I had badgered her to tell me the story. "Well," she said, "it's like this. You see the cot there. There's a little baby in it. Now that baby didn't ought to have been born because the sailor had been away for three years and she's had this little baby while he was away. He don't like that ... and she don't either."

"Why doesn't he? You'd think he'd be glad to come home and find a little baby."

"Well, it means that it's not his and he don't like that."

"Why?"

"Well, he's what you might call jealous. There was a pair of them pictures. My mammy split them up when she died. She said, 'The Return is for you, Matty, and The Departure is for Emma. Emma's my sister. She married and went up north."

"Taking The Departure with her?"

"She did. Didn't think much of it either. But I'd have liked to have the pair. Though The Departure was very sad. He killed her, you see, and the police was there to take him away to be hanged. That's what The Departure meant. Oh, I'd have loved to have The Departure."

"Matty," I asked, "what happened to the little baby in the cot?"

"Someone took care of it," she said.

"Poor baby! It had no mother or father after that."

Matty said quickly: "Tom was in here telling me about that there postbox you've got at school. I hope you've done a nice one for Tom. He's a good boy, our Tom is."

"I've done a lovely one," I said, "of a horse."

"Tom'll like that. He's a rare one for horses. We're thinking of putting him to learn with Blacksmith Jolly. Blacksmiths have a lot to do with horses."

Sessions with Matty always came to an end too soon. They were always overshadowed by the knowledge that Aunt Amelia would be expecting me home.

Crabtree Cottage was cheerless after Matty's. The linoleum on the floor was polished to danger point and there was no holly propped up over the pictures of Christ and St. Stephen. It would have certainly looked out of place there and to have stuck a piece over the disagreeable Queen would have been nothing short of lese majesty.

"Dirty stuff," had been Aunt Amelia's comment. "Drops all over the place and the berries get trodden in."

The day of the party came. We did our singing, and the more talented of us—I was not among them—recited and did their solos. The postbox was opened. Tom had sent me a beautiful drawing of a horse and on the paper was written: "A merry Christmas. Yours truly, Tom Grey." Everyone in the school had sent everyone else a card, so it was a big delivery. The one I had from Anthony Felton was meant to wound rather than carry good wishes. It was the drawing of a witch on a broomstick. She had streaming dark hair and a black mole on her chin. "Wishing you a spellbinding Christmas," he had written on it. It was very badly drawn and I was delighted to note that the witch on it was more like Miss Brent than like me. I had had my revenge by sending him the picture of an enormously fat boy (Anthony was notoriously greedy and more than inclined to plumpness) holding a Christmas pudding. "Don't get too fat to ride this Christmas," I had written on it; and he would know that the card carried with it the hope that he would.

A few snowflakes fell on Christmas Eve and everyone was hoping it would settle. Instead it melted as soon as it touched the ground and was soon turning to rain.

I went to the midnight service with Aunt Amelia and Uncle William, which should have been an adventure because we were out so late; but nothing could really be an adventure when I walked between my two stern guardians and sat stiffly with them in the pew.

I was half asleep during the service and glad to be back in bed. Then it was Christmas morning, exciting in spite of the fact that there was no Christmas stocking for me. I knew that other children had them and thought it would be the height of fun to see one's stocking bulging with good things and plunging one's hand in to pull out the delights. "It's childish," said Aunt Amelia, "and bad for the stockings. You're too old now for such things, Suewellyn."

Still I had Anabel's presents. Clothes again—two dresses, one very beautiful. I had only worn the blue one she had given me once, and that was when she came. Now there was another silk one and a woolen one and a lovely sealskin muff. There were three books as well. I was delighted with these gifts and my great regret was that Anabel was not there to give them to me in person.

From Aunt Amelia there was a pinafore and from Uncle William a pair of stockings. I could not really feel very excited about them.

We went to church in the morning; then we came home and had dinner. It was a chicken which brought reminders, but there was no mention of wishbones. Christmas pudding followed. In the afternoon I read my books. It was a very long day. I longed to run across to the Greys' cottage. Matty had gone next door for the day and there were sounds of merriment spilling out on the green. Aunt Amelia heard it and tut-tutted, saying that Christmas was a solemn festival. It was Christ's birthday. People were meant to be solemn and not act like heathens.

"I think it ought to be happy," I pointed out, "because Christ was born."

Aunt Amelia said: "I hope you're not getting strange ideas, Suewellyn."

I heard her comment to Uncle William that there were all sorts at that school and it was a pity people like the Greys were allowed to send their children and mix with better folk.

I almost cried out that the Greys were the best folks I knew, but I was aware that it was no use trying to explain that to Aunt Amelia.

There was Boxing Day to follow ... another holiday and even quieter than Christmas Day. It was raining and the southwest wind gusted over the green.

A long day. I could only revel in my presents and wonder when I should wear the silk dress.

In the New Year Anabel came. Aunt Amelia had lighted a fire in the parlor—a rare event—and she had drawn up the Venetian blinds, for she could no longer complain of the sun's doing harm to her furniture.

The room still looked dismal in the light of the wintry sun. None of the pictures took any cheer from the light. St. Stephen looked more tortured, the Queen more disagreeable and Christ hadn't changed at all.

Miss Anabel arrived at the usual time, which was just after dinner. She looked lovely in a coat trimmed with fur and a sealskin muff, like the big sister of mine.

I hugged her and thanked her for the gifts.

"One day," she said, "you're going to have a pony. I am going to insist."

We talked as we always did. I showed her my books and we discussed school. I never told her about the teasing I received from Anthony Felton and his cronies because I knew that would worry her.

So the day passed with Anabel and in due course the fly came to take her back to the station. It seemed like just another of Anabel's visits, but this was not quite the case.

It was Matty who told me about the man at the King William Inn.

Tom was working there after school, carrying luggage into rooms and making himself generally useful. "It's a second string to his bow," said Matty. "In case it don't work out with the blacksmith."

Tom had told her about the man at the inn and Matty told me.

"A regular shindy-do there was up at the King William," she said. "He was a very high and mighty gentleman. Staying there in the best room. He arrived in a temper, he did. It was all along of there being no fly to take him to the King William when he got off the train. Well, how could there be? The fly was in use, wasn't it?" Matty nudged me. "You had a visitor yesterday, didn't you? Well, Mr. High and Mighty had to wait, and there's one thing that kind of gentleman don't like much ... and that's being kept waiting."

"It doesn't really take long for the fly to come to Crabtree Cottage and go back to the station."

"Ah, but rich important gentlemen don't like waiting one little minute while others is served. I had it from Jim Fenner." (He was our stationmaster, porter and man of all work at the station.) "There he was standing on the platform ranting and raging while the fly went off carrying your young lady in it. He kept saying, 'Where is it going? How far?" And old Jim he says, all upset like, because he could see this was a real gentleman, Jim says, 'Well, sir, it won't be that long. 'Tas only gone to Crabtree Cottage on the green with the young lady.' 'Crabtree Cottage,' he roars, 'and where might that be?'' Tis only on the green, sir. There by the church. Not much more than a stone's throw. The young lady could walk it in ten minutes. But she always takes the fly like and books it to bring her back to catch her train.' Well, that seemed to satisfy him and he said he'd wait. He asked Jim a lot of questions. He turned out to be a talkative sort of gentleman when he wasn't angry. He got all civil like and gave Jim five shillings. It's not every day Jim sees the likes of that. He says he hopes that gentleman stays a long time."

I couldn't stay talking to Matty, of course, so I left her and ran back to the cottage. It was getting dark early now and we left school in twilight. Miss Brent had said we should leave at three o'clock in winter because that would give the children who lived farther away time to get home before darkness fell. In the summer we finished at four. We started at eight in the morning instead of nine as in the summer and it was quite dark at eight.

Aunt Amelia was putting some leaves together. She said: "I'm going to take these to the church, Suewellyn. They're for the altar. It's a pity there are no flowers at this time of the year. Vicar was saying it looked bare after the autumn flowers were finished, so I said I would find some leaves and we would use them. He seemed to think it was a good idea. You can come with me."

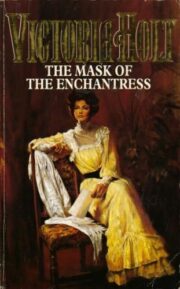

"The Mask of the Enchantress" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Mask of the Enchantress". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Mask of the Enchantress" друзьям в соцсетях.