On one occasion Charles talked to me.

“I do not like the situation,” he said. “I am afraid there may be war. War is senseless. I have had my fill of it. Odds fish, I never want to see a war again as long as I live.”

It was inevitable that it should happen. We were at war with Holland. The fleet was to leave with the Duke of York in charge, and Charles was going to Chatham to see it set out. I begged to be allowed to accompany him and was delighted when he agreed that I should.

It was a great occasion, though a solemn one. Queen Henrietta Maria joined us there and I was pleased when she greeted me with the utmost warmth and told me how pleased she was that Lady Castlemaine was not with us on this occasion.

“I cannot understand why Charles keeps that woman about him,” she said. “One would have thought he had had enough of her by this time. And that Stuart girl? What of her?”

I could talk easily to my mother-in-law, so I told her that Frances Stuart was still holding back, and that the King remained deeply enamored of her though he still very often supped with Lady Castlemaine.

“It is trying,” she said. “It is a pity Charles does not take after his father. He was always such a faithful husband. But I lost him…Charles will never go the way he did. Charles has too much respect for his head. He will keep it where it belongs. But I wish his heart was not so susceptible. And there is this war now…and England is not very friendly with the French either…or the Spaniards. Well, they are the natural enemies.

“I pray this Dutch matter will soon be over and you, my dear, will soon give birth to the heir to the throne.”

“I was unfortunate…”

“My heart bleeds for you, chérie. And no other in sight? Some breed easily. Others cannot. This is the story of history. It is littered with queens who could not have any children and those who had too many. How perverse life is! But you must have a child, my dear. That will make all the difference.”

“I know.”

“I pray for it.”

It was good to be with her. She stood between Charles and me and shared our pride as the newly launched Loyal London sailed away.

THE WINTER WAS BITTERLY COLD — one of the worst people remembered. We were all looking forward to the spring and victory over the Dutch; but with the coming of that beautiful season, tragedy struck.

Earlier in the year, people had been amazed, and not a little alarmed, because a strange spectacle had been seen in the sky. It appeared at certain times and was like a misty star with a bright tail. Charles was very interested in the stars and would watch for it every night. I used to sit with him and look at this strange object. I think he was rather pleased by my interest. It was not the sort of phenomenon which would interest Lady Castlemaine or the fair Stuart.

Some said it was an evil omen and recalled a similar display in the sky in the year 1066 — the year of the Norman Conquest.

We heard that in some parts of the country there had been a certain disease which was easily passed from one person to another and few who had the misfortune to fall victim of it survived.

I remember the day well. It was April. The weather was beginning to get warm. A man had collapsed in Cheapside and when people approached him they saw that he was shivering and delirious. He had opened his shirt and there on his chest was the dreaded spot…the macula which was a sign that the victim was suffering from the plague.

He was dead. Others were found. They had collapsed in the streets before they could reach shelter.

It soon became clear that the plague had come to London.

It spread with alarming rapidity. There was great consternation and a hasty meeting of Parliament. Everyone in the city was in danger, and drastic measures were needed.

It was decided that the King and the court must leave, for it would be disastrous if the King should become a victim. The country was in a state of uncertainty. We were at war with the Dutch; but the first importance was the health of the citizens.

Charles was no coward. He said he would stay with the people, but the folly of such a sacrifice was pressed upon him. The Duke of York was engaged with the navy; he must of necessity be in a certain danger, so the King must protect himself.

We left London for Salisbury. The Duke of Albermarle remained in London to look after affairs there with Archbishop Sheldon. Both these men proved to be magnificent and I was sure did a great deal to prevent the epidemic becoming more terrible than it was.

Charles was very unhappy at that time. I had never known him to be so serious. He felt deeply disturbed because he was not in London and he had news of what was happening there brought to him every day.

The weather was sweltering hot during that June, July and August and people were dying by the hundreds in the capital.

The Duke of Albermarle had acted quickly and firmly. He reported what he was doing and Charles said he could not have been a better man for the task. The greatest need was to stop the disease spreading. Any house where one of the inmates had contracted the disease must immediately be marked with a red cross and the words “Lord Have Mercy upon us” painted below the cross; and if any of the inmates left that house before a month had elapsed since a victim had died, that would be breaking the law.

Charles and I were closer together during this period. He had little desire to sup with his friends and make merry. He talked seriously of what this would mean.

Firstly we must discover what caused the disease. That it had been brought into England from some other country seemed certain. It was so infectious that it spread with rapidity, which was alarming, and we had to find the cause.

Meanwhile London was like a ghost city. Grass was growing among the cobbles of the streets, for few walked in them now. During the night the death cart roamed through the streets, its dismal bell tinkling in the stillness.

“Bring out your dead,” called the crier; and the cart was filled with bodies.

There was no time to bury the corpses ceremonially. Pits had been dug outside the city and into these the bodies were piled.

There were some very noble and selfless men in London at that time. Archbishop Sheldon was one; another was the Reverend Thomas Vincent. There were others — men of religion who went into stricken houses and gave comfort to the sufferers. It was surprising that they emerged unscathed. I believe their faith preserved them.

There were stories of people who behaved with somewhat less heroism; there were some who deserted wives, husbands and even children to escape infection. Thus many victims were left alone to die.

We were cheered by news of the Duke of York’s victory over the Dutch at Harwich.

Charles told me that the English had taken eighteen of the enemy’s ships and destroyed fourteen more.

“And what were our losses?” I asked.

“The comparison is trifling. We lost only one ship. Alas, several of our men were lost, but few in comparison with the seven thousand they did. And we lost two admirals; the Earls of Falmouth and Marlborough and Portland have also gone. These things must be.”

“Is it going to shorten the war?”

Charles was dubious. “At least,” he said, “it is a turn in our fortunes, and people will cease to brood on the evil warnings of the comet.”

He looked at me quizzically and went on: “You might be interested to know that your one-time Master of Horse, Edward Montague, has joined the navy…under Sandwich.”

“The navy?”

“Well, we have need of all the men we can muster.”

“But he loved horses.”

“Poor Edward. I fear he was deeply hurt by his dismissal.”

“Maybe when he returns…”

Charles gave me another of those intent looks. “Who can say what will happen when the war is over?”

I THOUGHT OF EDWARD MONTAGUE a good deal. I had not realized before that he really had cared for me. I had been too innocent to recognize the signs. I remembered his concern for me, his compassion and his sympathy. The way his eyes would shine when I appeared. Perhaps those were the signs of love which others had noticed.

He must have been very unhappy when he was dismissed, and that dismissal was instant so there was no time to tell me what had taken place.

And he had joined the navy. That would have been easy for him as the admiral, the Earl of Sandwich, was related to him.

I missed him more than I had believed possible. I suppose when one’s husband so blatantly prefers other women there is great comfort in the attentions of someone else — particularly if he is a serious man, not given to light-hearted flirtations, a man who clearly disapproves of the licentiousness of the court, a man of charm and dignity.

I should never have taken a lover, of course, and I am sure Edward Montague would never have indulged in an illicit affair; but he had been there, he had cared for me, and that had meant a great deal to me.

They were melancholy days. The King was worried about the money which was needed to pursue the war. There was bad news from London where thousands were dying every week.

An attempt had been made at Bergen by the Earl of Sandwich to capture a fleet of Dutch ships which were sheltering in the harbour there. The action had been one of complete disaster for the English and there were many casualties. One of them was Edward Montague.

It was a great shock to hear of his death. I had so many memories of him. I thought how strange fate was. But for those people who had provoked a scandal about him, he would have been with me still.

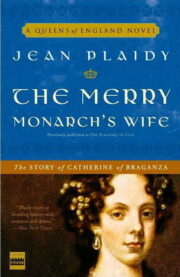

"The Merry Monarch’s Wife" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Merry Monarch’s Wife". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Merry Monarch’s Wife" друзьям в соцсетях.