“Fate was kind to me on that occasion, Jemmy…taking me from Newmarket before the appointed time. Bad luck for those who were working against me, but we must understand that Fate cannot please everyone all the time.”

“You must believe me…”

“Should the King be told by his bastard what he must do?”

Monmouth winced every time the King used the term. But I knew why Charles repeated it. It was to impress on this young man who he was and that he, the King, insisted that he should be known as such.

“If you will not believe me,” said Monmouth pathetically, “I must ask your leave to retire from court.”

“A sojourn abroad would be preferable to one in the Tower, I doubt not. And there is one other with whom you should intercede — your uncle, the Duke of York.”

“I will go to him if he will receive me, but it was to you I came first.”

The King was smiling at me. “He is a pretty boy, is he not?” he said. “He pleads well…so well, that he has an air of truth about him.”

“It is because I speak the truth,” said Monmouth. “Father, I beg of you. I have been foolish. I have been reckless. But never…never…I swear, in my life would I have harmed you.”

Charles was silent.

He said: “You should see the Duke of York. He is as concerned in this as I am. See if you can make your peace with him.”

“I will,” said Monmouth earnestly.

“And then,” said the King, “bring him here to me. As we were both to be the victims, it is only fitting that we should decide this matter between us.”

Monmouth knelt and kissed the King’s hand and, after doing the same to me, he went off to seek an audience with the Duke of York.

I knew of course that he would be forgiven.

Charles saw him again when the Duke of York was present. As I had predicted, Monmouth was forgiven, but as it was clear that he had been aware of the plot and had remained silent about it, it seemed desirable that he should stay away from the court for some time.

No charges were brought against him and after a while he set sail for the continent.

THERE WAS A MESSAGE from Portugal. My brother Alfonso had died at Sintra. Although it was many years since I had seen him, and he had been living in a kind of shadow land for so long, I was sad, remembering our childhood when he and Pedro had been little boys playing happily together; and I was sad thinking of my mother and what she would have thought of one of her sons taking the other’s throne…and his wife.

I believed Pedro must be remorseful now that his brother was dead, but at least Alfonso would be at peace.

The court went into mourning for my brother; and when it was over we slipped back into the old way of life.

Charles was as enamored as he had ever been of Louise de Keroualle. The fascination she exerted over him amazed me. The playactress Nell Gwynne was still important to him; and now that I was no longer in danger, I saw less of him.

The winter at that time was one of the harshest any living person remembered. The cold was intense. Never before had the Thames been frozen so hard. An ox was roasted on it and people crowded onto the hard ice to watch the spectacle.

Of course, the weather brought great hardship to the poor. Transport was impossible and ships could not get into the ports. There were prayers for relief in the churches, but it seemed that the frost continued for a very long time.

But spring was with us at last. Charles had not been very well for some time. He had always been so strong that he had been able to shrug off minor troubles, and so accustomed to perfect health that he was impatient with ailments. He hated to admit that he was feeling less than well and it seemed an affront to him that he should be so.

I could see that he had lost some of his vigor during that cruel winter.

Charles had not seemed well during the day. However, he supped as he often did with the Duchess of Portsmouth.

The following morning Lord Aylesbury, one of the Gentlemen of his Bedchamber, called on me in agitation.

“Your Majesty,” he said, “the King is unwell.”

I stood up in alarm, for Aylesbury looked very grave.

“What is wrong?” I asked.

“Dr. King is with him now. He has bled him.”

“Bled him?” I repeated blankly. “But…why?”

“The King was up early, as was his wont, Your Majesty. He went to his closet and was there longer than usual, and we became uneasy. When he came out he seemed to stagger…and then fell.”

“What was it? A fit?”

“I cannot say, Your Majesty. Dr. King seemed upset and said that bleeding was necessary without delay.”

“I must go to him at once,” I said.

When I reached his bedchamber I saw Charles sitting in a chair. He looked unlike himself…and when I came near I saw that his features were distorted.

“Oh…Charles,” I murmured.

He attempted to smile reassuringly.

Dr. King ordered that a warm iron should be put on his head. I thought he was dying. He could not be. He had always been so strong. He looked at me helplessly…as though he were apologizing for his weakness.

The Duke and Duchess of York appeared. James fell on his knees beside Charles’s chair and I saw real anguish in his face. I had always known of his affection for his brother. Poor James, he must be feeling many a qualm. He knew what Charles’s death would mean to him; he would be thrust into a position of danger, for many were opposed to him.

As the news spread through the street there was melancholy throughout the city. It was more than a rejection of James; it was a sign of the people’s love for the King. He was their Merry Monarch; he had come back and saved them from years of repression under Puritan rule. No matter what he had done, he had amused them with his amorous affairs; he had enchanted them with his smiles and his affable ways with all had won their hearts. There was never a king more loved by his subjects than Charles.

During the day he recovered a little.

The news seeped out and bells were rang. “He is recovered,” said the people. “He is going to live. Long may he reign.”

He was put into his bed and rested there, sitting up in bed, looking tired, but his features were no longer distorted and his speech was clear.

I sat by the bed and he held my hand, smiling at me. I was overcome with emotion.

“You are better,” I said. “You are going to recover.”

He lifted his shoulders characteristically.

“Life would be so empty without you,” I said.

“No,” he replied. “You will fill it.”

I said: “I have been foolish at times. I beg your pardon, Charles, I wish I had been better.”

His lips twisted into a wry smile. “You beg my pardon,” he said. “My poor dear Catherine. It is I who should beg yours…and I do…with all my heart.”

That night he had another seizure…more violent than the first…and we knew then that the end was near.

The Archbishop of Canterbury with the Bishops of London, Bath and Wells, and Durham were sent for.

There could be no hope now. Services were held in all the churches, and there was a hushed scene in the streets; people stood about and talked in whispers.

I asked the Duchess of York to come to me. We had always been good friends and I wanted her advice.

I said to her: “I know that the King was at heart a Catholic. He had contracted with Louis to be one and turn the country to Catholicism when the opportunity arose.”

“Louis paid him well for that,” said the Duchess, “and Charles accepted the payments knowing full well that the opportunity would never arise in his lifetime.”

“It has now,” I said.

“What do you mean? The King is dying.”

“I know that. He would want to receive the rites of the Catholic Church.”

She stared at me. “You are sure?”

I nodded. “I want you to explain to James.”

“I will,” she said.

I felt relieved. It was what he would have wished. It would be a secret, of course. What would the people’s reaction be if they knew their beloved King had died in the Catholic faith?

I saw James. He was haggard with anxiety. He said to me: “He shall have a priest. If they kill me for it, I will do this for his sake.”

I thanked him with deep gratitude.

TIME WAS PASSING. It was five days since Charles had had the first seizure. He was in great pain and all the remedies that had been heard of had been tried on him.

He retained his humor and asked the pardon of all those about him for being an unconscionable long time a-dying.

“Oh God,” I prayed, “how shall I live without him?”

The sixth day dawned — that black sixth of February — and the first seizure had taken place on the first of the month.

There was no hope now. I myself had been ill. I had fainted and my nose had bled profusely. Dr. King said that I must keep to my bed. That was impossible. I must be ready, lest he should call for me.

The King’s bedchamber was crowded with people…churchmen, peers, doctors, ambassadors…they must all be there to see the end of the King.

He needed to rest…to sleep…but a king cannot die like an ordinary man. They tried more remedies…and he lay there, dead pigeons at his feet, a warm iron on his head.

“Please let them leave him in peace,” I prayed.

The time was near and the Duke of York, assuming authority because he was almost King by this time, cleared the room. Father Huddleston was brought to Charles. He had had the forethought to dress himself as a clergyman of the Church of England and was taken up by a secret staircase, and Charles was given the sacrament in the rites of the Catholic Church.

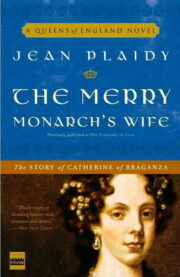

"The Merry Monarch’s Wife" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Merry Monarch’s Wife". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Merry Monarch’s Wife" друзьям в соцсетях.