“You dare to talk to me like that,” he repeated. “Go and do not return until I send for you.”

She had turned white with rage. I had known for some time that if Frances Stuart responded to his advances, Lady Castlemaine’s days would be over.

She said: “I shall go. I do not remain where I am not wanted. But you have not heard the end of this. I shall publish your letters.”

I was amazed at her impertinence. She forgot she was talking to the King. Of course, theirs had been a long and intimate relationship and he had always given way to her when she flew into a temper.

She had forgotten that her hold on him depended on the surrender of Frances Stuart; she must have been furious that no woman had impressed him so much as that foolish girl — not even herself, with all the fury of a virago and the magnificence of a mythical goddess.

She suddenly seemed to realize that he meant what he said. She turned from him and flounced out of the room.

Charles was perfectly calm. He behaved as though nothing unusual had happened.

I was exultant. Surely this must mean the end of Lady Castlemaine.

For a few days my hopes were high. Then she came to the Cockpit to collect her belongings. There were many gifts from the King among them and she asked if he would advise her as to the disposal of them.

It was an excuse to see him. He must have known this as well as any. But he went to the Cockpit to see her.

What happened when he was there, one can only guess. I suppose she exercised that overwhelming sensuality, of which she had an abundance to match his own. This must have resulted in an encounter which made them realize that, although the King’s affection had been strained to breaking point, the attraction was as potent as ever; and while he failed to receive the satisfaction he craved from Frances Stuart, there was still a place for Barbara Castlemaine in his life.

So she did not leave court after all and she and the King were friends again, though even she must have realized that her hold on him had become somewhat tenuous.

THAT WAS A GLOOMY SUMMER. True, there was no return of the plague, but there was deep anxiety throughout the court. We were at war and the whole of Europe was turning against us. My fears about what might be happening in Portugal were overshadowed by the reality of what was taking place in England. France and Denmark were against us. Charles was particularly depressed by the deterioration of his friendly relationship with Louis XIV. He complained continually of having to beg for money. The effects of the plague had been more devastating than had at first been realized.

It was six years since the Restoration and people might be asking if life had not been better under Cromwell.

There were rumors that certain Roundheads were on the continent conspiring how to oust the monarchy and bring back the protectorate. They were indeed anxious days, and although Charles was outwardly serene, he was a very worried man.

In July I went to Tunbridge Wells, for I had not yet recovered fully from my miscarriage.

Since my earlier visit the place had become fashionable. There was a simplicity about it which I found appealing, and to be there with a few trusted friends was agreeable. We would all gather together round the wells during the morning while we drank the beneficial waters. If the evenings were warm we would sit in the bowling green, and there would be dancing on the smooth turf, which all declared was better than any ballroom. I found great serenity there.

In the afternoons a few ladies would assemble in my rooms, which were not large for there was no grand palace in the town and our lodgings were comparatively humble. We would drink tea, for I had brought this custom with me from Portugal. For a short time people had thought the beverage very strange, but they were soon aware of the pleasure of taking that soothing drink, and my ladies quickly became as ardent tea drinkers as I myself. Indeed the custom was spreading all over the country.

We were passing out of the summer, and after a stay of a few weeks we reluctantly left Tunbridge Wells for London.

I SHALL NEVER FORGET — nor will the rest of England — that night in September.

It began in the early morning of the second day of the month. The wind had been fierce all through the previous night and this played a large part in what happened.

The King’s baker — a Mr. Farryner, I believe — lived in Pudding Lane where his kitchen would naturally be stored with wood faggots which would be needed for the baking of his bread. No one was sure how it started, but in a few seconds the house was on fire. It might have been possible to extinguish this, but the house was made of wood and the wind blowing so gustily that in a matter of minutes the fire was out of control to such an extent that, before any action could be taken, the whole of Pudding Lane was ablaze.

We were all awakened, and as we rose from our beds, we saw a strange light in the sky. The wind was sending hot ashes swirling through the air so that they descended on more buildings, causing more fires. People were panic-stricken. There was one aim: to get away from the fire. The river was crowded with crafts of all descriptions and crowds were piling their belongings into these.

Charles was out in the streets. The Duke of York, who was at Whitehall on some navy business, was with him. Everything was forgotten in the need to stamp out the fire.

“The whole of London will be burned down if nothing is done,” cried Lady Suffolk. “If only that dreadful wind would drop.”

Donna Maria shook her head. She could smell the acrid smell, though she could see very little. She said: “God is showing his anger to this wicked city. First he sent a plague; now he sends a fire. It is Sodom and Gomorrah all over again.”

“Wicked things have gone on in all countries, Maria,” I reminded her.

She would not accept that; and I think there were others in England who believed that we were suffering from Divine Wrath. It was significant, they said. The plague and then the fire. The licentious manners of the court, following the example set by the King, outstripped even those of that notorious den of iniquity, the court of France.

During that fearful day news kept coming to Whitehall. Houses near London Bridge were on fire; entire streets were ablaze. There was a glow in the sky and the heat from the fire was so fierce that it was dangerous to venture too near.

The Secretary of the Admiralty came to Whitehall to see the King on urgent business. Charles received him at once. Samuel Pepys was clearly overwhelmed to be in the King’s company, but at the same time there was a sense of great urgency about him.

The King left at once with Mr. Pepys and the Duke of York. Charles told me afterward what had happened. London was in danger of being completely annihilated. Fires were springing up everywhere. It was as though some fire-breathing dragon had taken possession of the city. Fleet Street and the Old Bailey, Newgate, Ludgate Hill and St. Paul’s were all ablaze. The cries of the people mingled with crackling burning wood; there were loud explosions as houses collapsed; the flames were stretching up to the sky and the burning heat was almost unbearable.

There was only one way of saving London: to blow up houses so that when the fire reached them there was nothing for it to consume and it could not spread.

Charles was out there directing operations with his brother James. The fact that they were there gave the people hope. Orders, which had been given by the Mayor, had not been obeyed, but when given by the King they could not be ignored.

It was a mercy that this terrible situation lasted only a few days. Indeed, had it lasted longer, the whole city of London would have been destroyed. And how right was the strategy of blowing up the houses, so making gaps which the fire could not bridge.

Charles worked indefatigably, and I am sure that to see their King riding through the streets, wigless, coatless, face blackened by smoke, ordering the blowing up of buildings, working harder than any, changed people’s opinions of him. There indeed was truly a king. They were all fighting the battle against the deadly fire and because of the inspiration given by the King they knew they were going to defeat that destructive monster.

Charles talked afterward of the horror and the wonder of it — to see fire, the master, flaring, raging, triumphantly licking the buildings with relish before consuming them…the air full of smoke which, when the sun came up, gave a rosy glow to everything, making it the color of blood.

When the fire died down, the doleful task of assessing the damage and giving succor to the homeless began.

It was a great relief to find that only six people had died in the fire. We had feared there would be far more. However, over seven million pounds’ worth of damage had been done. But I think the calamities of the plague and the fire — and in particular the latter — had shown the people that Charles could rise to the stature of a great king when the occasion demanded it.

I BEGAN TO UNDERSTAND CHARLES a little better. Beneath that merry insouciance there was a seriousness and when it was touched it could reveal unsuspected strengths of character.

Having put an end to the fire, we learned that the Cathedral of St. Paul’s was completely destroyed, with eighty churches; so were the Guild Hall and the Royal Exchange among many other buildings. Over thirty thousand houses and four hundred streets were completely finished. It was reckoned that the damage extended over four hundred and thirty-six acres; and two-thirds of the city was destroyed.

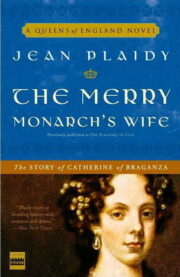

"The Merry Monarch’s Wife" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Merry Monarch’s Wife". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Merry Monarch’s Wife" друзьям в соцсетях.