I realized something when I lost my arm, he had said. And that was, my arm wasn’t the only thing I was missing. I was missing my heart. It lies with your mother. Always has.

Returning to the island had been his only option. It felt like it was written somewhere; it felt like he had been moved to do so by the hand of God.

Do you believe in God? Agnes had asked him.

I believe in something bigger, higher, and more important than ourselves that it is beyond human beings to comprehend, Clendenin said. Yes, I do.

Agnes grabbed Riley’s arm. “I can’t believe this happened. I met my father today. Half my blood, half my genes, half my biology.”

“It’s big,” Riley said. “It’s huge. Are you going to tell her?”

“Maybe,” Agnes said. “But not yet.”

“Are you going to see him again?”

“Thursday,” Agnes said. “Thursday after work. He wants to know about me, he said.”

“How does this make you feel about your other father?” Riley asked. “The professor?”

“Box,” Agnes said. “He’s my real father. Clendenin is…well, I don’t know what he is to me other than my DNA. But I want to find out. The question is, in finding out am I betraying Box?” She drank some more of her beer. “I don’t know. I’m so confused.”

“My two cents?” Riley said.

“Please.”

“Your mother is an extraordinary woman who has two men in her life. Probably, she loves them both.”

“Probably she does,” Agnes said.

“I bet it happens more than we think,” Riley said. “Although I am strictly a one-woman-at-a-time guy. But my parents always told me to be open to what they called the ‘wide spectrum of human experience.’ They were in the Peace Corps in Malawi before I was born, so they embrace tolerance, kindness, acceptance.” Riley put his hand on top of Agnes’s hand, which was still holding his arm, “I think it’s okay if you love them both, too, Agnes.”

Agnes looked at his arm, her hand, his hand, and then she started to cry. “I don’t know what’s wrong with me,” she said. “You’re being so understanding and you canceled Celerie for me and it is so easy to confide in you, and this situation is so screwed up and yet you’re making me feel like it’s not screwed up, you’re making me feel like I’m on a reasonable part of the spectrum of human experience and everything might end up okay.”

“And that’s why you’re crying?” he said. He pulled a box of tissues out of his center console and plucked one for Agnes.

What she didn’t say was that she knew that CJ, the man she was engaged to marry, wouldn’t have been this understanding. Because it was Dabney, he would have judged. He would have judged not only Dabney but Agnes as well. Her mother was a liar and a cheater and a slut-and therefore, so was Agnes. Agnes pictured CJ pulling Annabelle Pippin’s hair, twisting her arm. If CJ could see her now, sitting in Riley’s Jeep, he might hurt her. He just might. Agnes knew that the bad green gunk Dabney saw floating in the air around her and CJ wasn’t made up. CJ ridiculed Dabney’s matchmaking, but her mother was never wrong. And, Agnes feared, Manny Partida wasn’t wrong either. I couldn’t live with myself if I didn’t tell you.

Agnes also didn’t say that she was jealous of Riley’s future dental patients, all of whom would think he was the greatest dentist in the world. Riley would glide through his office like he was on roller skates. He would look at a recalcitrant seven-year-old patient and say, “Kissing girls yet, Sam?” And when that didn’t get Sam to open his mouth, he would say, “Hey, guess what I got for Christmas? Snowman poop!” And Sam would laugh and Riley would deftly move in with his instruments to count Sam’s teeth.

Agnes was also jealous of the young women in the audiences who would hear Riley play the guitar and sing Jack Johnson so beautifully that Jack Johnson himself would want Riley to serve as his best man or be godfather to his children. And Agnes was most jealous of the woman who would someday be Riley’s wife, the woman who would get to wake up next to him every morning and be the consistent recipient of his generous spirit.

Agnes didn’t say any of this, however. She carefully removed her hand from his arm, dabbed the tissue at her eyes, and took a deep, cleansing breath. The sky was streaked with the hot pink of the setting sun and Agnes wondered if this was the color Dabney saw when two people were a perfect match.

When Agnes got home, she listened to the fourth voice mail CJ had left on her phone. Where the fuck are you? And then, fearfully, she listened to the two later voice mails, which had no words, just the sound of CJ’s breathing. These, somehow, were even scarier. Agnes picked up the velvet box from her dresser and gazed at her engagement ring.

Tomorrow, she would send it back.

Dabney

The day Miranda left, Box announced that he realized that for the past three or four (read: eight or nine) years, he had bungled his spousal duties. He had not paid Dabney the kind of attention she deserved, he had not loved or appreciated her ardently enough. But now, all that was going to change.

He didn’t leave Dabney alone for a minute.

When she awoke, he was downstairs in the kitchen fixing her coffee. He let the Wall Street Journal lay on the table, untouched, and instead engaged Dabney in conversation. How had she slept? What had she dreamed about?

“What did I dream about?” Dabney said. “Who can remember?”

She said this to cover for the fact that she had dreamed about Clen; she dreamed about Clen all the time now. Last night, she and Clen had been naked, holding hands, circling. They were models for Matisse’s La Danse.

Next, Box asked what was going on at the Chamber. How were the information assistants working out, had a love affair started between the two of them? How was Nina Mobley, her kids must be nearly grown by now. Were any of them applying to college? And what of George Mobley? Did he still have a gambling problem?

Dabney stared at Box, nonplussed. It was possible that three or four or eight or nine years ago she had yearned for Box to take an interest in the daily minutiae of her life this way. For years, decades even, she had rattled on about this and that with only half, or a quarter, of his attention. It was as though he had stored up every detail she had ever told him in some mental vault that he had only now magnanimously decided to unlock. She wished he would pick up the Journal and let her drink her coffee in peace. Was it horrible of her to think this way?

Box wondered about the date and location of the next Business After Hours. He wanted to go with Dabney; there were people he hadn’t seen in years whom he wanted to catch up with. And what about trying a new restaurant this week? What about Lola Burger, or The Proprietors? Should he include Agnes, or would it be more romantic just the two of them?

Romantic? Dabney thought.

She said, “I’m going for my walk now.”

“Dabney,” Box said.

She stopped at the door and turned around.

“You have to make a doctor’s appointment,” he said.

“Yes,” she said. “I realize this.”

“If you don’t have time to call,” Box said, “then I’ll call for you.”

“I’ll call,” Dabney said.

“How’s your pain?” he asked.

“You have no idea,” she said.

Thank heavens for work. At work she was free, Nina knew all, so Dabney didn’t have to lie or pretend. She spent all morning planning the next Business After Hours, which would be held at Grey Lady Real Estate and catered by Met on Main. Dabney chuckled as she thought about how quickly Box would renege once he found out the locale. He detested all Realtors. In the spirit of Holden Caulfield, he believed them all to be phonies, and horrible gossips on top of it. And he had never wanted to go to Met on Main because there was a branch on Newbury Street in Boston that was supposed to be far superior. No, when push came to shove, he would pass on Business After Hours.

In the back office, both Celerie and Riley were on the phone; the rush leading up to August was upon them.

At noon, Dabney said, “I’m going to run some errands.”

Nina nodded her assent, and Dabney signed out on the log.

On top of the filing cabinet behind Nina’s desk were the wilting remains of the lilies Nina had received the week before from Dr. Marcus Cobb. Nina and Marcus Cobb were falling in love, and they were doing so without any help from Dabney. If Dabney interfered at this point, she would only mess things up. Her matchmaking ability seemed to be stuck in reverse.

Dabney turned to go, but at that moment they both heard the door downstairs open and then slam shut, and they heard footsteps on the stairs. Dabney worried that it was Vaughan Oglethorpe, and that at any second the office would be suffused with the smell of embalming fluid. Dabney would have to deal with Vaughan, and then light her green-apple-scented candles. She wanted to get to Clen; it had been four days since she’d seen him, and, like Nina’s flowers, she was starting to wilt.

“Hello, ladies!” The person walking into the office was…Box.

Nina gasped and Dabney felt so startled at the sight of him that she grabbed the edge of Nina’s desk.

“Darling!” Dabney said. “What are you doing here?”

“I was at home working when I had a revelation,” Box said. “I remembered how much you love that poem by William Carlos Williams, and so I brought you a cold plum.”

Dabney gaped at him. That poem by William Carlos Williams? “This Is Just to Say”-yes, Dabney had always loved that poem. In the years of Agnes’s growing up, a copy of the poem had been taped to the refrigerator door. It was an apology poem-forgive me, they were delicious, so sweet and so cold. Box was holding out the plum and a bottle of chilled Perrier with a silly grin on his face.

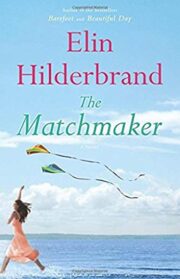

"The Matchmaker" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Matchmaker". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Matchmaker" друзьям в соцсетях.