You must make arrangements to come home at once, Susannah.

My love to you.

Your Aunt Emerald

I read the letters through again and for a long time sat staring into space.

When I looked up I saw that I had been sitting there for half an hour. During that time my thoughts had taken me back. I was standing on the edge of the woods looking at the castle. I was there inside, seeing it clearly from what I had heard from Susannah and my mother.

It was amazing.

I had not thought of my tragic circumstances all that time.

The Great Deception

It is a common human characteristic that when one has decided on a course of action which is wrong, dishonest and even criminal the mind of the offender immediately begins to discover reasons why such action is justifiable.

I was a Mateland. My father's offspring should surely be in the line of inheritance. I was my father's second daughter. Esmond was dead; Susannah was dead. Had my parents been married I should have been the next.

It was no use reminding myself that my parents were not married. I was, as I had frankly been told by the children at school, a bastard; and bastards had no rights.

But, said my persuasive mind, my father had loved my mother more dearly than he had loved anyone else. She was his wife in his eyes. I was a Mateland. I had changed my name when I came to them; surely I was entitled to be recognized as such.

The idea was growing.

But for Susannah, Philip would be with me now. He would have accompanied me to his sister's wedding, and we should have married, for he had been in love with me to a certain extent, as I had been with him.

But Susannah had come and stolen my lover. Why should I not take her inheritance? There! It was out.

"It's fantastic," I said aloud. "It's impossible. It's a wild dream."

And the alternative?

I stared the bleak future blankly in the face. I could go to Roston, Evans; I could confess my little deception. It was nothing very serious at the moment. Then I could go to the Halmers and stay with Mrs. Halmer until I worked out what I was going to do. Perhaps I could borrow the money to go to England and there try some post as a governess or a companion, which seemed to be the only course open to women of some education who suddenly found themselves forced to earn a living. I should be utterly miserable.

On the other hand there was this wild preposterous plan which had presented itself to me. All sorts of notions, ideas, possibilities were thrusting themselves into my mind.

It's wrong, I kept telling myself. It's fraud. It's criminal. It's unthinkable.

In some ways to contemplate it acted as a palliative. It took my mind off misery. Of course I won't do it, I told myself, but it would be interesting to see how it could be done ... if it could be done.

An hour slipped by. I was still thinking of it.

I could go to Roston, Evans. The young man did not know me. He was, in fact, of the opinion that I was Susannah. His accosting me in the street had been the beginning of it all. It would never have occurred to me if that had not happened. It was Fate tempting me. It was like a bait. I had taken the first step down the slippery slope when I allowed him to believe I was Susannah. Why had I done that? It was like some prearranged pattern beginning to show itself.

The first part would be easy. I could go to Mr. Roston and get the money for my passage home. I could tell him that I had set out for the island and been unable to land because of the volcanic eruption. That was all true.

I could go to England ... and to Mateland Castle. Then the dangerous part would begin.

One part of Emerald's letter kept coming into my mind: "I shall hardly know what you look like. It has been so long."

Surely it was meant to be!

I thought a great deal about the castle. I believed I knew something about Emerald from what Anabel as well as Susannah had told me. She had said it was long since we met; she referred to her poor vision. That letter of hers was like a beckoning finger, like Fate saying: Come on. It is all made easy for you.

Esmond was the only one who would have been so acutely aware of everything about Susannah that he would immediately recognize an imposture. And Esmond was dead.

Well, it had been diverting to dream and to fabricate such a wild adventure in my mind; and God knew I was in need of some divertissement to draw me out of this hideous depression which enveloped me.

I had done nothing so far except allow Roston to believe that I was Susannah, collect her mail and open it. There was nothing very wicked about that.

I must leave it there and start thinking sensibly.

Misery enveloped me. I kept seeing Anabel coming to visit me at Crabtree Cottage, carrying me off with her on that never-to-be-forgotten night—and most vividly of all, holding my hand as we stood together looking at the castle.

I had no desire to go on living unless ... unless ...

I spent a restless night. I kept dozing and dreaming that I had come to the castle.

"It is mine now," I said in my dream.

Then I would awake and toss from side to side, my dream still with me.

In the morning the first thing I thought was: Mr. Roston will be looking for Susannah. He will think she was not on the island. He will know by now that she is the owner of the castle and that that was the purport of the letters he gave me. He would be expecting her to call. I had already created a situation. I had forgotten that. Yes, I was deeper in this than I had at first thought.

Instead of filling me with horror, this thought exhilarated me.

Matelands lived dangerously and I was one of them.

Then I knew that I was going to attempt this outrageous adventure. I was going to enter the biggest masquerade I had ever envisaged. I knew it was wrong. I knew that I would be in acute danger. But I was going to do it. I had to do it. It was the only way out of the slough of despond.

The fact was that I didn't care what became of me. The Grumbling Giant had, at one stroke, robbed me of everything I cared for.

I was going to do this desperate thing because, for a host of reasons, it would give me an interest in life.

Besides, I wanted the castle. From the moment I saw it I had felt bound to it, and the urge to take it was growing stronger with every hour because it was only that which could make me want to go on living.

As I walked down Hunter Street I was turning over in my mind what I would say to Mr. Roston, and even as I entered the building and started up the stairs, my mind was not entirely made up. I should not have been surprised if I had blurted out the truth about my deception. But when he received me in his office I did no such thing. He began by saying:

"Miss Mateland, I am glad you've come. I have been expecting you. This is a terrible matter. Of course there was always the possibility of the volcano's erupting, but no one thought it likely, or my father would have advised you against going in the first place. It must have been a shock to you. And now ... this even greater shock. The death of your cousin in England." "I ... I can't believe it. It's quite terrible." "Of course. Of course. I gather it was a sudden illness. Most unexpected. A dreadful blow for you." He was gently soothing but, I sensed, eager to get on with the real business. "I suppose you will be returning to England." "It's what I must do. I haven't enough money for my passage... ."

"My dear Miss Mateland, that presents no problem. We have instructions from Carruthers, Gentle. I can advance you as much as you need. We can book your passage. I hear that your auntis eagerly awaiting your return."

My resolution was weakening. "The old Debil" was indeed at my elbow.

I suddenly knew, there in Mr. Roston's office, that I was going on with it.

Within three weeks I was sailing to England on the S.S. Victoria. My thoughts went back to that journey I had made with my parents over eleven years before. How different that had been and yet both voyages were dominated by a sense of adventure and excitement. In both instances I was going into a new life.

There was something uncanny about this. I was changing my character. At times I had the strange feeling that I was becoming Susannah. There was a new ruthlessness about me. Was it possible that when someone died that person's soul could find refuge in someone else's body? There was a theory about that, I believed. Sometimes I felt that Susannah had entered mine.

Mr. Roston had given me a trunk of clothes and documents which she had left in the care of his firm. Before leaving Sydney I had gone through it. I had tried on the dresses and chic hats. They all fitted me. I began to walk like Susannah. I began to talk as she had. The girl I had been would never have dared do what I was doing. It was significant that I had ceased to make excuses for myself.

I was a Mateland; I was Susannah's sister; I belonged to the castle. Why should I not take over the role of Susannah? What harm could it do? Susannah was dead. It meant changing my Christian name from Suewellyn to Susannah. They even sounded something alike.

S.M. was imprinted on the trunks. My own initials.

The long sea voyage gave me the time I needed to adjust and to observe the change in myself. People noticed me. I had lost all my diffidence. I had become not only an attractive young woman but one who knew she was.

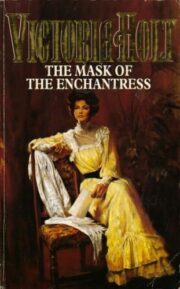

"The Mask of the Enchantress" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Mask of the Enchantress". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Mask of the Enchantress" друзьям в соцсетях.