“You must not blame yourself,” I said.

“I wonder. When we get old, we look back…our lives become overshadowed by memories of the past. But no matter how much one weeps, tears will not wash it out.”

“I am making you sad.”

“No, chérie, you make me happy. You are the wife I would have chosen for Charles. He is fond of you, I know.”

“But fonder of Lady Castlemaine.”

“No. No. That is a sort of fever, I know. I was brought up at the court of Henri Quatre. I know how my father felt toward the myriads of women who surrounded him. They were necessary to him, but it was not deep love. It is a surrender to the irresistible passion of the moment. Understand that and you will have nothing to fear. The crown is yours. You are the King’s wife. These women can do you no harm. Stand firm and remember that…and you have won the battle. You will be the Queen when they are forgotten.”

“How wonderful it has been for me to be with you.”

“For me too, my dear. I came to see you, and I have not been disappointed.”

WE HAD LEFT HAMPTON COURT for Whitehall, that palace which for Charles must hold some very tragic memories, for it was there, before the banqueting hall, that his father had been cruelly murdered.

Whitehall was a fine building. Its gatehouse, made of small square stones, glazed and tessellated, was most impressive. It had been a royal palace ever since Cardinal Wolsey had presented it to Henry VIII, hoping to soften that despotic monarch’s heart toward him for a little longer before he met his inevitable fate. It had been changed since then and, because some of the buildings which had been added were in white stone, it was called Whitehall.

I could not be as happy there as I had been at Hampton Court, where I had gone in blissful ignorance with my romantic dreams.

I had come a long way since then.

I saw a great deal of Lady Castlemaine, who was frequently at court. I used to watch Charles walking with her or sitting beside her at the gaming tables. Everyone was aware of his passion for her.

There had been one concession, though. She did not live as close to me as she might have done. Instead she had her apartments in what was known as the Cockpit, which was a part of the palace, though not exactly of it, for coming out of the palace one had to cross the road to reach it. It was situated next to the tennis courts and bowling green; and as there was cockfighting there, it took its name from this.

Queen Henrietta Maria was now installed at Somerset House.

The Queen’s friendship had cheered me considerably, and I think Charles was delighted to see us getting on so well together.

It was necessary that I should be present on every occasion of importance, and as there were many such, for numerous entertainments were devised for the pleasure of the Queen Mother, I was constantly in his company. No one would have believed that there was a rift between us, but it was still there, and I supposed would be until I received Lady Castlemaine into my bedchamber.

Both Maria and Elvira had been ill and had absented themselves on many occasions for this reason. Maria was getting feeble; her failing eyesight inconvenienced and disturbed her more than anything else; but she was deeply upset by the manner in which I had been treated.

In spite of the language problems, Maria and Elvira had managed to pick up what was happening in the Castlemaine affair and were incensed by it. Together they talked of the dishonor and insult to their Infanta, and had been on the point of writing to my mother. I had prevented their doing this only by forbidding it. Naturally I did not want my mother to know. She had been adamant about my refusing to receive Lady Castlemaine; and that was exactly what I was doing. I could not return to Portugal, and if I were truthful, I must say I did not want to.

The talk with the Queen Mother had brought me comfort, and I had faced the fact that seeing Charles now and then was at least better than not seeing him at all.

Lady Castlemaine was always prominent at the functions, of course. She was the sort of person who had only to be at a gathering to be the most outstanding person there. She was always sumptuously dressed. She had some valuable jewelry — presents from the King, I imagined — her gowns were always more daringly cut than those of others; her magnificent hair was dressed to advantage on every occasion. She wore the most elegant feathered hats; and, hating her as I did, I had to admit she was splendid and the most handsome woman at court.

One day I noticed a young man in attendance on her. He was scarcely more than a boy. I supposed he was about fifteen…perhaps even younger than that. He was exceptionally handsome, tall and dark, with an unmistakable air of assurance. Lady Castlemaine obviously thought highly of him. She was quite coquettish with him; and he seemed to enjoy this.

Several people were with them, and they all seemed to be making much of the boy.

A few days later I saw him again. We were at Somerset House, visiting the Queen Mother, and he was still in the company of Lady Castlemaine. I thought he must be some protégé of hers.

I said to Donna Maria, who had recovered from her illness sufficiently to be with me: “Who is the young man over there?”

She peered ahead, and it was brought home to me how quickly she was losing her sight. Poor Donna Maria, she was trying to hide how blind she was becoming. I turned to one of the women and said: “I should like to speak to the young man who is over there. Do you know who he is?”

“I believe him to be Mr. James Crofts, Your Majesty,” said Lettice Ormonde, one of the women who had joined my service. “It is said that he has been long in France and has recently returned to England.”

“He seems to be very popular. He has the dignity of a man though he can be little more than a boy.”

Lettice Ormonde made her way to the group of which the young man was a part. She spoke to him. I heard Lady Castlemaine laugh and give the boy a little push. He looked slightly embarrassed and immediately walked to me with Lettice.

“Mr. James Crofts, Your Majesty,” said Lettice.

He knelt with the utmost grace. I held out my hand and he put his lips to it, and lifted his very attractive dark eyes to my face.

“Please rise,” I said. “You may sit beside me. I have seen you here on one or two occasions.”

“Yes, Your Majesty.”

“Are you with your family?”

“I am with Lord Crofts, Madam.”

“He is your father?”

“No, Your Majesty, but I live with him.”

“I see.” I thought I must be misunderstanding, for though I was improving rapidly, there were occasions when I was baffled.

“And you have recently come to England?”

“Yes, Madam, I came with the household of Queen Henrietta Maria.”

“And Lord Crofts…your guardian…he is here today?”

“Oh yes, Madam.”

“You seem to know a number of people.”

“Oh yes, Madam.”

“And particularly Lady Castlemaine.”

“The lady is a friend of mine, Your Majesty.”

“Tell me how old you are.”

“I am thirteen years old, Your Majesty.”

“You have a tutor?”

“Oh yes, Madam, Thomas Ross. He is the King’s librarian. Before that it was Stephen Goff. He died, and when I came to England, it was Thomas Ross.”

“So great attention has been given to your education.”

“Yes, Madam. I want to grow up, though. I want to be done with education.”

Thirteen, I thought! At times he seemed much older, and then suddenly he was just a boy. I felt myself to be far more unworldly than he was.

“Is Lord Crofts a friend of the King?” I asked.

“Oh yes, Madam.” He went on to tell me that Lord Crofts had been with the King at the Battle of Worcester. “Do you know, Madam,” he cried with enthusiasm, “our forces were only thirteen thousand and Cromwell had thirty to forty thousand? It was small wonder we had to retreat.”

He spoke as though he had been there.

“You would have been a loyal supporter of the King,” I said.

“Of a surety, Madam. I could not have been aught else. Alas, I was not born then. I wish I had been with the King…riding through the country…disguised…to Whiteladies…to Boscabel. I never tire of hearing of it.”

“I, too, like to hear of it. The King has told me the stories…”

I was transported to those honeymoon days when, like the simpleton I was, I had thought Charles cared for me as I did for him.

“The King has been good to me,” said the boy almost shyly.

“It delights me to hear it.”

I looked up and saw that the King himself was coming toward us.

“Well met!” he cried. He smiled from me to James Crofts. “So, sir, you have been entertaining the Queen.”

The boy flushed slightly and lowered his eyes.

“I trust you found him amusing,” said Charles to me.

“I found him interesting company,” I replied.

“Then that pleases me. Well done, James Crofts. I am leaving now,” he went on. “Come.” He took my arm. “Perhaps you would care to share our coach, James Crofts.”

The boy’s eyes sparkled.

“Then let us go,” said Charles. “I trust, sir, that Thomas Ross will give a good account of your diligence?”

I marvelled that he knew so much about the boy, and I was very pleased that he had suggested I ride with him.

My joy was short-lived, for as I was about to step into the gilded coach which was to take us to Whitehall, I saw Lady Castlemaine sitting in it.

I was taken aback, although I knew that now and then she rode in the royal coach. I hoped the King would ask her to leave, as I was to ride with him, but he did no such thing, and I could not make a scene by refusing to ride with her. I had had my fill of scenes.

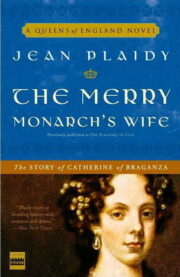

"The Merry Monarch’s Wife" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Merry Monarch’s Wife". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Merry Monarch’s Wife" друзьям в соцсетях.