"Yes, I can."

"And you were hidden away, weren't you? And I suppose on the night my father killed Uncle David they swooped down and carried you away with them to this desert island. What exciting lives we Matelands live, don't we?"

"This one's could hardly be described as such."

"Poor Suewellyn, we must alter that. We must make your life more amusing."

"I dare say you are the sort of person exciting things happen to."

"Only because I make them. I must show you how to make them happen to you, little sister."

"Not so little," I retorted.

"Younger. How much by? Do you know?"

We compared birthdays. "Ah, I am the senior," she said. "So I may call you little sister justifiably. So you were tucked away, were you? And Anabel used to visit you. It must have been a fearful quarrel they had that night. I shall never forget waking in the morning and feeling that something had happened. There was a terrible hush over the castle and the nurses refused to answer my questions. I kept asking where my father was. What had happened to my Uncle David? And my mother was just lying there on her bed as though she were dead like my uncle. It was a long time before I learned what had happened. They never tell children things, do they? They don't understand that what you can imagine might be far worse than what actually happened."

"There could hardly be a greater tragedy."

"You knew, did you? I suppose they told you. I suppose you know why."

"They will tell you if they think you should know," I said and she burst out laughing.

"You are a very self-righteous little sister. I dare say you always do what is right and honorable, don't you?"

"I shouldn't think so."

"Nor should I... if you are a Mateland. But imagine what it felt like having a murderer for a father. Though, of course, I didn't know this until later. I had to find out myself ... listening at doors. Servants are always chartering. 'Where is my father? Why isn't he here any more?' I was always asking, and they would button up their lips, and I knew by their eyes that they longed to tell me. And there was no one in the doctor's house and all the poor patients were sent away empty. And my mother, of course ... she was always ill. She would tell me nothing. If I mentioned my father to her she would just get tearful. But I got it out of Garth. He knew everything and he couldn't keep it to himself. He told me I was the daughter of a murderer. I've never forgotten that. I think he found some satisfaction in telling me. He said his mother hated me because my father had killed Uncle David."

She turned to me and laid her hand on my arm.

"I'm talking a great deal," she said. "I always do. But we'll have lots of time for talk, shan't we? There's so much I want to tell you ... so much I want to know about you. Dinner is in an hour, Anabel said."

"Shall I help you unpack?"

"Oh, I shall just drag something out of the bag and change now. Do you think the malevolent black woman could bring me some hot water?"

"I'll have it sent up."

"Tell her not to put a spell on it. She looks as though she brews them."

"She's quite benevolent really. It's only if you offend them that you have to take care. I'll have the hot water sent up and shall I come to you when dinner is ready?"

"That would be lovely, little sister."

I went out of her room and it was some time later when I remembered that mail had come with the boat and that there was a letter from Laura waiting for me.

Even as I slit the envelope my thoughts were full of Susannah.

My dear Suewellyn [I read],

It has happened at last. The wedding is to be in September. This will fit in just right for the boat. You can arrive a week before and help with the preparations. It is so exciting. My mother wants a grand wedding. The boys pretend they don't and it's a lot of nonsense. But I think they are thrilled really.

I'm having a white gown made. The bridesmaids' dresses are going to be pale blue. You are to be a bridesmaid. I shall have the dresses made up to a point and all they will need is a quick fitting when you come. I am writing to Philip too. You can travel together. Oh, Suewellyn, I'm so happy. I beat you to the post, didn't I? ...

I put the letter away. On the boat's next call I should be ready to leave with it. Philip could come with me. It might be that Laura's wedding would make him think that I was almost as grown up as his sister and that it was time I married too.

I was smiling to myself. It was all falling so naturally into place—or had been.

I had a feeling that things might change now that Susannah had come.

They did. Her very presence changed the place. There was a great deal of excitement on the island because of her. The girls and women chattered together about her and giggled as we passed by. The men followed her with their eyes.

Susannah enjoyed their interest. She was clearly delighted to be on the island.

She was charming, affable and affectionate; and yet her presence had an effect on us which was the reverse of comforting. ... I knew that she reminded Anabel of Jessamy and that disturbed her peace of mind. She was as conscious now of the wrong she had done Jessamy as she had been in the beginning.

"My poor Mama," Susannah said, "she was always so sad. Janet... do you remember Janet? Janet said she had no will to live. Janet was impatient. What's done's done,' she used to say. 'No use crying over spilled milk.' As if losing your husband and your best friend could be compared with knocking over the milk jug!" Susannah's laugh rang out as she recalled Janet and gave what I believe was a fair imitation of her. But, amusing as it might be, it brought back bitter memories to Anabel.

And my father? "A new doctor came to Mateland. People went on talking about you for years. ... It was a nine days' wonder, wasn't it? Poor Grandfather Egmont. He used to go about saying, I've lost both my sons at a stroke.' He made a great fuss of Esmond after a while and he invited Malcolm to stay more often. We wondered whether Malcolm would be the next in line of succession. We weren't sure because Grandfather Egmont had always borne a grudge against Malcolm's grandfather. He was always rather fond of me and some people thought I'd be the next if Esmond didn't have children. He was always rather fond of girls ... liked them a lot better than he liked boys... ." She laughed. "It's a family trait in the males which has persisted through the centuries. He seemed to realize that girls might have other attributes than good looks and charm. He used to go round the estate with me and show me things and talk to me about it. He used to say there was nothing like having two strings to your bow. Garth used to call Esmond, Malcolm and me the Three Strings."

Somehow in her seemingly lighthearted conversation she found the spot where best to thrust the barb, and when it came there would be an expression of such innocence on her face that no one could believe that she was aware of what she was doing.

She showed a great interest in the hospital but somehow managed to belittle it. It was wonderful to have such a place on a desert island, she said. It could have been part of a real hospital, couldn't it? They would have to train those black people to be nurses, she supposed. How very intriguing!

She made it all seem like a bit of play acting; and I noticed that there was a change in Philip now. He no longer had that exalted expression on his face when he talked about the work they were going to do.

I wondered whether even my father had begun to think of this project as a wild dream.

Anabel and I sat together in our favorite spot under the palm trees in the shadow of the Grumbling Giant, and as we looked over the pearly blue-green translucent sea and listened to the gentle breaking of the waves on the shore, Anabel said: "I wish Susannah hadn't come."

I was silent. I could not really agree because Susannah excited me. Things had changed since she came and, although I knew they had not done so in the most comfortable manner, I was completely fascinated by my half sister.

"I suppose really," said Anabel, "I'm being unfair. It's natural that she should bring back memories of things we would rather forget. One should not blame her. It's just that she makes us blame ourselves."

I said: "It's so strange to me ... exciting in a way. Sometimes I feel I am looking at myself."

"The resemblance is not all that marked. Your features are alike. I remember her as a little girl. She was ... mischievous. One doesn't take much notice of that in children. Oh, as I say, I'm being unfair."

"She is very pleasant to us all," I said. "I think she does want us to like her."

"Some people are like that. They supposedly mean no harm ... and in fact do nothing one can point a finger to, but they act as a disturbance to others while seeming innocent of this. We have all changed subtly since she came."

I thought a good deal about that. It was true in a way. My mother had lost her exuberant good spirits; she was thinking a great deal about Jessamy, I knew. My father was living in the past too. It had been a terrible burden to carry, the death of his own brother. He would never need to be reminded of what he had done but he had begun to work out his salvation and he had dedicated himself to saving lives. And now his guilt sat heavily upon him. Moreover somehow the hospital had been belittled. It seemed like a childish game instead of a great endeavor.

Philip had changed too. I did not want to think about Philip. I had believed that he was beginning to love me. When I first went to the property as his sister's friend I had been just a schoolgirl to him. We had enjoyed being together, had talked together and liked the same things. I had been entranced by everything I saw and he had enjoyed introducing me to the great outback. But he had had to get used to the idea that I was growing up. I thought he had when he came to the island. I had, perhaps conceitedly, thought that I was one of the reasons for his coming. My parents had thought so too. We had all been so happy and cozy. The nightmare of that fearful experience that my parents had undergone had receded, although it could never disappear altogether. Now of course it was right over them, brought by Susannah. She could hardly be blamed for that, except that she made it seem as though it had happened yesterday. But Philip? How had she changed him? The fact was that she had bemused him.

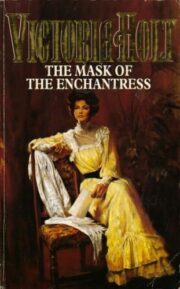

"The Mask of the Enchantress" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Mask of the Enchantress". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Mask of the Enchantress" друзьям в соцсетях.