“Then I am sure we can smooth it out.”

He then began to talk at some length of the King’s dilemma, and I gathered from his tone that I had been a little hasty and not as understanding as I might have been.

I was hurt and angry because it seemed that he believed I was the one who was in the wrong and that it was really rather foolish of me to make such trouble about an insignificant matter.

I looked at him steadily and said: “I do not think, my lord, that you and I see this matter in the same light. I will not have Lady Castlemaine in my household.”

My face was flushed and my heart was beating very fast. He was aware of my agitation and he rose quickly, saying he did not wish to distress me and would call again at a time more convenient to me.

I did not seek to detain him, and he left.

I tried to calm myself. I must not become so agitated at the sound of that woman’s name. All I had to do was refuse to see her. After all, was I not the Queen?

The next day Lord Clarendon called again. I felt much calmer and ready to talk to him.

“Pray be seated, my lord,” I said. “I am sorry for my reception of you yesterday. I was unprepared. I fancied that you believed the blame to be mine and I found that insupportable. I cannot see it in that light. I had looked upon you as my friend. I know you came on the King’s behalf and you have always been his most loyal servant. He has spoken to me of your fidelity to him at all times, but you must understand that I have suffered great anguish over this matter, which has made me a very unhappy woman.”

He replied earnestly that his great desire was to be of service to me. He would be very unhappy if, in explaining the effect my conduct had had on the King and how it would be wise to put matters right between us, he had appeared to be ungracious to me.

I replied that I was not averse to hearing if I had committed some fault.

He said: “Oh, Your Majesty, everything that has happened is very understandable. Your Majesty has had a restricted upbringing, if you will forgive my saying so. There are certain imperfections in mankind that have to be accepted, lamentable though they may be. I would point out, Madam, that these little failings are not only to be met with in this country.” He smiled wryly. “It has come to my knowledge that they exist in your own land in no small measure. But you have been sheltered. Your ears have never been sullied with these…er…little follies which are common to all mankind.”

“It is all so unexpected…”

“Your Majesty, you will agree with me that, had we sent an English princess to Portugal, she would not have found a court completely virtuous.”

“I cannot say…”

“Then I can assure Your Majesty that it would be so. The King has been devoted to you. Anything that happened before your marriage ought not to concern you, nor should you attempt to discover it.”

“I have not inquired into the past. I merely refuse to accept this woman into my household and she is being forced upon me. I do not want her. She is not a virtuous woman and therefore my ladies should not be expected to associate with her.”

“Madam, if the King insists…”

“If he insists, he exposes me to the contempt of the courts of Europe and shows he has no love for me.”

“I must warn Your Majesty that you should not provoke the King too far.”

“But it is he who is provoking me.”

“Accept this…as others have before you. The great Catherine de’ Medici accepted her husband’s affection for the Lady Diane de Poitiers, and she held her position at court. In fact, it was strengthened. It is all part of the duties of a Queen.”

“I wish to please the King, but I cannot accept that woman in my household.”

He gave up in despair, but he was not as despairing as I was.

I was deep in misery.

THAT NIGHT CHARLES CAME. I had never before seen him look as he did then. The tenderness was missing and he looked displeased.

“I hear you remain stubborn,” he said. “And I see that you have no true love for me.”

“Charles! It is because I love you! That is why I cannot bear to have this woman here.”

“I tell you, I have given her my word that she shall come.”

“That means that she will come…no matter what I want.”

“All I ask is that you receive her.”

I murmured: “To bring her here as you did…without warning. I cannot forget that you did that to me.”

“You should have controlled your venom against her. Instead of…”

“I know, I know. It was a distressing scene, but I had no control over it. Charles, it was due to my overwhelming grief, grief that I had been so deceived.”

“It is a great deal of fuss about a matter of no great importance.”

“If it is of no great importance, why do you insist that she comes?”

“I mean of no great importance to you. I can only marvel that you can behave so.”

I shouted at him: “Not so much as I marvel at your behavior.”

“You are completely unworldly. You reason like a child.”

“I reason like a wife who is ready to love and please her husband and has now been so ill-treated that her heart is broken. I wish I had never come here. I will go home. I will go back to Portugal.”

“It would be well for you to discover first whether your mother would receive you. I shall begin by sending back your servants. I have a notion that they maintain you in this stubborn attitude.”

We had both raised our voices and I thought afterward of how many people would be listening to us and how soon the news that the King and Queen were quarrelling over Lady Castlemaine would be spread round the court. It would reach her ears, and I was sure she would be gratified.

“You have not kept to your vows,” I cried.

“Can you upbraid me for that? What of your family? Did they honour our terms? Did they carry out the obligations of the treaty? What of the portion which was promised and was not there when the time came? What of the spice and sugar that has yet to be transformed into cash? If I were you, I should not talk too much of honouring vows.”

This was unkind. It was no fault of mine that the money which had been waiting had had to be used in our conflict against the Spaniards.

“Oh, I should never have come,” I said. “I want to go home.”

I saw the expression cross his face. He was shocked that, in spite of all this, I should want to leave him. And did I? I was not sure. I was too bitterly wounded to know what I wanted.

He seemed suddenly to decide he would hear no more. He left me in my misery.

CLARENDON CAME NEXT DAY. I think he was sorry for me, but at the same time he was determined to see this through the King’s eyes. I suppose that was his duty.

“Your Majesty, this has become a grievous matter indeed,” he said.

“The King was here last night. He was most ill-tempered.”

“I understand Your Majesty’s temper matched his. I have come this day hoping to persuade you to take the course which will be most advantageous to your happiness.”

“That must surely be to insist on not having that woman near me.”

“Will Your Majesty have the patience to listen to me if I try to explain how it appears to me…and to others? No wife should refuse to accept a servant who is esteemed and recommended by her husband.”

“How could such a woman be esteemed and respected by him?”

“If Your Majesty will forgive me, she is esteemed and recommended by the King, and if you refuse to receive her, what I ask you to remember is this: this thing will be done with or without your consent.”

I was silent.

He went on: “The whole court has been aware of the King’s devotion to you in the first weeks since your marriage. He sought no company but that of Your Majesty. Do you not see that you are charming enough to lure him from others? Have you such a low opinion of your attractions that you do not realize you can do this?”

I stared at him. I should have understood, of course. He was trying to help me. He was telling me that whether or not I agreed to Lady Castlemaine’s coming, she would do so because it was the King’s wish that she should. He would insist, since he had promised the lady. I did not know then, of course, of the power she had over him. I could not have understood then the depth of her sensuality, which matched his own. Temporarily I had had the appeal of innocence — unworldliness in a worldly court. I had had an initial advantage because I was so different from other women he had known. I did not know then that he would never have been faithful to me, but if I had been compliant, sweetly forgiving, I could have kept some hold on his affections. He was a man who hated trouble, and I was now causing him a great deal of it.

But I did not understand then. I could think only of what was right, and I firmly believed that to give my consent to that woman’s coming into my household must surely be wrong — and I determined to stand against it.

Clarendon was looking at me appealingly. But I did not understand.

I said: “The King will doubtless do as he wishes, but I shall never give my consent to that woman’s coming into my household.”

Clarendon shrugged his shoulders. He had done his best.

THOSE WERE VERY UNHAPPY DAYS. Charles and I scarcely spoke, and then only when absolutely necessary. He was not by nature a vindictive man. When he had returned to England and the Royalists had dug up the bodies of Roundheads and exposed them in public places, he had been the one to call a halt to the practice.

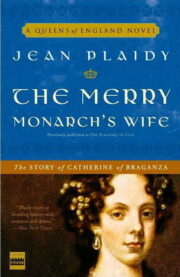

"The Merry Monarch’s Wife" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Merry Monarch’s Wife". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Merry Monarch’s Wife" друзьям в соцсетях.