THERE WAS MORE GOOD NEWS.

I believe my letter to the Pope had had its effect. He had understood the implication that I was going to do all I could to bring Charles to the faith. Perhaps he knew that James was already a secret Catholic. Henrietta Maria knew it and she was scarcely the most discreet of women.

I had heard from Charles that her inability to keep a secret could have been in a measure responsible for his father’s downfall. It would have been the last thing she intended; she would have died for her husband, instead she had talked to one of her ladies on that occasion when the five Members of Parliament, headed by John Pym, were to be arrested and taken to the Tower. But, having been warned, the men escaped in time to carry on the war against the King. It seemed to me very likely that somehow, unwittingly, Henrietta Maria would have let out the news of James’s conversion. On this occasion, it could have worked for good, because it might be surmised that if one brother had turned, why not the other? And as Charles’s wife, I was in a position to influence him, so might the Pope think.

In any event, the Pope had heeded my letter, for to our great joy, he accepted Portugal as a sovereign state and my brother Alfonso as its king.

To add to my happiness, I believed that I was at last pregnant.

I was very excited. Everything would be worthwhile now. A child of my own! Our son and heir! Charles was with me more often now. We walked together in the Park. People cheered us. Although they were amused by the King’s amours, at heart they preferred to see me with him rather than Lady Castlemaine. He was seeing less of her — but I did not think that was because of his preference for my society, so much as his preoccupation with Frances Stuart.

Frances went on in her guileless way, screaming with delight when her opponents’ houses of cards toppled to the ground, making them all join in a game of Blindman’s Bluff. It was so ridiculous. I could not imagine why they did it — except that she was exquisitely beautiful. I had heard it said that she was the only woman at court who had ever outshone Lady Castlemaine in beauty. And she was so different. Everything the Lady was, Frances was the opposite. Simplicity against sophistication; innocence against experience; purity against blatant sexuality; and one might say stupidity against the utmost guile.

My doctors thought the water of Tunbridge Wells would be good for me, but when I was making arrangements for a journey there, I was informed by my almoner that there were insufficient funds for the journey.

On making inquiries, I learned that, although according to the contract which had been drawn up at the time of my marriage, I had been promised forty thousand pounds for my household expenses, I had received no more than four hundred.

When I mentioned this to Charles he was evasive. He never cared to discuss money with me. He even hinted that I could scarcely complain about the deficiency in my income when I considered what had happened to my dowry. I thought I should never be allowed to forget that spice and sugar which my mother had sent in place of the money.

However, after a great deal of discussion, the expenses for the journey to Tunbridge Wells were raised and I was able to go.

I was delighted when the King announced his intention of coming with me — but perhaps that was because Frances Stuart was a member of my household.

Our journey to Tunbridge Wells was a pleasant one. We were cheered in the towns and villages through which we passed and I felt that the people of England were becoming reconciled to me — doubtless because they had heard of my condition.

I was glad the King’s devotion to Lady Castlemaine was waning at last. It was true I had to accept her rival, but I did not feel the same animosity toward Frances Stuart. She was always extremely humble in my presence and was not a very formidable rival; for I firmly believed that when and if she did succumb to the King’s passion, he would soon tire of her. Her empty-headedness must surely bore him, for I doubted even beauty such as hers could hold a man of his culture and intelligence for long.

She did not seem to grow up at all. She went on delighting in her games and I never failed to be astonished that her admirers could stand by applauding when her card house was the winner.

Charles was very interested in the chalybeate springs which brought many people to Tunbridge Wells. The spring contained iron salts which were beneficial to the health. Charles had always been intrigued by such cures, and had his own gardens where he cultivated and experimented with herbs. He was very considerate about my health, and I began to feel happier than I had for some time. I was longing for the day when my child should be born. I hoped it would be a boy for the nation’s sake, but I knew that, for myself, whatever sex it was, it would delight me. It would be wonderful to have a daughter, but of course, I must pray for the son everyone wanted.

Sometimes Charles and I talked about the child. He would love it, I knew. His affection for James Crofts — the Duke of Monmouth now — showed that.

He had other children too. Lady Castlemaine had several which she swore were his, but in view of the life she led, that was open to doubt: she was the sort of woman who would claim royal parentage for every child she bore.

I tried to stop myself thinking of her. I must be grateful for my good fortune. I was pregnant; Charles was kind and tender; the rapacious Castlemaine was in the shadows and I believed I had little to fear from silly Frances Stuart.

So, if life was not perfect, at least it was good; and I must enjoy it.

So I remember Tunbridge Wells with pleasure.

We could not stay indefinitely, of course; and the court moved to Bath. James, Duke of York, with his Duchess traveled with us; and among the company was the Duke of Buckingham, a man of whom I was very wary. He was never far from the center of events. He was an admirer of Frances Stuart, and I was sure he was hoping to seduce her before the King succeeded in doing so.

I wished him success, but Frances seemed to have a gift for holding these men at bay and at the same time keeping them spellbound. She did it effortlessly and was consistent in her refusal of them. It would have to be marriage or nothing for Frances. She did not actually say that, but it was implied — and, of course, neither the King nor Buckingham could offer that.

Buckingham had in the beginning been an ardent Royalist, yet oddly enough had married the daughter of one of the Parliamentary leaders — General Fairfax. It was a most incongruous marriage.

Buckingham was an adventurer by nature; he was reckless in the extreme and would throw himself into any wild scheme for the excitement of it. A man of poor judgement, I would say. On the other hand, he was extremely handsome, erudite and charming — the sort of man who could be outstanding in any company. And…he would be ruthless. That was why I felt I had to be watchful of him.

Charles should have been too. He had some knowledge of Buckingham’s methods. The Duke had been one of those who, before the Restoration, had doubted that it would ever take place; and, weary of exile, he had secretly returned to England and had a meeting with one of Cromwell’s men as to the possibility of his estates being restored to him if he came back to England ready to accept Cromwell’s rule. He had previously quarrelled with Charles, when he had contrived to marry the Princess of Orange, a scheme which had been indignantly prevented by the royal family. So no doubt he thought he had little to lose.

Cromwell was too shrewd to accept such a man’s word unquestioningly, and there again Buckingham showed his recklessness in returning to England without the Protector’s consent; so, to consolidate his position, he married General Fairfax’s daughter, Mary, who had fallen madly in love with him.

It was only Fairfax’s influence which saved Buckingham when eventually his recklessness resulted in a spell in the Tower of London.

When the Restoration came, he managed to win Charles’s forgiveness, for Charles found it difficult to bear grudges, and he was amused by Buckingham, who was the kind of man he liked to have about him. So Buckingham became a Gentleman of the King’s Bedchamber, and had the honor of carrying the orb at Charles’s coronation.

It was odd to see such a man as Buckingham leaning over Frances Stuart, cheering her on as she built up her card houses with breathless intensity.

Lady Castlemaine, who, before her marriage to Roger Palmer, had been Barbara Villiers, was related to the Duke. The fact made me doubly wary of him.

After we left Tunbridge Wells, we had a pleasant stay in Bath, Bristol and Oxford, and wherever we went there were demonstrations of the people’s affection for Charles and their acceptance of me; and I reminded myself that I had a good deal to be thankful for. My country was more secure than it had been for many years; the King’s liaison with the evil Castlemaine was coming to an end: and soon I should have my child.

And so we returned to Whitehall.

I WAS DISAPPOINTED that Charles was not with me on the first night of our return to Whitehall. I supposed that he had some business to attend to after the time we had spent away. I saw him during the following day, but briefly, and again that night he was absent.

The next morning I heard the ladies laughing together. Something had evidently happened which was highly amusing.

It was later that afternoon when Lady Ormonde was with me and I said to her: “Something seems to be amusing people today.”

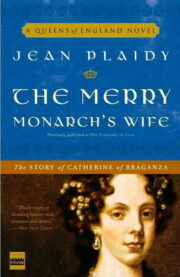

"The Merry Monarch’s Wife" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Merry Monarch’s Wife". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Merry Monarch’s Wife" друзьям в соцсетях.