She said: “He seems to have a preference for Sir William D’Avenant’s players.”

I said: “He always found pleasure in the theater. The reason he has not been there so much of late is because he has had weightier matters on his mind.”

“Well, he is certainly finding D’Avenant’s The Rivals good entertainment.”

I might have known there was some insinuation behind her words. There was one name which I heard mentioned frequently. It was that of a certain Moll Davis.

I asked Lady Suffolk who Moll Davis was.

“Oh, Madam, she is an actress of Sir William D’Avenant’s company.”

“She seems to be attracting a good deal of attention. Is she very good?”

“They say she is very good indeed.”

“Perhaps I should go to see her.”

“It may be, Madam, that you would not care for the play.”

“But since everyone is talking about her…”

“She is a pretty girl…and some people like that.”

She was telling me something.

She went on: “It is her dancing perhaps. She dances a very merry jig.”

Suddenly the truth dawned on me. I heard one of the maids singing a song which sounded like “My lodging is on the cold ground…”

“You don’t sing it like Moll Davis,” said another.

“I’ll swear she doesn’t have to sleep on the cold ground now.”

There was laughter and giggles. “Changed the cold ground for a royal bed, eh?”

So then I knew. I flushed with shame. Why was I always the last to hear?

He was tired of Lady Castlemaine. He would have finished with her altogether, I believed, but for the fact that she would not allow herself to be set aside without making a great noise about it, so I supposed it was easier to let her go on clinging.

I gradually learned that Moll Davis had left the Duke’s Theatre and was set up in a house of her own. She possessed a handsome ring worth six hundred pounds.

Lady Castlemaine was heard to say that the King’s taste had gone from simpering idiots who played making card houses to vulgar actresses who danced jigs.

I was very sad. I thought he had changed a little, grown more serious. But no, nothing had changed. There would always be women…ladies of the court…actresses…it would always be thus.

On reflection, though, it was easier to accept the actresses than the ladies of the court, and when I contemplated what I had suffered through Lady Castlemaine and Frances Stuart, I told myself that I had little to fear from Moll Davis.

THE COUNTRY WAS in a very precarious position and there was a recklessness in the air. We were on the verge of bankruptcy. Rarely could so many misfortunes have occurred in such a short time.

Charles was worried. There were two sides to his nature. People might think him selfish and self-indulgent, but beneath all that insouciance there was a shrewd and clever mind backed by a determination never to go the way his father had gone. People declared that Clarendon had been the author of our ills. They refused to accept the absurdity of this and waited for the Cabal to produce a miracle.

There was an uneasy situation between James, Duke of York, and the Duke of Monmouth. It was obvious that Charles doted on his son. As for myself, I could never look at that handsome young man’s face without being filled with foreboding. He was a constant reminder of what Charles might have had from the right woman.

Monmouth resembled his father in some ways. He was sought after by women because of his looks and position. He was already known as a rake. He was full of high spirits and liked to roam the streets with his rowdy companions causing trouble. Charles was constantly making excuses for him and smoothing over difficulties made by the young man’s conduct.

There was no doubt that Monmouth was attractive and could be charming. I said that he was like the King…not in looks though, except that he was dark. I think he must have inherited his mother’s beauty. He liked to call attention to himself and remind people that he was the King’s son. It was natural, I suppose, particularly as he was not legitimate, but he did want everyone to remember that he was the King’s eldest son.

James, Duke of York, was very wary of him. I liked James because he had been pleasant to me from the first moment of my arrival in England. He was quite unlike Charles except in one respect: he shared the King’s obsession with women and was as unfaithful to Anne as Charles was to me. But there the resemblance ended. James had none of Charles’s grace, though he was a good naval commander. He had proved that, but he had no subtlety and every enterprise of his — apart from naval operations — seemed to go wrong.

There was something alarming in the attitude of James and Monmouth toward each other. I guessed what it was and that I was concerned in this. Monmouth was the King’s beloved son. It was Monmouth who accompanied the King to Newmarket for the races and to Bagshot for the shooting. What if the King, despairing of ever having a child through me, legitimized Monmouth? Then what of James? James must have an eye on the throne, for Charles was no longer very young and was still without legitimate offspring.

Monmouth yearned to be made legitimate and James feared that it might happen. Therefore they were very watchful of each other…and of me, for if I produced a child the matter could no longer concern them so deeply.

When I had discovered that Charles contemplated divorcing me, that he might marry Frances Stuart, I had been deeply shocked and, even though Frances had now married, I had not yet recovered from it.

What was so hard to endure was that Charles had numerous children. Barbara Castlemaine alone had, I believed, six — healthy boys among them. There were others scattered around, so there was no doubt as to whose fault it was that the marriage was unproductive. I felt wretchedly inadequate and never quite sure when Charles might attempt to get rid of me…not only for his own satisfaction but for that of the state.

When James committed some inanity which set the people laughing behind their hands, Charles said to me: “The people are wondering whether they did right to call me back. Cromwell gave them drab lives, telling them that pleasure was sin — and they did not like that. Is it possible though that they might prefer even that to what they are getting now?”

And when I protested that the people loved him, he went on: “They might just tolerate me for my time…but if it is James who comes after…” He shook his head gravely. “I fear for James.” I could see speculation in his eyes. Was he thinking of that other James…Monmouth?

It seemed at that time that manners became even more licentious. Courtiers were blatant in their promiscuity. I supposed they would say they were following the King’s example. Lady Castlemaine’s affairs were the talk of the town. The King was involved with a play actress, Moll Davis. He was turning more and more away from Lady Castlemaine, who retaliated by conducting love affairs with people in all stations of life. She would go to the theater and afterward summon actors to visit her. She made no secret of her amours.

“I always follow the royal example,” she said flippantly.

She was insatiable, it was said. I supposed that had been the reason for the attraction between her and Charles.

Yet he still visited her.

In the streets bawdy songs were sung about the various personalities of the court. Lampoons were passed round and Barbara Castlemaine could not be expected to be left out.

I was shocked to hear someone in the palace singing: “Full forty men a day provided for the whore, Yet like a bitch she wags her tail for more.”

These lines on Barbara were attributed to the Earl of Rochester, who was a great favorite with the King. He was a wild rake, noted for his wit, and he and Charles were often together. He was related to Barbara Castlemaine, and he spared no one in his verses…not even the King.

Buckingham, of course, was in the center of the scene, more outrageous, impulsive and wilder than any. He behaved very badly to his long-suffering wife. I often wondered what Mary Fairfax thought of marriage to a grand duke; I imagined she longed for the dignity of her father’s Puritan home. Buckingham, whose morals could be compared with those of Lady Castlemaine, was quite shamelessly carrying on an amorous intrigue with the Countess of Shrewsbury. He had brought her into his house and expected his wife to accept the presence of his mistress.

It was reported that Mary Fairfax had confronted the Countess, saying there was not room for both of them in the house and she must therefore ask the Countess to leave at once. At which time Buckingham had come upon the scene and declared that she was right. There was not room for the three of them, therefore he had ordered his carriage to conduct Mary to her father’s house.

Such stories, even in the immoral climate of London at that time, were considered by most people to be outrageous.

The Earl of Rochester had abducted the heiress Elizabeth Malet, married her and taken possession of her fortune.

There was a great scandal when the Duke of Buckingham fought a duel with the Earl of Shrewsbury and one of Buckingham’s seconds was killed on the spot and Shrewsbury died from his wounds a few weeks later. Lady Shrewsbury, the cause of the dispute, stood by dressed as a page holding Buckingham’s horse while the duel was in progress.

Buckingham continued to live in blatant adultery with Lady Shrewsbury.

It seemed that however outrageously people behaved, it was acceptable. What could be expected, some of the more serious-minded asked, when the King showed such contempt for moral standards?

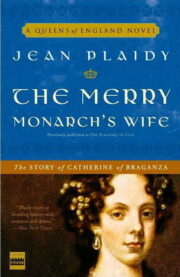

"The Merry Monarch’s Wife" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Merry Monarch’s Wife". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Merry Monarch’s Wife" друзьям в соцсетях.