she cried. ‘There’s so much here! Dr Elke showed me her bed bug eggs and they are absolutely beautiful with a little cap on one end and you can see the eyes of the young ones through the shell. And there’s the river and the walnut tree —’

‘And the sheep,’ said Quin bitterly.

‘Yes, that too. But most of all your lecture this morning. It opened such doors. Though I don’t agree with you absolutely about Hackenstreicher. I think he might have been perfectly sincere when he said that —’

‘Oh, you do,’ said Quin, not at all pleased. ‘You think that a man who deliberately falsifies the evidence to fit a preconceived hypothesis is to be taken seriously.’

‘If it was deliberate. But my father had a paper which said that the skull they showed Hackenstreicher could have been from much lower down in the sequence so that it wouldn’t be unreasonable for him to have come to the conclusions he did.’

‘Yes, I’ve read that paper, but don’t you see —’

Tempted to pursue the argument, Quin forced himself back to the task that faced him. That Ruth would have been an interesting student was not in question.

‘Look, there’s no sense in postponing this. I shall ring O’Malley and get you transferred to Tonbridge and until then you’d better stay away.’

She had turned her back and was absently retying the scarf, with its motif of riding crops and bridles, round Daphne’s neck. In the continuing silence, Quin’s disquiet grew. He remembered suddenly the child on the Grundlsee reciting Keats… the way she had tried to make a home even in the museum. Now he was banishing her again.

But when she turned to face him, it was not the sad handmaiden of his musings that he saw, not Ruth in tears amid the alien corn. Her chin was up, her expression obstinate and for a moment she resembled the primitive, pugnacious hominid beside whom she stood.

‘I can’t stop you sending me away because you are like God here; I saw that even before you came. But you can’t make me go to Tonbridge. I didn’t intend to go to university, I thought I should stay and work for my family. It was you who said I should go and when I thought you wanted me to come here I was so —’ She broke off and blew her nose. ‘But I won’t start again somewhere else. I won’t go to Tonbridge.’

‘You will do exactly as you are told,’ he said furiously. ‘You will go to Tonbridge and get a decent degree and —’

‘No, I won’t. I shall go and get a job, the best paid one I can find. If you had let me stay I would have done everything you asked me; I would have been obedient and worked as hard as I knew how and I would have been invisible because you would have been my Professor and that would have been right. But now you can’t bully me. Now I am free.’

Quin rose from his chair. ‘Let me tell you that even if I am not your Professor I am still legally your husband and I can order you to go and —’

The sentence remained unfinished as Quin, aghast, heard the words of Basher Somerville come out of his own mouth.

Ruth put a last flourish to the bow round Daphne’s neck.

‘You have read Nietzsche, I see,’ she said. ‘When I go to a woman I take my whip. How suitable that even the scarves your girlfriends leave behind have things on them for beating horses.’

But Quin had had enough. He went to the door, held it open.

‘Now go,’ he said. ‘And quickly.’

The guest list for Lady Plackett’s first dinner party was one of which any hostess could be proud. A renowned ichthyologist just back from an investigation of the bony fish in Lake Titicaca, an art historian who was the world expert on Russian icons, a philologist from the British Museum who spoke seven Chinese dialects and Simeon LeClerque who had won a literary prize for his biography of Bishop Berkeley. But, of course, the guest of honour, the person she had placed next to Verena, was Professor Somerville whom she had welcomed back to Thameside earlier in the day.

By six o’clock Lady Plackett had finished supervising the work of the maids and the cook, and went upstairs to speak to her daughter.

Verena had bathed earlier and now sat in her dressing-gown at her desk piled high with books.

‘How are you getting on, dear?’ asked Lady Plackett solicitously, for it always touched her, the way Verena prepared for her guests.

‘I’m nearly ready, Mummy. I managed to get hold of Professor Somerville’s first paper — the one on the dinosaur pits of Tendaguru, and I’ve read all his books, of course. But I feel I should just freshen up on ichthyology if I’m next to Sir Harold. He’s just back from South America, I understand.’

‘Yes… Lake Titicaca. Only remember, it’s the bony fishes, dear.’

Sir Harold was married but really very eminent and it was quite right for Verena to prepare herself for him. ‘I think we’ll manage the Russian icons without trouble — Professor Frank is said to be very talkative. If you have the key names…’

‘Oh, I have those,’ said Verena calmly. ‘Andrei Rublev… egg tempera…’ She glanced briefly at the notes she had taken earlier. ‘The effect of Mannerism becoming apparent in the seventeenth century…’

Lady Plackett, not a demonstrative woman, kissed her daughter on the cheek. ‘I can always rely on you.’ At the doorway she paused. ‘With Professor Somerville it would be in order to ask a little about Bowmont… the new forestry act, perhaps: I shall, of course, mention that I was acquainted with his aunt. And don’t trouble about Chinese phonetics, dear. Mr Fellowes was only a stop gap — he’s that old man from the British Museum and he’s right at the other end of the table.’

Left alone, Verena applied herself to the bony fishes before once again checking off Professor Somerville’s published works. He would not find her wanting intellectually, that was for certain. Now it was time to attend to the other side of her personality: not the scholar but the woman. Removing her dressing-gown, she slipped on the blue taffeta dress which Ruth had described with perfect accuracy and began to unwind the curlers from her hair.

‘I found it fascinating,’ said Verena, turning her powerful gaze on Professor Somerville. ‘Your views on the value of lumbar curve measurements in recognizing hominids seem to me entirely convincing. In the footnote to chapter thirteen you put that so well.’

Quin, encountering that rare phenomenon, a person who read footnotes, was ready to be impressed. ‘It’s still speculative, but interestingly enough they’ve come up with some corroboration in Java. The American expedition…’

Verena’s eyes flickered in a moment of unease. She had not had time to read up Java.

‘I understand that you have just been honoured in Vienna,’ she said, steering back to safer water. ‘It must have been such an interesting time to be there. Hitler seems to have achieved miracles with the German economy.’

‘Yes.’ The crinkled smile which had so charmed her had gone. ‘He has achieved other miracles too, such as the entire destruction of three hundred years of German culture.’

‘Oh.’ But this was a girl who only needed to look at a hound puppy for it to sink to its stomach and grovel — and she recovered her self-possession at once. ‘Tell me, Professor Somerville, what made you decide to start a field course at Bowmont?’

‘Well, the fauna on that coast is surprisingly diverse, with the North Sea being effectively enclosed. Then we’re opposite the Farne Islands where the ornithologists have done some very interesting work on breeding colonies — it was an obvious place for people to get practical experience.’

‘But you yourself? Your discipline? You will be there also?’

‘Of course. I help Dr Felton with the Marine Biology but I also run trips up to the coal measures and down to Staithes in Yorkshire.’

‘And the students stay separately — not in the house?’

‘Yes. I’ve converted an old boathouse and some cottages on the beach into a dormitory and labs. My aunt is elderly; I wouldn’t ask her to entertain my students and anyway they prefer to be independent.’

Verena frowned, for she could see problems ahead, but as the Professor looked as though he might turn to the left, where Mrs LeClerque, the unexpectedly pretty wife of Bishop Berkeley’s biographer, was looking at him from under her lashes, she plunged into praise of the morning’s lecture.

‘I was so intrigued by your analysis of Dr Hackenstreicher’s misconceptions. There seems no doubt that the man was seriously deluded.’

‘I’m glad you think so,’ said Quin, receiving boiled potatoes at the hands of a cold-looking parlourmaid. ‘Miss Berger seemed to find my views unreasonable.’

‘Ah. But she is leaving us, is she not?’

‘Yes.’

‘Mother was pleased to hear it,’ said Verena, glancing at Lady Plackett who was talking to an unexpected last-minute arrival: a musicologist just returned from New York whose acceptance had got lost in the post. ‘I think she feels that there are too many of them.’

‘Them?’ asked Quin with lifted eyebrows.

‘Well, you know… foreigners… refugees. She feels that places should be kept for our own nationals.’

Lady Plackett, who had been watching benignly her daughter’s success with the Professor, now abandoned protocol to speak across the table.

‘Well, of course, it doesn’t do to say so,’ she said, ‘but one can’t help feeling that they’ve rather taken over. Of course one can’t entirely approve of what Hitler is doing.’

‘No,’ said Quin. ‘It would certainly be difficult to approve of that.’

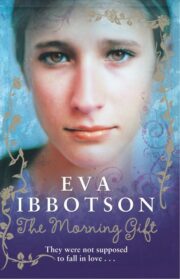

"The Morning Gift" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Morning Gift". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Morning Gift" друзьям в соцсетях.