And so the time was passing. Charles showed little sign of age. He was as vigorous as ever; when he removed his wigs one did see that his black hair was liberally streaked with gray, but when the wig of luxurious curls was on his head he seemed as young as ever.

James was looking for a wife and when Mary Beatrice of Modena was found for him, there was dissatisfaction throughout the country. The English, as ever, were wary of Catholics. I was one — but I think that by this time they had come to realize I was a docile one. But Catholicism allied with barrenness could make a queen very unpopular.

However, the marriage went ahead. Mary Beatrice, a young girl of fifteen, could not have much influence, and in any case James was already too steeped in his religion to be weaned from it even if he did have a Protestant wife.

I was also sad when I heard that the Earl of Clarendon had died abroad. I remembered him so well and wondered if he had felt a twinge of conscience when his daughter Anne died. He had not been very kind to her at a time when she needed kindness. But he had been a good husband…if that meant a faithful one. He was a man of high moral standing, but lacking in kindliness, so different from Charles who would never have turned against his own daughter in her time of need. Clarendon had not always been a friend to me — still I could be saddened by his death.

A certain interest was aroused when workmen, doing repairs in the Tower of London, found the skeletons of two young boys buried under the stairs. These, it seemed without doubt, were the remains of the young princes who had disappeared some two hundred years before — little Edward V and his brother the Duke of York. It was during the reign of Richard III that they disappeared, and it was said that they had been murdered on the orders of King Richard. People talked of the unfortunate boys for a while and then forgot them.

Life went on much as usual. Louise de Keroualle and Nell Gwynne still reigned in Charles’s seraglio, but I had my place and if Charles often preferred the society of his mistresses, there was a growing affection between us. There were times when he came to me, I believe, for quietness and peace.

I began to feel a certain satisfaction in my role. At least I had some place in his life.

But behind the serenity the storm was growing. It was still what many people in England thought of as the Catholic menace. It was the old story: the Queen was Catholic and barren; James, the heir to the throne, was openly Catholic, and now he had married a Catholic wife.

Something was certain to erupt.

I HAD PROMISED ANNE HYDE that I would keep an eye on her daughters, and I was a frequent visitor to Richmond Palace where they were being brought up.

The Duke of York was an indulgent father, as Anne had been another. There was, I have to say, little discipline in the household. Anne, the younger, had taken very little advantage of the tuition which was provided. It was a matter of study if you want to — and Anne clearly did not want to.

Her handwriting was indecipherable and if she were reproved she would say that writing made her eyes tired. She did have an affliction of the eyes which seemed to contract her lids, and it was true that she was short-sighted. So this excuse was accepted, for the Duke had made it clear that above all things he wanted his daughters to be happy. It may be that he remembered his own childhood when, like most of the family, he had been a homeless exile; and I imagined that Henrietta Maria might have been an exacting parent even with James, one of her favorites.

It was always interesting to go to Richmond and on this occasion I wanted to see them, particularly Mary, because I knew of the secret negotiations which were in progress, now we were at peace with Holland, for a marriage between her and Prince William of Orange. Mary was only fifteen, and I could guess how disturbed she would be at the prospect of leaving her comfortable home.

Moreover, from what I knew, William was not the most attractive of young men. He was a Protestant, though, and the country would approve; and it was very necessary to have that approval.

I remembered, some years ago, William had paid a visit to our court. He had probably been about twenty then, for he was twelve years older than Mary. His mother was Charles’s sister Mary, who had been the Princess Royal of England, and his father, the Prince of Orange, had died at the time of young William’s birth, so in his cradle the boy became Prince of Orange.

He must have been amazed by what he discovered at his uncle’s court. Young, inexperienced as he was, he attracted the interest of the courtiers and they decided to amuse themselves at his expense.

I remember the occasion well, for I felt sorry for the young man.

They had made him drunk — a condition which was new to him. They had caroused with him…leading him on to such mischief that he tried to force his way into the quarters of the ladies-in-waiting, and when he met resistance, broke a window and attempted to climb in. The jokers then thought that was enough and took him away. I recall how Charles laughed about his sober nephew’s drunken attempts at depravity.

And this was the young man whom it would be expedient for Mary to marry.

I came to Richmond with some trepidation, for I was sure I should find Mary very apprehensive.

As soon as I arrived I realized that she had heard the rumors.

Everything was much as usual in their apartments. Mary and Anne had always been together, Mary being the more dominant of the two, and they were surrounded by their close friends and attendants.

Their governess was Frances Villiers, daughter of the Earl of Suffolk. I had heard from her how difficult it was to teach Anne.

“Mary is different,” she said. “She is quite interested in learning. Of course, the Duke adores her, and she does not want him to think she is ignorant like her sister. Anne does not care. The only one who can tell her what to do is Sarah Jennings. They are very close friends and you would sometimes think Sarah was the mistress. It is pleasant to see the friendship between all the girls.”

I joined them. Anne was sitting next to Sarah Jennings, a very bright-looking young woman, the kind who would stand out among others…not necessarily because of her looks…but perhaps because of her somewhat imperious manner. I could well believe in her mastery over her lazy mistress.

They rose when I entered and came to do homage to the Queen — Mary first. I felt a pang of anxiety. She was so young and rather pretty with her dark hair and almond-shaped eyes. She had the Stuart look, and she was a sensible girl. I knew that the Duke was passionately devoted to her and indulged her greatly. She could have been spoiled but, to her credit, she was not, and was a very pleasant girl.

“Your Majesty,” she began.

I smiled and took her into my arms.

“Dear Mary,” I said. “You are well, are you?”

“Yes, thank you, Your Majesty, and you?”

“I am well, thank you. And here is Anne.”

Anne looked at me with that rather vague expression which was due to her short-sightedness.

“Anne, my dear, you are well?”

“I thank Your Majesty, yes.”

I smiled at the attendants: Anne Trelawny, Mary’s special friend, and Elizabeth Villiers, Frances’s daughter, and, of course, Sarah Jennings.

They rose and curtsied, then retired so that I was apart with Mary and Anne.

I wished there need not be this ceremony. I would have liked to talk naturally to all the girls. I was particularly interested in Sarah Jennings and Elizabeth Villiers.

“Madam, has the new baby come yet?” asked Mary.

She was referring to the expected child of her stepmother, the new Duchess. Birth was always a rather depressing topic for me. Mary of Modena had already borne three children in the short time since her marriage. The first, a girl, had been named Catherine after me, but had died almost as soon as she was born. There was a son who had died and a daughter Isabel…and now the prospect of another.

“Not yet,” I told them.

“It would be nice to have a little stepbrother,” said Mary. “Though it is not the same as if it were our mother.”

Both she and Anne looked mournful. They had loved their mother and I fancied they both resented their father’s remarriage.

Anne took a sweetmeat from a bowl beside her.

“Oh, Anne,” said Mary with a little laugh. “You should not eat so many of those.”

“I like them,” said Anne.

“She eats them all the time,” Mary told me.

“Do they not spoil your appetite?” I asked.

Anne said they did not. Nibbling sweets was a habit she had acquired from her mother. Anne had become very fat in the last months of her life. I could not forget her lying on her deathbed…searching for the truth…worrying about the future of her girls.

“Sarah will be getting married soon,” said Anne. “John Churchill is always coming here to court her. His family think she is not good enough for him.”

“Sarah will certainly not agree with that, I am sure,” I remarked.

“Sarah is wondering if she is too good for him,” said Mary.

“I am not surprised at that,” I said. “Well, is she going to marry him?”

Anne nodded. “She really wants to. But she is saying…not yet. She thinks they ought to wait.”

I wonder,” said Mary, “what it is like to be married?” There was a faint note of fear in her voice.

“In time you will know,” I told her.

“Yes…a husband will be found for each of us.”

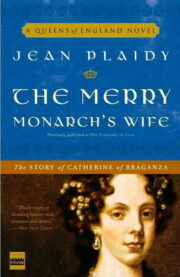

"The Merry Monarch’s Wife" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Merry Monarch’s Wife". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Merry Monarch’s Wife" друзьям в соцсетях.