I could guess. They were going to implicate me in their schemes.

Charles made me sit down and he sat beside me and put an arm about me.

“You must not fret,” he said. “There will be these rumors. They are nonsense. We’ll prove them to be nonsense. I no more suspect Wakeman than you do. I am sure we shall be able to prove that this Oates is nothing more than a troublemaker.”

I felt better when I listened to him, but after he had left me my anxieties returned.

THERE WAS A FEVER OF EXCITEMENT in the streets. Titus Oates was the country’s savior. He had discovered the plot in time and we were saved from the wicked papists — or at least we knew what they were planning and would be able to foil them.

Danby was all for setting the findings before the Privy Council. Charles was against it.

“It would only put the idea of murdering me into someone’s head,” he said. “As for these tales about the papists, I simply do not believe them.”

I was not sure that Danby did either, but it made the diversion he needed. With the whole country worrying about the papists, there was little interest in the misdemeanors of one of the ministers.

I could imagine the disappointment of Titus Oates and his fellow conspirators when they realized the King refused to take them seriously. Oates told Tonge that he must make their declaration before a Justice of the Peace, since the King had not wished to go before the Privy Council. This was the duty of a good citizen, insisted Oates. So, accordingly, this was done. He and Tongue went to the offices of Sir Edmund Berry Godfrey and set their “discoveries” before him. They gave their oath on this, and, realizing the nature of their revelations, Sir Edmund decided that he must bring the matter to the notice of the Council.

This made it impossible for even the King to thrust it aside, and as a result Oates and Tonge were summoned to appear and substantiate their accusations.

I think this might have put an end to the matter, but for two events which favored Oates.

There had been a number of arrests after Sir Edmund Berry Godfrey had received the declaration, and among them was a certain Coleman, who had been a secretary to the Duchess of York.

However, Oates was not clever enough to deceive Charles, although the Council was inclined to be swayed by him.

The man had a certain eloquence, but he allowed himself to be carried away by his own rhetoric, and this led him into pitfalls.

After the meeting Charles came to see me. It was one of his most lovable traits that, knowing my fears — not only for myself but for my servants such as Sir George Wakeman — his aim at that time was to assure me that, unfaithful husband though he might be, he could be a loyal friend.

He was quite gleeful on this occasion.

“That fellow is a fraud,” he said. “I’ll grant him this much. He knows how to tell a good story, but he gets carried away by the drama of his own invention, and that is where he goes awry. He should join the players. I’ll warrant he could give them some rousing plays.”

“Tell me…what did he say?” I asked.

“Well, he began by telling us that the Jesuits had decided they would kill me and, unless James agreed to put himself in their hands, he would go the same way. Père La Chaise has paid over ten thousand pounds already to be given to the assassin when the deed was done. I asked him if he had been told this. ‘No, Sire,’ he answered. ‘I was attending a meeting in your service, Sire, in the disguise of one of them. I overheard the discussion and saw Père La Chaise hand over the money to the messenger who was to bring it to England.’

“I said to him, ‘Mr. Oates, you were most assiduous on my behalf and I thank you. Tell me, where was this transaction made?’ He replied, ‘In the house of the Jesuits.’ ‘And which one was that?’ I asked. ‘It was the one close to the Louvre, Sire.’ ‘That is odd,’ I replied, ‘I had a long sojourn in Paris, so I know that the Jesuits do not have a house within a mile of the Louvre.’”

“He was lying,” I said.

“Of course he was lying. One would have thought that was obvious. But how people love a good conspiracy. It was clear that they did not want to stop this ingenious Mr. Oates in his flow. He would have us believe now that, on our behalf, he had labored long and faced many difficulties, for he implied what his fate would have been if those fanatical Jesuits had learned that he was a spy for His Protestant Majesty of England. When he was in Spain, he went on to tell us, he had been received by Don John of Austria. Mind you, it had needed a great deal of cunning planning to reach that gentleman. ‘Do describe him to me,’ I said. ‘Oh, Your Majesty, he is a tall and lean man, and swarthy.’ ‘You surprise me,’ I replied, ‘for when I met him he was short, fat and fair.’ All this confirmed what I had suspected. Our Mr. Oates is a fraud…a man who is determined to call attention to himself…to earn notoriety…and fortune…no matter whom he destroys on the way to it.”

I was relieved.

“Then this will be an end to this tiresome matter,” I said.

“I pray so. Though Danby will be reluctant to let it go. At the moment people have turned their attention from him. After all, what is a defaulting minister compared with a plot to murder the King?”

IN SPITE OF DANBY’S EFFORTS to keep the Popish Plot the issue of the day, the appearance of Titus Oates before the Council and the errors into which he had fallen discredited him to a certain extent and the conclusion that he was a cheat began to be expressed.

Then there was a change. It came about through Coleman, who had been one of those men whom Titus Oates had accused and who, on Oates’s evidence, had been arrested. Coleman was indeed a spy; he had received a pension from France; he was in the service of Père La Chaise and letters from the French priest were found in his possession. The sum of twenty thousand pounds had been offered to him for his continued services to France and for working to bring the Catholic faith to England.

This was one of those unfortunate coincidences. I had no doubt that Coleman had been in the pay of France for many years, for they had their spies everywhere. He was a Catholic, of course, and that was known and was the reason why Titus Oates had named him as one of the suspects.

What luck this was for Titus Oates! In the eyes of the people he was vindicated. He had brought a dangerous spy to justice.

There was something else — and I believe this was less fortuitous — in fact a part of the plot.

It concerned the Justice of the Peace Sir Edmund Berry Godfrey.

It appeared that on Saturday morning he left his home at nine o’clock to go to Marylebone to see one of the church wardens at St. Martin’s in the Fields on parochial business. Later he went to St. Clement Danes, calling at Somerset House. After that no one knew where he had gone, but when he did not return, his servants became alarmed, for he was a man of regular habits.

It was Lady Suffolk who told me what had happened. I think my friends were all growing a little uneasy since Titus Oates had sprung into prominence, for the very fact that the so-called plot was directed against Catholics would mean that I could not escape suspicion. I had had my enemies before, but this was a particularly dangerous one.

It was Friday, I remember, six days after Sir Edmund had last been seen.

Lady Suffolk could not hide her consternation, and I demanded to know what was wrong.

She said: “Your Majesty, they have found Sir Edmund Berry Godfrey.”

“I am glad of that,” I said. “What had happened to him?”

“He is dead, Madam. He had been run through with his own sword.”

“Killed himself?”

She shook her head. “It is believed that the wound was not self-inflicted.”

“But why…?”

“There is great excitement. There are crowds in the streets. They are saying…”

“What are they saying?”

“That he was the one who laid the information before the Privy Council. They are saying it is the papists’ revenge.”

I held onto a table for support. I felt dizzy. It was not enough that Coleman had been proved to be a spy. Now this would be further evidence.

Catholics in this country were in acute danger — not least myself.

THERE WAS TENSION EVERYWHERE. People wanted to know how the Justice of the Peace had been murdered and by whom. I knew a great deal hung on the answer. He it was who had brought the plot to the notice of the Privy Council, which had resulted in the arrest of certain spies — one of whom was Coleman who had been caught red-handed.

And now…what?

Charles himself told me what had happened at the inquest which had been held at White House on Primrose Hill in Hampstead, as it was in that neighborhood that Sir Edmund’s body had been found. The doctors declared that he had not died through the stabbing but had been strangled first. He had died of suffocation. He had not been murdered on Primrose Hill, but his body had been taken there after the deed was done…several days after, probably five. There was money on him so it had not been a crime of robbery.

It was clear that Fate was working in Oates’s favor. First Coleman and now Sir Edmund Berry Godfrey.

For some days I lived in a state of trepidation, wondering what the outcome would be. I knew what rumors were going round the city. People were saying that the murder had clearly been the work of Catholics. It was their revenge on Sir Edmund for putting the case before the Council. Titus Oates was once more the hero of the day. They said that it was now quite clear that in our midst were those who would stop at nothing to bring the country back to the faith it had rejected.

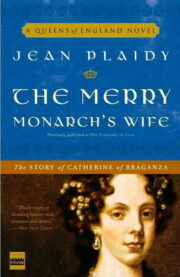

"The Merry Monarch’s Wife" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Merry Monarch’s Wife". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Merry Monarch’s Wife" друзьям в соцсетях.