"I don't reckon that, Mrs. Cringle."

"Then I reckon it's something what brings you here, Miss Susannah. We'd rather you told us outright."

"I want to get to know everyone on the estate."

"Why, Miss Susannah, you've known most of us all your life. Of course, there was that time when you went away when Mr. Esmond was took bad and come near to dying and our Saul ..."

"Hush your tongue, woman," said the old man. "Miss Susannah don't want to hear about that. I reckon that's the last thing she wants to hear about."

"I think we want to turn to the future," I said.

The old man gave a hoarse chuckle. "That's a good way, miss, when the past don't bear looking into."

The cider was indeed strong and they had given me a large tankard. I wondered whether I could in politeness leave it. No, I decided, they were too prickly as it was.

I drained the tankard and rose to my feet. The cider was evidently potent. The farmhouse kitchen was looking a little hazy. I was aware of them all watching me with a sort of sly triumph. Not the girl though; she was indifferent; she had too many problems of her own to care for victory over me. I could understand that if she were in fact illegally pregnant. I imagined what that would mean in a household like that.

I was untying the horse when the boy I had seen on my arrival ran up to me.

"Help me, miss," he said. "My cat's caught up in the barn. I can't reach her. You could. She's crying. Come and help me."

"Show me the way," I said.

His face broke into a smile. "I'll show you, miss. Will you get her down for me?"

"I will if I can."

He turned and started to walk quickly. I followed. We went over a field to a barn, the door of which was swinging open.

"The cat ... she got in ... high up ... and she can't get down. You can get her, miss."

"I'll try," I said.

"In here, miss."

He stood aside for me to enter. I did so and the door was immediately shut. I was in complete darkness and could see nothing after the light outside.

I cried out in astonishment, but the boy was gone and I heard a bolt slide. Then ... I was alone.

I looked about me and suddenly I felt the goose pimples rise on my flesh. I had heard people talk of their hair standing on end. I had never experienced it before, but I did then. For hanging from one of the beams was the body of a man. He was swaying on a rope, turning slightly as he did so.

I screamed. I cried: "Oh ... no ... !" I wanted to turn and run.

Those first seconds were terrible. The boy had shut me in here with a dead man ... moreover a man who had hanged himself or been hanged by others.

Terror gripped me. It was so dark and eerie in the barn. I could not bear this. The boy had done it deliberately. There was no cat ... only a body hanging on a rope.

I was trembling. I had been lured here for a purpose. That boy must have known what was here. Why had he done this to me?

Panic seized me. I did not know which way to turn.

The barn was some distance from the farmhouse. If I shouted, would they hear ... and if they did would the Cringles come and help me?

The last thing they would do was that. I could feel the waves of hatred coming towards me in that farmhouse kitchen ... from all except the girl Leah. She had too many problems of her own to consider me.

A terrible inadequacy came over me. What should I do? Suppose he wasn't dead. I must try to get him down. I must try to save him. But my first impulse was to escape, to call someone, to get help. I tried to push open the door but it had been bolted from the outside. I shook it. But the barn was a flimsy structure and it shook as I banged on the door.

I had to see whether the man was alive. I had to get him down.

I felt sick and inadequate. I longed to be out in the sunshine, away from this horrible place.

I looked again towards that grisly sight. I could see now that the figure was limp and lifeless. There was something about the way it sagged that told me that.

I stared at it in horror, for it had swung round and I was looking at a grotesque face ... a face that was not human. It was white ... white as freshly fallen snow, and it had a grinning gash of a mouth the color of blood.

It was not a man. It was not a human being, though the corduroy breeches and the tweed cloth cap were those of a man who worked on the land.

I moved forward but every instinct rebelled against my going near the thing.

I suddenly felt I could not stay there a moment longer. I banged on the door and called out: "Let me out. Help."

I kept my back on the thing that was hanging there. I had an uncanny feeling that it might come to life, detach the rope about its neck and come over to me and then ... I knew not what.

The cider was having an effect on me—making me a little lightheaded. It was no ordinary cider. I believed that they had deliberately given me too much of their strongest brew. They hated me, those Cringles. Who was the boy who had shut me in the barn? A Cringle, I was sure. It must be. I had heard there were two sons and a daughter.

I started to hammer on the door again. I went on shouting for help.

My eyes slewed round. It was there ... that horrible grinning thing.

I must try to be calm. I asked myself what this could mean. The Cringles had done this. They wanted to frighten me. They must have told the boy to bring me out here and lock me in. For what purpose? Did they intend to keep me here? To kill me perhaps?

That was too preposterous, but I was frightened enough to think anything possible.

I must get out of here. I could not bear to stay in this barn with that horrible grinning thing looking at me as it swayed on its rope.

I shouted again. I banged on the door until it shook under my blows. What a hope! Who would pass this way? Who would hear me? How long must I stay here shut in with that thing?

I leaned against the door. I must try to think rationally, calmly. I had been locked in here by a mischievous boy. But what was the significance of that hanging figure? Why should the boy bring me here with the story of a trapped cat? Boys were mischievous by nature. Some of them enjoyed playing unpleasant practical jokes. Perhaps the boy had thought it would be funny to lock me in here with that thing. It was the boy I had seen when I arrived at the farm. He must be a Cringle. He could have hung up the figure there and then waited for me. Why? There was some meaning behind it, I was sure.

I could not stay here forever. I should be missed. But who would know where to look for me?

If I went to that thing ... examined it more closely ... But I could not bring myself to do that. It was so uncanny, so horrible in the gloom. It was like a ventriloquist's dummy. But there was something about this one. ... It seemed alive.

I hammered on the door again. My hands were grazed. I shouted as loudly as I could for help.

Then I Listened tensely, and my heart leaped with hope, for I heard a voice.

"Hello... . What's wrong? Who's there?"

I banged with all my might on the door. The barn seemed to shake.

Then there came the sound of horse's hoofs and the voice again. "Wait a minute. I'm coming." The horse had stopped. There was a brief silence. Then the voice was closer. "Wait a minute." Then the bolt was being drawn. I heard it scrape out of the sheath. A shaft of light came into the barn and I almost fell into the arms of the man who was coming in.

"Good Lord!" he cried. "What are you doing here, Susannah?"

Who was it? I did not know. In that moment I had time for nothing but relief.

He held me against him for a moment and he said: "I thought the barn was coming down."

I stammered: "A boy lured me here and ... bolted the door. I looked up and saw ... that."

He stared at the thing swaying on the rope.

He said slowly: "My God! What a trick to play ... what a foolish joke."

"I took one look at it and thought it was a man. The face was round the other way then."

"Will they never forget? ..."

I did not know what he was talking about, but I was now realizing that I had been brought out of a terrifying situation into a very dangerous one.

He had gone over to the figure and was examining it.

"It's one of their scarecrows," he said. "Whatever made them string it up like this?"

"He told me his cat was trapped in here."

"One of the Cringle boys, was it?"

I took a chance. I gathered I ought to know the Cringle boys. I nodded.

"This is too much. Some people would have had a heart attack. You're made of stronger stuff, Susannah. Let's get out of here, shall we? Have you your horse nearby?"

"Yes, near the approach to the farm."

"Right We'll go back. I came this morning. Heard you'd gone out round the estate and thought I'd come and look for you."

We came out into the sunshine. I was still trembling from my experience but I had recovered sufficiently to take stock of him. He was tall and what struck me most about him was an air of authority. I had noticed it and admired it in my father and I realized in that moment that it had been lacking in Philip. The man's hair was dark and there was a penetrating look in his brown eyes which would have warned me if I had not been in such a state of shock. He seemed to notice my scrutiny, for he said: "Let me have a look at you, Susannah. Have you changed much since your circumnavigation of the world?"

I avoided his gaze and tried not to look as uneasy as I felt.

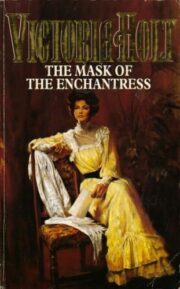

"The Mask of the Enchantress" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Mask of the Enchantress". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Mask of the Enchantress" друзьям в соцсетях.