She said, “I didn’t mean them when I said them. I have always loved you, Beast, and I always will.”

It was, all of it, something like a state of bliss, but it was coming to an end. They had been granted a week’s reprieve when Box called to say he was going to Washington.

“The president?” Clen had scoffed. “Are you sure he isn’t exaggerating his own importance?”

Box had flaws like everyone else, but exaggerating his own importance wasn’t one of them. Dabney was just grateful for an extra week of freedom.

Agnes, however, was growing more curious by the day. Where were you going today? I saw you driving on the Polpis Road. Why were you not at work? I called the office at three o’clock and they said you’d stepped out. Again. What’s going on, Mom? Is there something you want to tell me? Are you seeing Dr. Donegal again, because if you are, I think that’s great. Nina says you’re out doing errands. What kind of errands? Does Nina know where you’re going?

Dabney yearned to tell her daughter the truth.

Clen said, “Why don’t you?”

Maybe if she’d been having an affair with Dr. Marcus Cobb, or a young waiter from the Boarding House, she would have confided in her daughter. But Clendenin Hughes was a nuclear bomb.

A week after Agnes turned sixteen, Dabney had started teaching Agnes to drive in the parking lot of Surfside Beach. They went in the evenings after dinner, just the two of them, and Dabney rode shotgun and offered tips she thought might be helpful. They drove Dabney’s Mustang, which had been an impulse buy after her Camaro died. She’d had the Mustang for only eighteen months total (buying a Ford had been a mistake), but the car would have great importance to her because in it she had told Agnes the truth.

Dabney didn’t remember her exact words. What would she have said?

Honey, sweetheart, darling…Daddy-Box-isn’t your biological father. Your biological father is a man named Clendenin Hughes.

It had gone something like that.

He lives in Asia now. He left the country before I discovered I was pregnant and it was impossible for him to get back. It would have been far easier for me to go over there, but I couldn’t go, and so I told him to please let me raise you on my own. I’m not explaining this well, darling, it was very complicated.

Clendenin Hughes. He lives in Thailand now, I think, or Vietnam.

All Dabney could remember was Agnes’s high-pitched, hysterical screaming like Dabney was stabbing her in the eye with a fork.

She had waited too long. Dr. Donegal had said thirteen. Box had wanted her to know at age ten.

But Dabney was Agnes’s mother; Dabney was in charge of what her daughter knew, and when.

Dabney hadn’t wanted Agnes to know at all, ever.

What did it matter? Really, what? Box had been a good father. He had been with Agnes since before lasting memory. Why mess up Agnes’s beautiful head with information she would never, ever need?

Because it was the truth. Because it was blood. Dabney and Box had done a lot of, if not actual lying, then sidestepping of the truth. Agnes had asked why she looked nothing like Box and Box had said, “Human genetics are capricious, my pet.” Agnes had asked Dabney about the photographs of her and Clen together in the yearbook. This was your boyfriend, Mom? Yes, I suppose it was. Whatever happened to him? Oh, he’s long gone.

Agnes had never seen her birth certificate. Clen’s name wasn’t on it. Dabney wouldn’t allow it; she’d been too freshly wounded, too consumed with baffling emotion. Dr. Benton, who was the doctor on Nantucket before Ted Field, had done the delivery and he had every idea who the father was, but Dabney looked him dead in the eye and said she had no idea. She said she had slept with a lot of boys the preceding summer.

On the line for father, it said: unknown.

Dabney had decided to confess on Agnes’s sixteenth birthday because of the birth certificate. Agnes needed a copy to apply to a summer study program abroad, and whereas Dabney had been able to handle the birth certificate up until that point-for school registration, Little League, etc.-now it was impossible to keep it out of Agnes’s hands. Agnes could have taken five dollars to the registrar at any moment and gotten a copy herself.

The screaming. You lied to me. You lied about my very being. How can I trust anything you say ever again? How do I know you’re even my mother? I wish you weren’t. I wish you weren’t my mother.

Dabney was prepared for all this. Dr. Donegal had told her to expect it. Of course, it was one thing to know it was coming and another to actually experience it. Dabney was glad she had chosen to break the news while she was still in the driver’s seat of the Mustang. Agnes might have floored it-straight over the sand and into the ocean.

I wish you weren’t my mother.

Other girls Agnes’s age threw out lines like that all the time, Dabney knew, but Agnes never had. Dabney wouldn’t lie: it hurt, and it hurt worse because Agnes had every right to be angry. Dabney had withheld pertinent information, perhaps the most pertinent. Dabney had lied to her about her very being. Dabney had misjudged the timing. She had wholeheartedly disagreed with Box about telling Agnes at ten. What ten-year-old was mature enough to understand paternity? Agnes had only just learned what sex was. And at thirteen, Agnes had been going through puberty-she got her period, she started shaving her legs, her face broke out-no, Dabney wasn’t going to add to her worries by telling her about Clen.

At sixteen, Agnes was mature, responsible, intelligent, and calm. Dabney had thought she would take the news in stride. It explained why there were no pictures of Box with Agnes as a baby, and why they shared no physical characteristics.

But Agnes was hysterical. She was beyond angry, beyond upset. Dabney had driven from the Surfside Beach parking lot to their house on Charter Street while Agnes wailed. The windows of the Mustang were rolled up, but Dabney was still convinced that everyone on the island could hear.

When they reached the house, Agnes called Box in Cambridge. Dabney had thought that Agnes would be equally upset at Box for keeping the secret-but no. Agnes merely wanted Box’s confirmation that what Dabney had said was true (as if Dabney would lie about something like that?), and finding it so, she cried and cried, allowing Box, and only Box, to console her.

To Agnes, Dabney was the liar, the slut, the enemy. Agnes didn’t speak to Dabney for three weeks, and even after that, things were strained.

A mother first, a mother forever. Dabney had lived by these words, but that didn’t mean she hadn’t made mistakes. She had made a mistake in not telling Agnes sooner. I’m sorry, darling!

Box wasn’t happy with Dabney, either. She had suffered through a great big dose of I told you so.

Dabney wondered if she should have waited until Agnes was eighteen, or twenty-one. Maybe her mistake wasn’t in waiting too long but in not waiting long enough. Maybe she should have waited until Agnes had enough experience to realize that life was a complicated mess and you could count on being hurt the worst by the person you loved the most.

However, in the weeks following the revelation, she noticed that Agnes expressed curiosity about Clendenin Hughes. Dabney’s yearbooks ended up on the floor of Agnes’s bedroom. Agnes googled Clen on the family computer; she brought up a list of his articles and may even have read a few. And then Dabney found a letter addressed to Clen, care of the New York Times. It was lying on top of Agnes’s math textbook, in plain sight, as if Agnes had wanted Dabney to see it. More likely, it had been left there as a form of torture.

Dabney had wanted few things in life as much as she had wanted to read that letter.

Then, as it always did, summer arrived and Agnes attended her program in France, and she came home weeks later with a penchant for silk scarves at the neck, and for calling Dabney “Maman,” and a ferocious new love of macarons. She brought Dabney the foolproof baguette recipe, and mother and daughter baked bread together and ate it with sweet butter and sea salt-and once, magically, the addition of an ounce of dark chocolate-and everything pretty much went back to normal. Dabney was Mom, Box was Dad, and Clen’s name wasn’t mentioned again. Life went on.

But Dabney wasn’t naive. She knew she had done some real damage and inflicted some real hurt, just as her own mother had when she disappeared for good, leaving Dabney in the care of May, the Irish chambermaid. Dabney feared that perhaps her mothering was flawed and doomed because she had received such poor mothering herself.

But no-no excuses. Dabney had never felt sorry for herself; she was her own person. She had made a decision, right or wrong. We all make choices.

But to tell Agnes that Dabney was now in love with Clendenin Hughes, her biological father, and having an affair with him?

We all make choices?

No.

Dabney woke up in the morning unable to get out of bed. She couldn’t describe it. There was pain…everywhere.

Agnes said, “Do you want me to call Dr. Field?”

“No,” Dabney said. It was not stress, or guilt. She was lovesick. “Just call Nina, please, and draw the shades.” The sun was giving Dabney a headache; she wanted the bedroom dark. It was such a sin, Dabney wanted to cry, but there was no option. Her body felt invaded by pain, colonized by pain.

Agnes brought a glass of ice water and two pieces of buttered toast. The toast would never be eaten.

“I called Nina and told her you were sick,” Agnes said. “Can I bring you anything else?”

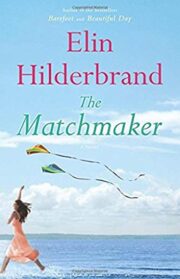

"The Matchmaker" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Matchmaker". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Matchmaker" друзьям в соцсетях.