She was mollified. She accepted my excuses. But what a fuss over a pudding. How careful I had to be!

I was exhausted when I reached my bedroom. I had learned a great deal and the most important thing I had discovered was how easily I could be betrayed.

I slept well. I suppose I was worn out physically and mentally. I awoke with the feeling which was becoming commonplace to me now—a mingling of terrible apprehension and excitement. Any hour could bring my deception out into the open, I realized. I should be lucky to survive for a few weeks.

I rose and went down to breakfast. I had an idea that this was taken any time between eight and ten and that one just helped oneself from the sideboard. I went into the room where we had dined the previous night. Yes, the table was set for breakfast and food was sizzling on the sideboard in silver dishes.

I helped myself and sat down, grateful to be alone. I was hungry in spite of the internal uneasiness.

While I was eating Janet looked in.

"Oh, early," she said in that familiar way of hers. "Not like you, Miss Susannah, to be up at this hour. What's happened to you? Changed your habits since abroad? Miss Lie-abed has become Miss Early Bird."

So once again I had slipped. I must remember that.

"I don't suppose Jeff Carleton will be here till ten," she went on. "He won't be expecting you to want to look round the estate with him at this hour, I can tell you. He was saying how glad he was that you were coming home. He says it's a great responsibility to have when he can't get permission for what he wants. Though, mind you, Mr. Esmond gave him more or less a free hand. He says he doesn't expect that from you."

I listened. So this morning I was to go round the estate with Jeff Carleton, the farm manager. I had to thank Janet for giving me plenty of information. I felt quite exhilarated to pick up so much. I was learning to keep my eyes and ears open.

I said: "I'll be ready when he comes. Ten o'clock, you say."

"Well, that was the time you and Mr. Esmond used to go with him, wasn't it?"

"Oh yes," I said.

"He's told Jim to get Blackfriar saddled for you. He's so certain you'll want to go round the estate at once."

I said again: "Oh yes."

"I don't suppose Blackfriar will have forgotten you. They say horses never forget. He was always good with you, though."

There was a warning in this. I felt a momentary qualm. What if the horse rejected me? There was an implication in Janet's words that Blackfriar, though good with Susannah, was inclined to be less so with others.

"I'll leave you to your breakfast," said Janet.

I went up to my room and changed into riding kit. I uttered a prayer of thanksgiving to my father for bringing a couple of horses to the island and to the Halmers for making me ride so often on the property. They were all such expert riders and galloping through the bush with them and trying to keep up with their skill had given me confidence and a certain expertise.

Just after ten o'clock Jeff Carleton arrived at the house. I went down to meet him.

"Well, Miss Susannah," he said, seizing my hand, "it is good to see you back. We'd been hoping you'd come before. This has been a terrible tragedy."

"Yes," I said, "terrible."

"It was all so sudden. Only a week before I was riding round the place with him and Mr. Malcolm and then ... he's gone."

I shook my head.

"Forgive my speaking of it. We've got to go on from there, haven't we, Miss Susannah, and I'm just wondering if you have any ideas about the estate."

"Well, I'd just like to look at things. ..." I wasn't sure whether to call him Jeff, Carleton or Mr. Carleton—so I called him nothing.

"You'll be wanting to take a hand, I reckon," he said with a laugh.

"Oh yes, I suppose so."

We came to the stables. The groom stepped forward and said: "Good day to you, Miss Susannah. I've got Blackfriar ready."

"Thank you." I wished I knew the names of these people. It was a great handicap to be in the dark.

I identified the horse. His name was useful. He was beautiful with his black coat in which were a few white flecks about the neck. His name suited him.

"There's one who will be glad to have you back, Miss Susannah. He was always your horse, Blackfriar was. I'll swear he pined when you went away. Of course he got used to your being away when you were in France."

"That's right," I said.

I was thankful that I had always had a rapport with horses and was able to approach Blackfriar confidently. I patted him cautiously. His ears went back. He was alert.

"Blackfriar," I whispered, "it's Susannah ... come back for you."

There was a tense moment while I was not sure whether he was going to reject me. I patted him and said: "You haven't forgotten. You know me." My voice was soothing. I brought a lump of sugar from my pocket. Susannah had always done that with our horses. They were creatures she was really gentle with.

"That's done it," said the groom. "He remembers that all right."

I leaped into the saddle and, patting him again, murmured: "Good old Blackfriar."

I wasn't sure whether he knew I was not Susannah, but I did know that he liked me; and I felt a sense of triumph as we rode out of the stables.

"Where would you like to go first?" asked Jeff Carleton.

"I'll leave that to you."

"I thought we'd look in at Cringles'."

"Yes," I replied, "if you think that a good idea."

I deliberately allowed him to go ahead. We came into the road which led past the woods and walked our horses side by side.

"You'll find a few changes, Miss Susannah."

"I expect to."

"It's been quite a long time since you were here."

"Quite a long time. Of course there was that short time when I was home after France."

"Yes, and then away again. There'll be certain things you'll be wanting to change possibly."

"I'll have to see."

"You always had ideas about the estate, I know."

I nodded, wondering what ideas Susannah had had.

"Of course we never thought ..."

"Of course not. But these things happen."

"Mr. Malcolm was very interested. He was here about a month ago, I think it was."

"Oh, was he?"

"I think he had ideas ... he being a man of course. When Mr. Esmond died ... he probably thought you wouldn't want to concern yourself with the running of things. I thought to myself, You don't know Miss Susannah!"

I gave a short laugh.

"Of course," went on Jeff Carleton, "with an estate like this people might think if there's a man in the family he should be the one to concern himself with it."

"And you think Malcolm had that notion."

"Sure of it. He thought he might be the next when Esmond died on account of your being a lady, even though he knew, like the rest of us, that your grandfather would hesitate to name him because of that long-ago quarrel."

"Yes," I said.

"Your grandfather's younger brother could, you might say, have a claim on the estate and that claim might go down through his son and grandson. There's some sense in it. Some families don't let the ladies inherit. It's different with Matelands."

"Yes, different with Matelands."

I had at least established Malcolm's claim. He was the grandson of Grandfather Egmont's younger brother. A definite claim. He was the one I was cheating out of his inheritance.

A tremor of alarm ran through me. But it was such a lovely day. The fields were gay with buttercups and daisies; and the birds were going wild with joy because the sun was up there in the sky and spring was advancing into summer.

I couldn't help feeling exhilarated.

"The farms are showing a good profit," went on Jeff Carleton. "All except Cringles'. I don't know what you feel about them and if you could suggest anything."

"Cringles'," I said, as though I were pondering the matter.

"They went to pieces after the tragedy."

"Oh ... yes."

What tragedy was this? I must feel my way with caution.

"The old man has never been the same since. It seems to have hit Jacob more than any of them. Of course Saul was his brother. They were twins, I think ... always closer. Jacob always used to depend on Saul. It was a great blow to him."

"It must have been."

"And the farm has consequently suffered. I suggested taking it away from them. They're not getting the best out of the land. Esmond wouldn't hear of it. He had a kind heart, Mr. Esmond. They all knew they could take their troubles to him. I know you used to get a bit impatient with him at times."

"Yes," I murmured.

"So ... I think they may be expecting changes. There's Granny Bell in the cottages who wants her roof done. It should be attended to. She'll have the rain in if we get any heavy stuff. She was going to ask Esmond to do it, but he was taken ill on the very day I was going to put it before him. So nothing's been done. Would you like to look at the roof?"

"No," I said. "Go ahead and do it."

"It would be wise really. But to get back to Cringles' ..." I looked about me. I could see fields of wheat and in the distance sheep grazing. The farmhouse lay in a valley. "They don't really take care of the property. Saul was the one. He was a good worker, Saul—one of our best. It was a great pity. No one ever seemed to get to the bottom of it."

"No," I said.

"Well, it's past history now. A year or more ... It's time it was forgotten. People do away with themselves at times ... they have their private reasons, and I always say, live your own life and it's not for any of us to judge others. Would you like to see the Cringles?"

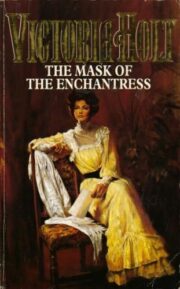

"The Mask of the Enchantress" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Mask of the Enchantress". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Mask of the Enchantress" друзьям в соцсетях.