Dr Felton agreed, obscurely comforted, and sent her to the Union where one of the third years was waiting to show newcomers round. When she had left, accompanying her handshake with that half-curtsy which proclaimed the abandoned world of Central Europe, he drew her form towards him and looked at it with satisfaction. Quin was always complaining that students these days were without personality. He’d hardly be able to level that charge at his new Honours student. Quin, in fact, would be very pleased. Whether he would feel the same about Verena Plackett, whose application form lay beneath Ruth’s, was another matter.

‘Vell?’ said Mrs Weiss, and cocked her head in its feathered toque at Ruth, determined to extract every ounce of information about her first day at college.

‘It’s going to be wonderful,’ said Ruth, setting a pot of coffee in front of the old lady, for she had not yet given up her evening job at the Willow Tea Rooms.

Everyone was in the café, including her own family, for Ruth’s return to her rightful place among the intelligentsia demanded celebration and discussion. They had heard about the niceness of Dr Felton, the majesty of Dr Elke and her parasites, the beauty of the river and the Goethe-loving sheep.

‘And Professor Somerville?’ enquired her father, who had only just arrived, for on Fridays the library stayed open late.

‘He isn’t back yet. He went to Scotland to try and join the navy,’ said Ruth, frowning over the slice of guggle she was bringing to Dr Levy. She had been certain that a man of thirty should not have to go to war. ‘But everyone says he is the most amazing lecturer.’

The lady with the poodle now arrived, and in deference to her the conversation changed to English.

‘You haf met the students?’ Paul Ziller enquired.

‘Only one or two,’ said Ruth, vanishing momentarily into the kitchen to fetch the actor’s fruit juice. ‘But there’s a girl starting at the same time as me — Verena Plackett. She’s the daughter of the Vice Chancellor and I expect she could choose any course she liked, but she’s doing the Palaeontology option too which shows how good it is.’

Ziller put down his cup. ‘Wait!’ he said, raising a majestic hand. ‘Her I haf seen!’

The eyes of the entire clientele were upon him.

‘How haf you seen?’ enquired Leonie.

Ziller rose and made his way to the wicker table on which lay the piles of magazines which the Misses Maud and Violet, bowing to the need of the refugees for the printed word, now brought downstairs. Ignoring Woman and Woman’s Own provided by the poodle-owning lady, and Home Chat, the contribution of Mrs Burtt, he sorted through the copies of Country Life, selected the issue he wanted, and began to turn the pages.

Considerable tension was by now generated, and Mrs Burtt and Miss Violet came out of the kitchen to watch.

‘Hah!’ said Ziller triumphantly, and held up the relevant page.

In the front of Country Life there is always a full-page photograph of a girl, invariably well bred, frequently about to marry someone suitable, but whether engaged or not, presenting a prototype of upper-class womanhood. Here are the Fenella Holdinghams who, in the spring, will marry the youngest son of Lord and Lady Foister; here the Angela Lathanby-Gores after their victory in the Highlingham Steeplechase… And here now was Verena Plackett — daughter of the newly appointed Vice Chancellor of Thameside — and not just Verena Plackett, but Verena Plackett gowned for presentation at Their Majesties’ courts in flesh-coloured satin with a train embroidered in lover’s knots of diamanté, and ostrich feathers in her hair.

Ruth, putting down her tray, was awarded first look, and studied her fellow student with attention.

‘She looks intelligent,’ she said.

Passed round, Verena seemed to give general satisfaction. Ziller liked her long throat, von Hofmann praised her collar bones and Miss Maud said she’d have known her anywhere for a Croft-Ellis by her nose. Only Mrs Burtt was silent, giving a small sniff which it was easy to attribute to class hatred.

But it was Leonie who looked longest at the picture and who, when she left the café, asked if she could borrow the magazine.

‘I’m not a snob,’ she said to her husband, who smiled a wise and matrimonial smile, ‘but to have Ruth back where she belongs… Oh, Kurt, that is so good.’

It was not till Ruth had gone to bed that Leonie set up her ironing board for she did not want her daughter to know how long she worked, or for how little money. But as she smoothed the fussy ruffles and frills on Mrs Carter’s blouse, she was humming a silly waltz she’d danced to in her girlhood and presently she put down the iron and once more examined Verena’s face.

She did not look particularly affable, but who did when confronted by a camera, and if her mouth turned down at the corners, this was probably some inherited trait and did not indicate ill temper. What mattered was that Ruth was back where she belonged. The daughter of a Vice Chancellor was an entirely suitable companion for the daughter of an erstwhile Dean of the Faculty of Science.

Not I but thou… the refrain of all cradle songs, all prayers with which parents, ungrudging, send their children forth to a better life than their own, rang through Leonie’s head. Verena and Ruth would be the greatest of friends — Leonie was quite sure of it — and nothing, that night, could upset her; not even the smell of burning lentils as the psychoanalyst from Breslau began, at midnight, to cook soup.

Chapter 13

Within three days of the beginning of term, Ruth was thoroughly at home at Thameside. To reach the university, she had to walk across Waterloo Bridge and that was like getting a special blessing for the coming day. There was always something to delight her: a barge passing beneath her with washing strung across the deck, or a flock of gulls jostling and screeching for the bread thrown by a bundled old woman who looked poor beyond belief, but was there each day to share her loaf — and once a double rainbow behind St Paul’s.

‘And it always smells of the sea,’ she told Dr Felton, who was becoming not only her tutor but a friend. ‘The rivers in Europe don’t do that — well, how could they with the ocean so far away?’

Dr Felton was a fine teacher, an enthusiast who shared with his students the amazing life of his creatures.

‘Look!’ he would cry like a child as he found, under the microscope, a cluster of transparent eggs from a brittle star, or the flagellum with which some infinitely small creature hurled itself across a drop of liquid. As she prepared slides and made her diagrams, Ruth was in a world where there was no barrier between science and art. Nor could anyone be indifferent to the extraordinarily successful lives led by Dr Elke’s tapeworms, untroubled by the search for food or shelter — living, loving, having their entire being in the secure world of someone else’s gut.

But if the staff were kind, and the work absorbing, it was her fellow students who made Ruth’s first days at Thameside so happy. They had worked together for two years, but they welcomed her without hesitation. There was Sam Marsh, a thin tousle-haired boy with the face of an intelligent rat, who wore a flat cap and a muffler to show his solidarity with the proletariat, and Janet Carter, a cheerful vicar’s daughter with frizzy red hair, whose innumerable boyfriends, of an evening, fell off sofas, got their feet stuck in the steering wheels of motor cars and generally came to grief in their efforts to attain their goal. There was a huge, silent Welshman (but not called Morgan) who was apt to crush test tubes unwittingly in his enormous hands… And there was Pilly.

Pilly’s name was Priscilla Yarrowby, but the nickname had stuck to her since her schooldays for her father was a manufacturer of aspirins. Pilly had short, curly, light brown hair and round blue eyes which usually wore a look of desperate incomprehension. She had failed every exam at least once, she wept over her dis-sections, she fainted at the sight of blood. The discovery that Ruth, who looked like a goose girl in a fairy tale, knew exactly what she was doing, filled Pilly with amazement and awe. That this romantic newcomer (with whom Sam was already obviously in love) was willing to help her with her work and to do so tactfully and unobtrusively, produced an onrush of uncontainable gratitude. Within forty-eight hours of Ruth’s arrival, it became almost impossible to prise poor Pilly from her side.

To the general niceness of the students there was one glaring exception. Verena Plackett’s arrival for the first lecture of term was one which Ruth never forgot.

She was sitting with her new friends, when the door opened and a college porter entered, placed a notice saying Reserved in the middle of the front bench, and departed again, looking cross. Since the lecture was to be given by Dr Fitzsimmons, the gangling, rather vague Physiology lecturer and was attended only by his students, this caused surprise, for Dr Fitzsimmons was not really a puller-in of crowds.

A few minutes passed, after which the door opened once more and a tall girl in a navy-blue tailored coat and skirt entered, walked to the Reserved notice, removed it, and sat down. She then opened her large crocodile-skin briefcase and took out a morocco leather writing case from which she removed a thick pad of vellum paper, an ebony ruler, a black fountain pen with a gold nib and a silver propelling pencil. Next, she zipped up the writing case again, put it back into the briefcase, shut the briefcase — and was ready to begin.

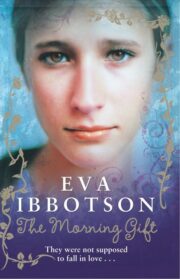

"The Morning Gift" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Morning Gift". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Morning Gift" друзьям в соцсетях.