“Lunchtime?”

“Noon or so,” he said. “You can check the log.” Next to them, the blond ponytail yammered on about her other favorite restaurant, Cru. Cru better for seafood, she said. American Seasons better for land animals.

Land animals? Agnes thought.

Riley Alsopp winked at Agnes. He said, “I’m still learning the ropes.”

Agnes said, “Is this your first summer?”

“First summer working here,” he said. “I’ve been coming to Nantucket since I was ten. I’m in dental school now, at Penn.”

That explained the teeth, Agnes thought. But not the Salinger or the board shorts. Agnes was confused about her mother. Dabney had left at noon or so, and she hadn’t come back? It was nearly three.

“Where did my mother go?” Agnes asked. “Did she say?”

Riley shrugged. “I’m not exactly privy to office secrets.”

“Right,” Agnes said. Did Dabney have a doctor’s appointment, maybe, that she hadn’t mentioned?

Riley said, “Are you coming to Business After Hours tonight? It’s at the Brotherhood of Thieves.”

“No,” Agnes said. “I don’t go to those anymore. I got dragged to them as a kid. By the time I was fifteen, I had sneaked more than my share of bad Chardonnay.”

Riley laughed. The guy was so cute, her mother must have pounced on him immediately, and maybe forgiven him the board shorts.

“Well, Riley, it was nice to meet you,” Agnes said. Her inflection, she realized, was eerily like her mother’s at that moment. She turned, and was dismayed to find Nina still on the phone. Nina would know where her mother was.

The blond ponytail hung up her phone and announced to the room, “Those folks are definitely coming to Nantucket for a week in September!” She put two fists in the air in a V for victory. Then the blond ponytail noticed Agnes and nearly vaulted over her desk.

“You must be Agnes!” she said. She offered Agnes an extremely strong handshake. “I’m Celerie Truman. This is my second year as an information assistant here at the Chamber. I am a really, really big fan of your mother’s.”

Agnes suppressed the urge to laugh. Where did Dabney find people with such wholesome energy?

“Oh, hi!” Agnes said, again channeling her mother’s tone. “Nice to meet you, Celerie.” She paused, hoping she had pronounced the girl’s name correctly. Celerie like celery? What had her mother thought of that? Dabney was very particular about names. She believed that the only suitable names were those befitting a Supreme Court justice: Thurgood Marshall, Sandra Day O’Connor. Celerie was not a Supreme Court justice name.

“I hope you’re coming to Business After Hours,” Celerie said. “It’s at the Brotherhood, which is my other other favorite restaurant. My casual favorite.”

“Sadly, I won’t be there tonight,” Agnes said. She sounded so much like her mother it was frightening, but the words were coming out that way unbidden. She heard Nina getting off the phone. “Excuse me!” She waved at Celerie Truman and Riley Alsopp. They were so gorgeous, both separately and together, that Agnes wondered if the back room of the Chamber was a matchmaking laboratory this summer. Leave it to her mother.

Agnes presented herself at Nina’s desk. “Where’s Mom?”

Nina clasped her hands at her bosom. “Tell me about New York!” she said. “Is it wonderful? And you’re getting married! At Saint Mary’s and the Yacht Club, your mother said.”

There was catching-up required. Agnes knew this. She hadn’t had a chance to talk with Nina at Christmas or on Daffodil Weekend. Nina Mobley had five children to ask after; Agnes had babysat for all of them. But Agnes didn’t have the presence of mind for chitchat right now.

She quickly checked the log. Dabney had signed out at five minutes to noon, listing errands/lunch as the reason for her absence.

“So, wait, I’m sorry,” Agnes said. “Did Mom say where she was going?”

Nina took a deep breath, then emitted a nervous laugh. “She had errands.”

“Errands?” Agnes said. “What kind of errands?”

Nina Mobley squinted at Agnes. “Oh, honey,” she said. “I wish I could tell you.”

Agnes walked home, thinking that she and her mother must have just missed each other-or that Dabney had run to the grocery store for more eggs, or to Bartlett Farm for hothouse tomatoes. But would she do that in the middle of a workday? Never! And those errands wouldn’t take three hours. Dabney had been acting strange, Box said. Dabney did have a slew of peculiarities-a rare form of OCD and agoraphobia that made her incapable of leaving Nantucket-and then her mystical matchmaking power. Maybe she was seeing Dr. Donegal, her therapist. Or maybe she was having a midlife crisis and Agnes would find her in the cool dim of the Chicken Box, drinking beer and shooting pool.

Ha! Agnes was making herself laugh. Dabney would be at home.

But Dabney wasn’t at home. Agnes felt irrationally upset about this, as if she were a child who had been abandoned. And, to boot, her mother’s cell phone was lying on the kitchen counter, charging. Really, what good was a cell phone if you didn’t take it with you when you left the house? Agnes considered calling Box in London. It was nine thirty at night over there; Box would probably be at dinner. Agnes hated to interrupt him-and besides, what would she say? Mom left work three hours ago and I don’t know where she went. The island was only so big; Dabney had to be somewhere.

Agnes trudged up to her bedroom and threw herself across her bed. She was tired enough to sleep until morning.

She awoke to the strains of Alicia Keys singing “Empire State of Mind,” her cell phone’s ringtone, handpicked for her by one of the little girls at the Boys & Girls Club. Agnes was groggy and her limbs felt leaden, but she reached for her phone, thinking it would be her mother.

She saw when she picked up that it was five o’clock and that it was CJ calling. How had she slept for so long? What was wrong with her? She considered letting the call go to her voice mail; CJ would sense sleep in her voice and she didn’t feel like explaining that she had eaten five thousand calories already that day and had just woken up from a two-hour nap. But CJ did not like getting Agnes’s voice mail. When he called, he expected her to answer.

She cleared her throat. “Hello?”

“Agnes?” he said. “Are you okay?”

She stretched out like a cat. The room was catching the mellow slant of the late-afternoon sun across the wooden floor. Agnes’s apartment, as lovely as it was, didn’t get this kind of natural light. In the background of the phone call, Agnes heard sirens and hubbub, the city. She didn’t miss it one bit.

“Yes,” she said. “I’m fine.”

“You didn’t call once today,” CJ said. “I thought you couldn’t live without me.”

“Oh,” Agnes said. “Well, I can’t.”

“Good,” CJ said. “I just left the office. I’m headed to the gym and then I’m meeting Rocky for a game of squash. What are you up to?”

Agnes sat up and listened to the rest of the house for sounds of her mother. The house was silent. “Nothing.”

“You and your mom have big plans tonight?” CJ asked. “Peanut butter sandwiches and Parcheesi?”

“No plans,” she said.

“Is everyone on Nantucket aflutter with the news of your return? Are all your old boyfriends banging down your door?”

“No,” Agnes said archly.

“Hey, baby, don’t get angry. If anyone should be angry, it’s me. I have to live here in the big city without the woman I love.”

“We’ll be together in ten days,” Agnes said.

“If I make it up there,” CJ said. “I can’t stay in your parents’ house again. I hate to be a diva that way, but I’m just too old. I’m on the wait list for a room at the White Elephant, so we’ll keep our fingers crossed for that. Otherwise, you can come home to New York.”

Agnes blew her nose. She didn’t want to go back to New York. She had just arrived on Nantucket and she wanted to stay and enjoy it. Her job as a counselor at Island Adventures camp started the next day. Agnes wanted a routine. She wanted sun and beach and ocean air. She wanted to be with her mother.

“It would be much better if you could come here,” Agnes said.

“Well,” CJ said. “We’ll have to wait and see.”

Agnes thought again about what Manny Partida had told her. Agnes didn’t think CJ would ever hurt her. But she hated being spoken to like a child.

“I hear my mother downstairs,” Agnes said. “I should go. I’ll call you later, baby. Bye.”

But downstairs was quiet and growing darker. Dabney hadn’t returned. She had gone back to the office, Agnes supposed, after running her mysterious errands, and now she would be headed to the Brotherhood, for Business After Hours.

Dabney pulled the yellow dress out of the shopping bag and stared at it for a long minute.

If I make it up there.

She shucked off her shorts and T-shirt and slipped on the dress. Mascara, lip gloss, a hand through her hair, and a pair of gold sandals. She would stop in at Business After Hours, she decided, for old times’ sake.

Glass of mediocre Chardonnay in hand-it was a step up from the boxed wine of her teenage memory-Agnes threaded her way through the party in search of her mother. The best part of the Brotherhood was the old part-a basement grotto with low, beamed ceilings and stone walls and scarred wooden tables. Agnes had loved to come here growing up, although, for some reason, Dabney allowed it only when it was raining. The room was lit by candles; it had the contained coziness of the hull of a ship. Agnes always used to order the Boursin cheese board. Bread, butter, cheese, mustard, pickles, candlelight, rain, sometimes an acoustic-guitar player-it was a good memory that distracted Agnes for a minute.

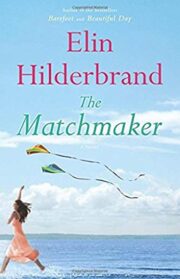

"The Matchmaker" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Matchmaker". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Matchmaker" друзьям в соцсетях.