Freeloader, he called her. Good for nothing. She doesn’t realize the value of money because she never had to earn it.

Aside from this, CJ didn’t say much about Annabelle or about why the marriage had failed, even though Agnes had repeatedly asked. CJ said that both he and Annabelle had signed a paper agreeing never to discuss the particulars of their split. A gag order. This had sounded reasonable at the time, but after what Agnes had heard from Manny Partida a few weeks earlier, Agnes wasn’t so sure. She thought spending the summer away from CJ might be the best thing.

Manny Partida was Agnes’s boss, the regional director, the head of every Boys & Girls Club in New York City. He was the one who had come in to tell Agnes that National wouldn’t be funding any summer programs for her club that year. Agnes was devastated; she had more than six hundred members, and what exactly were those kids supposed to do all summer without any programming? Agnes loved the kids at her club in direct proportion to how little they had. Her favorite children, ten-year-old twins named Quincy and Dahlia, were homeless; they lived with their mother in a shelter, but not always the same shelter. They each brought a rolling suitcase to the club, which Agnes kept safe in her office so that no one would pilfer their things. Dahlia liked to make fairy houses out of twigs and grass and sometimes even old straws and McDonald’s cups that she found on the perimeter of the club’s crumbling asphalt basketball court. Agnes could have cried just thinking about the two of them without a safe place to go all summer.

As if this weren’t upsetting enough, Manny had another bomb to drop.

He said, “A little bird told me you’re engaged to Charlie Pippin?”

“CJ,” Agnes said. “Yes, I am.” She looked down at her left hand, though her fingers were bare. The diamond CJ had given her was too valuable to wear safely to work.

“When I knew him, which wasn’t that long ago,” Manny said, “he went by Charlie.”

“You knew him?” Agnes said.

“He was a big donor, one of the biggest, at the Madison Square Club, ten, twelve years ago,” Manny said. “He and his first wife.”

Agnes nodded. On one hand, she didn’t want to hear about CJ and Annabelle, and on the other hand, she craved every detail.

Manny said, “I realize people change.”

Agnes smiled uncertainly. “Excuse me?”

“People change,” Manny said. “He changed his name, and he switched affiliations to the Morningside Heights Club, which is good because you can certainly use the money. But I’d advise you to be careful.”

“Careful?” Agnes said.

“Rumor has it he wasn’t very nice to his first wife.”

“Wasn’t nice?” Agnes said.

Manny held up his palms. He wore a light blue T-shirt under a khaki suit and a three-inch silver cross on a chain around his neck.

“I’m not saying he hit her, because I don’t know the specifics. But there were stories flying around for a while. Something happened at one of the benefits for the Madison Square Club. They had both been drinking, the wife had bid on something quite expensive without asking his permission, he lost his temper, and I heard…” Here, Manny trailed off. “This is just what I heard, Agnes, and so take it with a grain of salt. But I couldn’t live with myself if I didn’t tell you. I heard he got physical with her.”

“What?”

“Hair pulling, arm twisting, some not-so-nice stuff.” Manny stood up. “But again, that was ten, twelve years ago, and people change. Just please, Agnes, please be careful. You’re one of the best directors I have, and I only want to see you happy.”

Manny Partida had left the office, and Agnes had sat glued to her chair for a long while, thinking that Manny Partida was full of shit, or whomever was feeding his ear was; the people at the Madison Square Club were probably mad or jealous that CJ had moved his financial allegiance uptown, and that he had brought Victor Cruz in to sign autographs! Lorna Mapleton, who was the director at Madison Square, was in her sixties; she thought Agnes was too young to be at the helm of a club. Physical? Agnes couldn’t imagine CJ being physical with her. It was true he had a temper, especially when he was drinking, and Agnes had heard him slice people to ribbons over the phone. But he was always gentle with Agnes, he cared about her well-being, that was why he liked her to exercise every spare moment and why he watched her diet-no carbs, no cheese, no sauces. Her body was his temple, he said. He would never hurt her.

Agnes hadn’t told Dabney what Manny Partida said-God, no, that would have sent Dabney into a tailspin-but Agnes had decided on the spot that she would spend the summer at home on Nantucket.

That first afternoon, Agnes walked into town. She wasn’t a town person the way Dabney was. Dabney loved town. For her, the allure of Nantucket was found on the grid of four square blocks. This was where the action was-the real estate agents, the insurance agents, the pharmacy with lunch counter, the art galleries and florists and antiques stores, the churches, the post office, the administration buildings, the clothing boutiques, the T-shirt shops. Town was where the people were. Dabney loved people, and anyone found on the streets of Nantucket, if only for an hour or two on a day trip, she thought of as “her people.”

Agnes, on the other hand, preferred anonymity, which was why she liked Manhattan. This might have been a response to growing up as Dabney Kimball’s daughter. She had never gotten away with anything as a teenager; if she took a drag of a cigarette on the strip off Steamship Wharf or if she held hands with a boy on the bench outside the Hub, it was reported back to Dabney within the hour. This was why Agnes preferred the quieter, more remote parts of Nantucket-the far-flung beaches, the trails through the state forest, the secret ponds.

But today she felt otherwise. Today she wanted to be recognized as Dabney Kimball’s daughter. She stopped in at Mitchell’s Book Corner and browsed for a moment, then she crossed the street to check out the cute party dresses at Erica Wilson. She tried on a flirty yellow number and bought it on a whim-it was bright, the color of summertime. In the city, she, like everyone else, tended to wear black.

She window-shopped, meandering like a tourist, and was shocked when nobody recognized her. Ms. Cowen, who had been Agnes’s field-hockey coach, walked right past her. Of course, Agnes hadn’t lived here since graduating from high school. And she had cut her hair. But still, Agnes felt weirdly displaced. This was where she was from, but she didn’t quite belong here.

There was only way to rid herself of this feeling. She headed upstairs to the Chamber of Commerce office.

The Nantucket Chamber of Commerce was located above what used to be an old bowling alley, and the office always smelled vaguely of bowling shoes. To combat this, Dabney occasionally lit green-apple-scented candles. The combination of bowling shoes and green apple came to define the Chamber and, by association, Dabney herself.

When Agnes walked in, she was greeted by a shriek-happy, excited, perhaps a touch manic.

Nina Mobley.

“Agnes! Your mother told me you were here, but I didn’t think I’d be lucky enough to see you on the first day!”

“Hey, Nina,” Agnes said, bending down to give Nina a squeeze. Nina, like Dabney, seemed never to change-frizzy brown hair, gold cross at the neck, squinty eyes. Nina had always been a squinter, as if the world lay just out of focus.

Agnes noticed that Dabney’s desk was unoccupied, and by habit she poked her head into the “back room,” where the information assistants sat, answering the phones. There was a girl with a high, blond ponytail chattering away about her “favorite restaurant, American Seasons”-and at the near desk sat a guy with thick brown hair that curled up at the collar of his pale blue polo shirt. The two of them were so cute and perfect that Dabney might have picked them out of a catalog. The guy was finishing off a frappe that Agnes identified as having come from the pharmacy lunch counter across the street; he was at the slurpy-sounding end. When he looked up and saw Agnes, he jumped to his feet. She noticed that he was wearing Hawaiian-print board shorts and flip-flops, which were both in violation of Dabney’s usual dress code.

“Oh, hey!” he said. “I’m so sorry. Can I help you? I’m Riley Alsopp.”

Agnes smiled. He seemed quite earnest; he must be new, maybe too new to know about the no-beachwear rule. Agnes had worked as an information assistant one summer, and she had hated it. Her mother had made her wear a knee-length khaki skirt and button-down oxford shirts. (“I look like you,” Agnes had complained.) Her mother had insisted that when Agnes wasn’t on the phone with potential visitors, she should be memorizing the Chamber guide and learning the arcane details of the island’s whaling history.

Riley, however, had a copy of Salinger’s Raise High the Roof Beam, Carpenters and Seymour, An Introduction open on his desk. Odd. He was too old for a summer reading list.

“I’m Agnes,” she said. “I’m…”

“Dabney’s daughter,” he said. “Your mother talks about you all the time. And I’ve seen your picture.” He smiled at her, showing off very straight white teeth.

Agnes turned around. Unlike most offices, where the bosses hid in the back, here Dabney and Nina sat in the front room. This, of course, was Dabney’s idea. She wanted to be the first person someone encountered when he or she walked into the Chamber. But Dabney’s desk was still empty, and now Nina Mobley was on the phone.

“Where is my mother?” Agnes asked Riley Alsopp. “Do you know?”

“She went out around lunchtime,” Riley said. “And she hasn’t been back.”

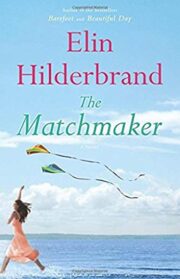

"The Matchmaker" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Matchmaker". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Matchmaker" друзьям в соцсетях.