I had believed that our relationship would strengthen in the years to come and that those women would become less important to him; and I would be there — his friend and faithful wife.

I remembered how he had dismissed poor Edward Montague. I had tried to deceive myself into believing it was out of jealousy. But no. Even though I so much wanted it to be, I could not accept that. Edward had gone solely because of the insinuations of Buckingham.

How deep was his passion for Frances Stuart? I asked myself. How strong his regard for me? I knew him well enough to realize that he would be upset to cause me pain; and to divorce me would certainly do that.

And the people? There would be some who would frown at divorce, but I was after all a foreigner and they did not like foreigners. They wanted to see an heir to the throne and they had convinced themselves that I could not provide it. Frances Stuart was beautiful; she would grace all occasions and it would seem that she had an excellent chance of giving the country an heir.

I saw little of Charles then. He was more immersed in state matters than usual. The aftermath of the fire, with the rebuilding, rehabilitation of the people, the progress of the war, the fact that enemies were taking advantage of the impoverished state of the country, all demanded his constant attention as well as that of his ministers.

It was reasonable enough, but to my tortured imagination it seemed that he avoided me, which a man of his temperament would do if he were contemplating getting rid of his wife.

This was one of the most unhappy periods of my life. Each day the possibility of Charles seeking a divorce seemed more plausible.

And then Edward Hyde, Earl of Clarendon, came to see me.

He was in an uneasy state of mind, for his own future was precarious.

He was a great statesman and a man of letters. He had written several histories of his times among other things; he was learned and clever. Charles, who had known him for many years, thought very highly of his erudition. He was a man of principles and often reproved Charles for his mode of life. Charles did not resent this. He would say it was true and Clarendon was right and that he should reform his ways. But Clarendon was asking more than Charles was prepared to give, so, in characteristic manner, the King shrugged his shoulders and implied that the people had asked him to come back and they must accept what they got.

Clarendon, I often thought, was uneasy in this atmosphere of frivolity which surrounded the court; and, being entirely different himself from most of the others, he had many enemies. He had originally been intended for the Church, which might have suited him very well, but on the death of his two older brothers, he became his father’s heir; and when he joined the Middle Temple at that time his uncle, Sir Nicholas Hyde, was the Chief Justice, so he had a good chance of advancement. However, he decided he would not pursue a career in the law as he wanted to devote himself to writing. This he had done. Charles had once said it was rare that a man who owed his fame to writing and speaking should have a prominent place in the government.

Well, Clarendon was an unusual man.

At this time he must have been in his late fifties, but, apart from the gout, he was in good condition.

I sensed as soon as he arrived that he found the matter which had brought him somewhat delicate and he began by saying that his daughter had thought that we must talk with the utmost frankness.

I said: “I should prefer that.”

The color was high in his habitually ruddy cheeks, and I imagined he was choosing his words carefully.

“I have come to Your Majesty in this matter of the King and Mistress Stuart,” he said.

“Yes?” I prompted.

“It seems that the King is greatly taken with the lady and…has certain plans for her.”

I said: “He has had plans for her for a long time, my Lord Clarendon, but they have come to nothing because of the virtue of the lady.”

“Exactly so.”

“The Duchess of York has spoken to me of this matter,” I said.

I guessed then that Anne had come on her father’s advice.

Clarendon went on: “I am sure Your Majesty will agree with me that it would be well for everyone concerned if the lady had a husband.” He was looking at me intently, as though assessing me. We had been in a somewhat similar situation when he had warned me about Lady Castlemaine and suggested how I should act. Then he had told me that I should accept her, and had been shocked when I did.

This, of course, was different. Then we had been talking of the King’s mistress…now we were speaking of one who might become his Queen.

“The King has had a most unhappy time,” he said. “The plague…the fire…this war.” He lifted his hands. “He was more disturbed than he would have people know.”

I guessed what was in his mind. The King was depressed by all his difficulties; he was frustrated by Frances’s refusals; in such circumstances he might be tempted to do something rash.

He cleared his throat. “Your Majesty, Miss Stuart should be married as soon as possible.”

I stared at him in horror, and he hastily added: “To one of her admirers, and so prevent this situation from worsening.”

“Is she prepared to marry?”

“She seems to be on very good terms with her cousin, that other Charles, the Duke of Richmond and Lennox.”

I knew the man. He was of the Stuart family, as Frances herself was. He must have been about ten or eleven years older than she was.

“Is he eager to marry her?” I asked.

Clarendon raised his shoulders to imply who was not eager to marry Frances Stuart?

“He is free to marry,” said Clarendon.

“And Frances Stuart?”

He hesitated. “It occurred to me…well…she is a lady of your bedchamber…a word from the Queen…. She could be reminded of the pitfalls about her. I am sure she would understand.”

“You are suggesting that I should talk to her, that I should tell her she should marry Richmond?”

“She would listen to Your Majesty’s advice. She is a very simple girl. She needs advice. She could find herself in a difficult situation which she would not be able to handle.”

“Talk to her? I…?”

“Who but the Queen? Perhaps Your Majesty would think about the matter. But I do believe that some prompt action is necessary.”

“I understand,” I told him.

“I knew Your Majesty would. The girl should be settled. That is most important.”

He smiled and took his leave.

When he had gone I felt deeply shocked. He had talked in innuendoes but I knew what was behind it.

It was true that Charles was contemplating divorcing me and marrying Frances Stuart. It might well be that Archbishop Sheldon was already working out a means of getting a divorce for the King on the grounds of my infertility.

I was frightened. Stretching out before me was a dreary future. I should be sent away. I should never see him again. And, strange as it might seem, I would rather be near him enduring jealousy and uncertainty than be away from him.

I thought of going back to Portugal: the emptiness of the palace without my mother, the quarrels between my brothers, myself sitting day after day with my attendants, stitching…reading…listening to music; perhaps waiting for the Spaniards to attack us.

I could not endure it.

Clarendon was seriously concerned. He would do everything he could to stop the divorce. He had arranged my marriage, and my downfall would be his. He would be making comparisons, as all would be at this time, and thinking of the fate of Cardinal Wolsey. And Thomas Cromwell was another who had arranged an unsatisfactory marriage for his King. Then it might be that Clarendon wanted the King’s marriage to be unfruitful to make the way clear for his grandchildren.

For whatever reason, he did not want a divorce for the King, so he and I were allies. He was ready to fight for his position and that of his grandchildren; and I would fight for my future.

I was thinking what I would say to Frances Stuart.

I DID NOT HAVE TO SAY IT. I had forgotten Lady Castlemaine’s part in all this. How that woman always seemed to be in the forefront!

I had not given much thought to what she would be feeling about these rumors until then.

She hated Frances. She knew that if Frances Stuart had given way that would have been the end of Barbara Castlemaine; she was lingering on as second best, only holding her position because it was rejected by Frances. The thought of her rival actually sharing the throne must have infuriated her.

She had always made it her affair to know what was going on. She had her spies everywhere. Her Mrs. Sarah would be on good terms with Frances’s servants; and if Frances ever turned from her virtuous path, one could be sure that it would reach Barbara’s ears before long.

It was the day after Clarendon had spoken to me. There was tension in the air, tittering and sibilant whispers in corners which told me that something had happened.

I learned of it from Lettice, though she was rather reluctant to tell it, for the reason that Charles played a part in it.

Frances was not on duty and I asked where she was. She was not feeling well, I was told.

“What ails her?” I wanted to know.

Lettice looked at Lady Suffolk, then Lettice burst out: “She was somewhat upset last night, Your Majesty.”

“Why was that?”

There was silence.

“I know something has happened,” I said. “I want to know what. Is there some secret, some conspiracy?”

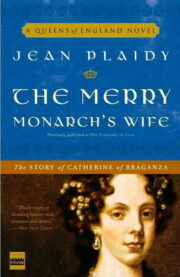

"The Merry Monarch’s Wife" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Merry Monarch’s Wife". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Merry Monarch’s Wife" друзьям в соцсетях.