On the death of Alfonso, Castelmelhor had returned to Portugal, made his peace with Pedro and was now in his service. I looked forward to seeing my old friend; but I had written to Pedro on impulse and was beginning to regret it.

For so long this country had been my home. The King and Queen were kind to me. I looked forward to my concerts…and my card games.

Manners and customs were easygoing here. I remembered the formality of life in Portugal. Did I want to leave familiar surroundings for somewhere which after all these years would be a strange place to me?

When the Count arrived in England, I was still very uncertain. I had come to the conclusion that I had taken the remark I had overheard about the “Dowager King” too seriously. It was merely the idle chatter of servants.

How understanding the Count was! I was able to open my heart to him, and he knew so much of what had happened to me. He reminded me that Portugal was not a rich country; one might say it was impoverished. As Queen of England, I should have certain revenues, he presumed. I told him that I had, although the marriage settlement, which had been promised to me, had never been paid in full or punctually. A great deal was owing to me. The Count said this should be paid in full before I left the country.

I had not thought about the money before, and I think I was so uncertain about leaving that I grasped every excuse to delay my departure.

This opened up a certain controversy. The Earl of Halifax, who was looking after my financial affairs, approached the Earl of Clarendon — who was the son of the first Earl whom I had known on my arrival. There was a suggestion from Halifax that Clarendon had been guilty of falsifying the accounts.

Clarendon, who was, of course, the King’s brother-in-law, immediately put the matter before James. The result was that the King summoned me to his presence.

As soon as I saw him I noticed a coldness in his manner toward me.

“It surprises me,” he said, “that you should have decided to leave the country without consulting me.”

“Your Majesty, I thought the matter would have been of little concern to you, so weighed down by state matters as you are at this time.”

“Of a certainty it is of concern to me. So you wish to leave us.”

“I am not sure,” I said.

“Yet you have written to your brother and he has sent Count Castelmelhor.”

“I wrote to him in a moment of despondency. They come to me now and then, and I felt I had to get away…to start anew.”

He looked at me with some compassion and I think he understood, for he said, more gently: “And now you are unsure?”

“Yes.”

“And this case…against my brother-in-law, is it wise?”

“They seem to have taken it out of my hands.”

“Clarendon has been accused of misappropriation of funds.”

“I did not wish to accuse him.”

“You will be ill advised to proceed with this case. But it is the law that you may do so, and I have no right to interfere with the law.”

“I understand,” I said.

“And, Catherine,” he went on, “it is for you to decide whether you wish to return to Portugal or stay. For my part, you will be welcome here for as long as you want to remain.”

ALTHOUGH CLARENDON had been found guity of misappropriation of funds, the lawsuit was a mistake. It branded me as a greedy, grasping woman — although I had only asked for what was legally mine.

People’s attitude changed toward me. I was no longer regarded as the meek woman who had taken a complacent attitude toward her husband’s infidelities, and sought to be on good terms with those about her. However, to be truthful, I did need the money which was due to me.

I had begun to realize that I must make provision for myself, for if I did decide to go to Portugal, I must be in a position to do so in some sort of comfort. Charles had been careless about money and consequently he had been in perpetual need of it.

I determined I should not be like that. I had to go back to Portugal and I did not want to throw myself on the charity of my brother.

If that was being hard and grasping — then I was. But in my own defense, I must say that I did not want to be a burden to others.

But the King, sadly, remained a little cooler than he had been toward me. And I think the people were only too ready to criticize me.

So…I would say that the court case was a mistake and I should not have been carried along by my advisors.

IN JUNE OF THAT YEAR 1688, three years after the death of Charles, the Queen was about to give birth to a child.

There was an air of excitement everywhere. This child was of the greatest importance. We were fast moving toward that situation which bedevilled so many kings and queens — the inability to produce an heir. Therefore there were great expectations and fears of disappointment.

It was very important that the birth of the child should be witnessed, for the country was at this time in a state of unrest.

James’s rule was giving cause for dissastisfaction and uneasiness. There was too much favor shown to Catholics and people were constantly referring to the golden days when King Charles was on the throne.

It seemed that Charles’s prophecies about James were coming true.

Accompanied by one or two of the married ladies of my household, I came to the place and was taken to the bedchamber where the birth was to take place.

What an ordeal for Mary Beatrice, to have her agonies witnessed by so many. But it was the royal custom, and in this case certainly proved to be a necessity.

How glad I was when at last I heard the cry of the child, and to my great joy, and that of everyone, it was a boy and looked likely to survive.

He was named James Francis Edward; and seven days after his birth he was christened and I was appointed his godmother.

IT WAS SOON AFTER the birth that the wicked rumors started.

There were many who were planning that the King should go, and, now that he had a son to follow him, there could be difficulties, for if the father were deposed, the son would be there to take the crown.

I believe that to be the reason for the rumors, because they certainly were absurd and without foundation.

Who first put the story about, I did not know, but very soon it was talked of throughout the court and in the streets. I was sure that the whole of country would soon be discussing it.

It was said that while the attendants crowded round the Queen’s bed, one of the King’s trusted servants had been standing by with a warming-pan in which was a live and healthy baby boy.

The Queen, they said, had given birth to a stillborn child; the warming-pan had been thrust into the bed and under cover of the bedclothes the infants had been changed and the healthy one brought out as the Queen’s child, while the stillborn child was hastily put into the warming-pan and taken away.

It was a preposterous story but, as Charles often said, people believe what they want to. Such a foolish rumor should have been dismissed immediately, but such was the unpopularity of the King and Queen that it persisted.

It was surprising that so much credence should have been given to it that it was necessary to call a meeting of the Privy Council, that all those who had been present at the birth could give evidence of having witnessed it.

I was one of these.

What an extraordinary occasion it was!

The King was present and I was given a chair beside him. The ladies who had been in the lying-in chamber were also present.

The King spoke to us and the Council listened attentively. “It grieves me,” he said, “that there has been this necessity of bringing you here. There has been much malicious gossip concerning my son, the Prince of Wales. There are those who maintain that the child which bears that title is not mine. Your Majesty, my lords and ladies here today, I am asking you who were present at the birth to declare what you know of it.”

I spoke first. “I was sent for when the Queen began her labor. I was in the bedchamber with her when the Prince of Wales was born.” And I went on to say that I had seen the Prince of Wales born and that the story of the warming-pan was an utter lie.

The others gave evidence in the same vein and what we said was written down and afterward we all signed the document.

That should have been enough, for we all declared that there had been only one baby and he was certainly the Prince of Wales. But the rumor persisted and people continued to whisper about the warming-pan baby.

AS THAT YEAR PASSED a certain menace crept into the atmosphere. If James was aware of it, he did not change his ways. He heard Mass in a manner which could only be called ostentatious. He prosecuted the convenanters in Scotland; he was at odds with the Church and seven bishops were prosecuted for seditious libel.

When they were declared “not guilty” there were loud cheers throughout the court; and when the people waiting in the streets heard the verdict there was loud singing and cheering and the entire city was in uproar.

This should have shown James how unpopular his policies were, and he should have known the English would never accept Catholicism, and that if he persisted in trying to promote it, his days would be numbered.

Oh James, I thought, why cannot you understand? Why do you do this foolish, dangerous thing? He was like his father, who had defied Parliament by his insistence on the Divine Right of Kings.

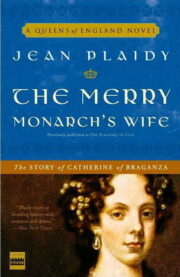

"The Merry Monarch’s Wife" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Merry Monarch’s Wife". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Merry Monarch’s Wife" друзьям в соцсетях.