This, of course, brought home to me afresh my own deficiencies. I was clearly to blame. Barbara Castlemaine had given ample proof of the King’s virility; Nell Gwynne now had two sons; and Louise de Keroualle, who after her initial reticence had become the acknowledged mistress of the King, had just given birth to a son.

So there could be no doubt. I was always on the watch for the suggestion which might arise again, since it had twice before. Many would continue to ask: should not the King free himself from this barren wife?

I had had Charles’s assurance that he would never divorce me, but could one rely on Charles? There was a rhyme, written by the irrepressible Earl of Rochester, which was being circulated throughout the court. Rochester had had the effrontery to pin it on the door of the King’s bedroom. It was:

Here lies our Sovereign Lord the King

Whose word no man relies on

He never said a foolish thing

And never did a wise one.

Charles was the first to appreciate the rhyme. It was amusing, witty and there was some truth in it.

His retort was typical of him. “’Tis true, Rochester,” he said. “But remember my words are my own, my actions my ministers.’”

I quickly learned that Louise de Keroualle was more clever than any of her predecessors, and therefore more dangerous. She was indeed Louis’s spy.

She was possessed of all the graces she had learned at the French court; she was elegant and dignified; I imagined Charles enjoyed mental as well as physical stimulation with her. She was without doubt maîtresse en titre. Nell Gwynne was her great rival, but Nell, of course, was a child of the streets of London: she could amuse; she had wit; and she was very pretty. But Charles was a cultured man and there were times when he wished to be with people of his own kind. Yet I imagined there were occasions when he wanted to escape from Louise to Nell.

From what I knew of the little playactress, she was of a tolerant nature. It must have been a great adventure for her to have attracted the King. She was, I believe, less demanding than any of his mistresses had ever been, and asked only for privileges for her sons. She had two of them now — fine boys and a further reproach to me. And because she did not ask, she did not receive.

She had, though, demanded a title for her eldest son, who was now the Earl of Burford. How she must have laughed to think of herself…little Nelly…fighting for a living, selling her oranges, getting her chance on the stage…and then becoming a favorite mistress of the King, side by side with such as Lady Castlemaine and the Duchess of Portsmouth, as Louise de Keroualle had now become.

There was a story that in the King’s presence she referred to their little son Charles — named after his father — as the “little bastard.”

Charles protested and she flashed back “I call him so because that is what he is. I might as well drop him from this window for who cares for him? Certainly not his father. So I say, poor little bastard.”

It was playacting, of course. They were in the town of Burford at the time and Charles called out dramatically, “Save the Earl of Burford!”

That was good enough for Nell. Her son had a title. He could stand beside the offspring of Barbara Castlemaine and Louise de Keroualle.

There was an undercurrent of unease everywhere. The conversion of the Duke of York was at the root of it. The country was divided. I knew that many prayed that I would have an heir — the King’s legitimate son to be brought up in the Protestant faith. There would be trouble if James came to the throne.

And then…there was Monmouth; and the deeper the resentment against the Duke of York became, the more blatantly Monmouth displayed his Protestantism. It was clear what was in his mind. What he longed for was that the King should declare he had married Lucy Walter. The fact that she would have been completely unsuitable to marry the King was of no importance. Charles had been merely an exile at the time. How simple everything could have been! But much as Charles doted on his son, he was not prepared to lie to that extent for him. Monmouth had his followers and he was very wary of Louise — a Catholic who would surely work against him.

The young Duke sought every way of showing people that the King regarded him as his beloved son, and the rumor about the box containing documents proving Charles’s marriage to Lucy Walter was revived.

“There never was a marriage, so there never were these documents,” Charles declared emphatically, “and therefore they cannot be discovered.”

Monmouth wanted to command the forces which were being sent to Flanders.

Charles told me of this, for he was perplexed.

He said: “How can he? He lacks experience. I know he is popular. He is so good-looking, but that is not enough. He came to me, begging me on his knees to give him the command.”

“You have not done so!” I cried in dismay, knowing his weakness where Monmouth was concerned.

He shook his head. “No…but he was so appealing. He really is a handsome boy…and affectionate. I know that much of his love and devotion is for my crown, but perhaps without that useful ornament, there might be just a little for my plain self. Poor Jemmy. It is not an easy position for him. There is adulation wherever he goes, and he is ambitious, as most of the young are. I sometimes think he might have been happier if he had been a son of one of Lucy’s other lovers.”

“Are you sure he is your son?”

“There is little doubt of it. He is pure Stuart. I see ourselves reflected in him.”

“And what have you decided?”

“I’ve sent for Arlington. He will take care of it. Monmouth will be known as commander, but there will be others to take care of the troops.”

I marvelled at his tolerance toward Monmouth. I often thought of the affair of Sir John Coventry and that poor beadle who had lost his life. Surely those two events should have shown Charles the nature of his beloved son and how dangerous his ambition could become.

Louise was very unpopular with the people. In the first place she was a foreigner and, even more detrimental, a Catholic. I had always been under suspicion because of my religion. It was strange that the English, who were lackadaisical in their attitude toward religion, should have felt this passionate determination not to tolerate a Catholic on the throne.

There were times when it was quite dangerous for Louise to ride out in her carriage, for the mob could be fierce against her.

“Go home, papist,” they shouted at her. “Go back to where you came from.”

It was different with Nell Gwynne. She had a way of charming the people. After all, she was one of them. They would surround her carriage, shouting good wishes, and she sometimes gave a performance of mock-royalty, which amused them and made them cheer her the more.

“Long live Nelly,” they cried. “God bless pretty, witty Nell.”

There was one occasion when she was in a closed carriage and people mistook her for Louise. They gathered round, shouting abuse, and someone threw a stone. Nell let down the window and looked out.

“You are mistaken, good people,” she cried. “This is not the Catholic whore but the Protestant one.”

There was much laughter and cheering, and shouts of “God bless Nelly.”

Nell bowed and smiled and waved her hand in imitation of a languid royal personage, which amused them the more; and, instead of a dangerous situation, it turned out to be a very merry one.

IT OFTEN AMAZED ME, when I looked back on that innocent girl I had been on my arrival in England, that I had been able to accept Charles’s mistress as a matter of course. There could have been only a few faithful husbands at court, or wives for that matter. Licentiousness was the way of life here. I deplored it and sometimes thought how happy I could have been if Charles had loved me as I loved him; but that was not to be and I had had to come to terms with it.

I was grateful to him because he had refused to set me aside. I must be relieved because he had a great deal of kindness in his nature and the rare ability of putting himself in the place of others. He understood my love for him and appreciated it; he understood that Monmouth’s arrogance grew out of his insecurity. There was so much love in Charles and I had long before decided that I would rather accept his mistresses than be without him.

The war with the Dutch gave cause for anxiety. We had our victories but, like many such, they were hollow ones.

There was news that a battle had taken place under the Duke of York at Southwold Bay. Ineffectual as James could be in so many ways, the navy was an obsession with him and he had become a good commander. Against him on that occasion was De Ruyter, the Dutch commander of some renown. It had been a fierce battle and the struggle a desperate one. Many ships were lost and among the casualties was the Earl of Sandwich.

I was saddened, remembering the day he had come to bring me to England, and felt how pointless were those hard-won victories which turned out to be so indecisive.

Charles too was distressed by the death of Sandwich. He sailed to the Nore to meet James who was returning with the fleet. Many of the ships had been severely damaged and the number of wounded appalled him. He was particularly depressed by the latter and gave orders that care for them must be the primary concern.

About a month later he took me down to inspect the ships. Then all signs of battle had been removed and I enjoyed the expedition with him. It was on such occasions that I felt that I truly was the Queen.

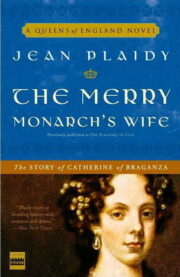

"The Merry Monarch’s Wife" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Merry Monarch’s Wife". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Merry Monarch’s Wife" друзьям в соцсетях.