Oates’s power was considerably subdued, but I had another enemy in Shaftesbury. His was the cause of Protestantism, and I was a Catholic. He did not accuse me of attempting to poison the King. He merely wanted to remove me so that the King might marry a Protestant queen and have children who would ensure a Protestant heir to the throne.

He knew that he could rely on considerable support throughout the country, and he brought in a Bill for the exclusion of the Duke of York and a divorce for the King that he might marry a Protestant and leave the crown to legitimate issue.

If Charles had wished to divorce me then, it would have been easy for him to have done so. He could have shrugged his shoulders in his nonchalant way and declared that it was his duty to do so.

I shall never forget how he stood by me in that time of danger. I knew how he hated trouble, how his great desire was to live a life of comfort and pleasure. His sauntering, his interest in the stars, his herbs, his dogs, the navy, planning buildings with the architects…that was the life he wanted to live. He had been so long in exile that these pleasures were of particular importance to him. He had had enough of conflict.

Yet with great vigor, he became my champion, and because of this I was ready to fight beside him. Indeed, what else could I do? To be parted from him was something I could not contemplate. It would be the end of everything I wanted. Anything, even this persecution, was better than that.

Charles made a point of going to the Peers to stress his abhorrence of the Bill, and to tell them that it was against his wishes that it should proceed. He would not see an innocent woman wronged. He was married to me and so he would remain. As for the Duke of York, he was the legitimate heir to the throne and only if he, the King, had legitimate heirs could that be changed.

Charles won the day. His wishes were respected and the Bill did not proceed.

Then William Bedloe died. This was quite unexpected, and it was another blow for Oates, for on his deathbed, Bedloe decided that he could not meet his Maker with so much on his conscience. So he repented and confessed that he had told many lies, that he knew nothing against me, except that I had given money to some Catholic institutions and was a Catholic myself. He admitted that accounts he had given of my attempts to poison the King were all lies.

Titus Oates must have been infuriated. Already he had lost some of his credibility by the acquittals of Sir George Wakeman and the Earl of Castlemaine. He might strut round in his episcopal robes — silk gown, cassock and long scarf — calling himself the nation’s savior, and enjoying his pension from the privy purse, but he must be suffering some qualms of fear and asking himself how long his glory would last.

I heard he had three servants to wait on him and dress him, as though he were royal; they vied for the honor of holding the basin in which he washed his hands. Everywhere people fawned on him, fearing that if they did not he might name them as conspirators and they find themselves under arrest.

He had so much to lose and Bedloe’s deathbed confession must have given him great concern.

His spirits were no doubt uplifted by the trial of William Howard, Viscount Stafford. There was as much interest in this as there had been in that of Sir George Wakeman; and there was a certain desperation about Oates and his followers now. There must be no more acquittals. Stafford was a noble lord…a man of integrity, son of the Earl of Arundel…and a Catholic.

He had been accused by Titus Oates, with several other Catholic lords, but Stafford was the one they decided to send for trial. I was of the opinion that this was because he was old, in frail health and perhaps less able to defend himself.

He was to be tried in Westminster Hall and I had a great urge to be there. I knew that, even if I were not mentioned as one of the conspirators, my complicity would be hinted at and I felt I must hear what was said.

A box was provided for me in the Hall and in this I sat, with some of my ladies.

It was a heart-rending experience to see that old man so persecuted. He was innocent, of course, and people in that hall knew it, but were afraid to say so.

Oates and his men gave evidence. There were two I had not heard of before — Dugdale and Tuberville. They swore that Stafford had tried to persuade them to murder the King. Oates affirmed that he had seen a document sent from the Pope to Stafford in which it was clear that Stafford was promoting Catholic interests.

The trial lasted for seven days. It was the same as before — lies, innuendoes and the continual suggestions that I was concerned in the plot to kill Charles.

Surely, I said to myself, everyone must see how false these people are. They are so obviously liars. Again and again they are proved wrong over details.

But there was fear in the hall. I could sense it. Titus Oates had a satanic power to terrify people. They did not seem to realize that if they all stood together against him they need not fear him.

Lord Chief Justice Sproggs had been persecuted after the acquittal of Sir George Wakeman. He had succeeded because of his powerfully expressed arguments. But for that, Sir George would have been condemned. It was pitiable. There was no such help for Stafford, and the verdict was what Oates demanded: Stafford was found guilty of treason. And the sentence for such a crime was hanging, drawing and quartering.

When I looked at that noble old man I felt sick with horror. When would all this end?

Why had I thought the power of Oates was waning? He was still an evil influence in the land.

I HAD RARELY SEEN Charles so distressed. Before him was the warrant for Stafford’s execution and it was to be signed by him.

There was anguish in his eyes.

“You cannot sign it,” I said.

“It is the law. He has been judged.”

“It is all so false,” I cried. “He is not guilty of treason. He would never join in a plot to kill you. You cannot believe it.”

Charles said. “He has had his trial and they have judged him guilty.”

“But he is not guilty.”

“They have judged him so.”

“If you refuse to sign…”

He shook his head. I understood. Even the King could not defy the law. His father had stood against the Parliament and what had happened to him must be a never-forgotten lesson to all the kings of England.

“I shall have to do my duty,” he said.

“That old man! But not to hang, draw and quarter. That is barbaric.”

“It is the law.”

He was still staring at the paper before him, reluctant to take up his pen.

He said: “Catherine, I must sign…”

I looked at him sadly, for he was so deeply disturbed.

To hang, to draw and quarter. I knew what that fearful sentence meant.

“I shall change that,” he said. “It shall be the axe. It is the least…and the most…I can do.”

Then he took up his pen and signed.

I believe that was something he regretted for the rest of his life.

SO THEY TOOK STAFFORD out to Tower Hill. Oates and his friends had been angered because the King had changed the sentence and they had some of their supporters on the scene, but their voices were silenced by the many who had gathered there and who did not think the verdict was just.

That should have been a further warning to Oates that his popularity was waning, for someone was heard to shout: “May God bless you, my Lord Stafford.”

Stafford made a declaration before he died. He persisted that he was entirely innocent. And a voice in the crowd was distinctly heard to say: “We believe you, my lord. You are innocent. This is a crime against justice.”

I was told that for a few moments the executioner looked perplexed, but like others, he would be afraid of what might happen to him if he did not do what was expected of him.

He lifted the axe and struck.

They buried Lord Stafford in the Chapel of St. Peter ad Vincula; and Charles was melancholy for some days and kept to his apartments.

WITH THE COMING OF SPRING there was more trouble.

Shaftesbury and his supporters had been so angry that their Bill to exclude the Duke of York and bring about my divorce had not been given a hearing that they were determined to bring it up again and force it through Parliament.

Then Edward Fitzharris appeared on the scene. He wanted to be another Titus Oates, which was not surprising, since Titus had done so well for himself.

The interesting point about Edward Fitzharris was that he had been associated with Louise de Keroualle, from whom doubtless he would have learned something of the art of spying.

His plan was to produce a document advocating the exclusion of the Duke of York from the succession because he was a foolish man unfit to rule, and that I should be removed because I had been suspected of being involved in a plot to poison the King.

It might have been that Louise de Keroualle was behind him in this. Being a Catholic, she could not hope to take my place and become Queen, but she was very ambitious for her son — who was also the King’s.

It was a slightly different version of the Popish Plot.

A document in the form of a letter, which was called “The True Englishman speaking Plain English in a letter from a friend to a friend,” was to be discovered in the house of some prominent member of the government and through it Fitzharris was to be a savior of his country, such as Titus Oates, the man on whom he was modelling himself.

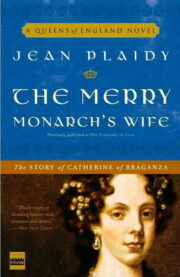

"The Merry Monarch’s Wife" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Merry Monarch’s Wife". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Merry Monarch’s Wife" друзьям в соцсетях.