"I telled Master Luke," mourned Cougaba. "I said, 'No sleep in Master's big bed for whole month. Dance of the Masks to be at new moon.' And Master Luke he laugh and say, 'Not for me and you. Do as I say, Cougaba.' I tell him of Grumbling Giant and he laugh and laugh. Then I sleep in bed. Then the night of the Mask Dance and I stay in Master Luke bed and then ... I am with child. All say, 'Ah, this child of Giant, Cougaba honored lady. Giant came to her. But it was not Giant. ... It was Master Luke and if they know ... they kill me. So Master Luke he say, 'Let them think Giant father of child,' and he laugh and laugh. Cougabel not child of the Mask. And now I frighten. I think Giant very angry with me."

"You mustn't be afraid," said my mother. "The Giant will understand that it was not your fault."

"He take her. I know he take her. He stretch out his hand and draw her down ... down to the burning stones where she burn forever. He say, "Wicked Cougaba. Your child mine, you say. Now she be mine.'"

There was nothing we could do to comfort Cougaba. She kept moaning: "Dat old man Debil was at my elbow, tempting me. I'se wicked. I'se sinned. I told the big lie and the Giant is angry."

My mother warned her to say nothing of this to anyone and that was a relief to poor Cougaba and something she was ready to listen to. I had seen the natives benign since they had accepted my father as an emissary of the great Giant, but I wondered what they would be like if they turned against us. And what Cougaba had done would certainly be considered an unforgivable sin in their eyes.

That night Cougabel was found. My father discovered her on the mountain. She had broken her leg and was unable to walk.

He carried her back to the house and set her leg. The islanders looked on in wonder. Then he made her lie down and would not let her move.

I sat with her and read to her and Cougaba made all sorts of potions for her distilled from plants, for she had great skill in these matters.

Cougabel told me she had gone to the mountain to ask the Giant to stop my going away and then she had fallen and hurt herself. She took this as a sign that the Giant wanted me to go and was punishing her for doubting the wisdom of his wishes.

We accepted that explanation.

Cougaba said no more about the deception she had practiced concerning her daughter's birth. The Giant could not be very angry, my mother told her, because he had merely broken Cougabel's leg, and my father had said that as her bones were young and strong he could mend her leg and none would guess it had ever been broken.

So the days before my departure were spent mostly with Cougabel and when the time came for me to go she was calm and resigned.

My father was very sad at our going but I knew he thought it was the right thing to do.

So we came to Sydney, my mother and I, and my delight in the beautiful harbor and perhaps my even more intense enchantment by the big city—for I was accustomed to scenic beauty-reconciled me to this new phase in my life. I was excited by all the people. I loved the streets, which wound about in a haphazard way because they had grown from the cart tracks of earlier days. I loved the big streets best and in a few days I knew my way about. I shopped with my mother in the great shops such as I had never seen before. I had never realized there was so much merchandise to be bought.

We should have to buy clothes for my school, said my mother, when we were in the room in our hotel. "First though," she added, "we must find the school."

My mother made inquiries and we looked at three before we decided on one. It was not far from the harbor, right in the heart of the town. My mother saw the headmistress and explained that we had lived on a Pacific island and she had taught me until now. I was given tests from which I was glad to say I emerged in some triumph, so my mother had been a good teacher. Then it was arranged that I should become a boarder at the start of the term, which would give my mother time to leave me at school and catch the next ship back to Vulcan Island.

What weeks they were! We shopped madly. I knew the names of the streets and how to find them. We were able to buy my school uniform in Elizabeth Street. The headmistress had told us where to go. We bought clothes and stores and drugs to be sent to the ship en route for Vulcan Island; and when we had done our shopping we took great pleasure in exploring the town, watching the ships which came into the harbor, visiting the spot where Captain Cook had landed; and I felt I was a child again going with Anabel on a jaunt after she had picked me up from Crabtree Cottage.

Then the day came when I was taken to my school and we said good-by to each other. I was desperately unhappy and missed my parents and the island so much.

Then as the weeks passed I settled in. My strangeness was an attraction. The girls would listen for hours to stories of the island. I was an oddity and as I was bright and able to stand up for myself I began to enjoy school.

By Christmas when I returned to the island I had changed. Everything had changed. Cougabel was better and her leg showed no sign that it had been broken. Another triumph for my father!

But she was no longer a suitable companion for me. She was just an islander and I had been out into the big world.

I questioned a great deal now. What were we doing here? My mother had talked to me and made allusions to the past but she had always been able to brush aside awkward questions. She could do so no longer. I was getting curious. I wanted to know why we must live our lives on a remote island when there were towns like Sydney, when there was a whole world to explore.

I remembered the castle I had seen years ago. It had always held a magical quality for me. Now I became obsessed by it and there was so much I wanted to know. School had aroused me from my lazy indifference to the past. I was consumed by a desire to know what it was all about.

That was why my mother had decided to write it all down to tell me.

When I next returned for my holidays she showed me her account of what had happened and I read it avidly. I understood. I was not shocked to learn that I was a bastard and that my father was a murderer. I wondered a great deal about what had happened after my father left. I thought of Esmond and Susannah. They were the ones who interested me. I wondered if I should ever see them and I was filled with a desire to go to that magic castle and find them.

The Dance of the Masks

I was at school for two years and was past sixteen when it was decided that I should leave and go back to the island. In the meantime I had made the acquaintance of the Halmers. At school Laura Halmer and I had become close friends. She had been drawn to me at first by the strangeness of my unusual background and had been an avid listener to tales of the island. I had been attracted by her sophistication. She knew Sydney well and the shops were her happy hunting ground. Her family were farmers and owned a large estate to which they always referred as "the property." This property was some fifty miles north of Sydney. Laura, as the youngest of a family of brothers, was somewhat indulged and it was natural that during my second term at school she should suggest that I go home with her for the half-term holiday, which was just one week and thus not long enough for me to go back to the island. This I was glad to do.

At the Halmers' I was in yet another world. I was received with warmth into the family as a friend of Laura's and in a few days I felt as though I had known them for years. The property was an exciting place to be as there were so many activities going on. They were up at dawn and the Halmer men would be out early and come in at eight o'clock for a breakfast of steak or chops. There were many hands about the place, all with their various duties to perform. It was a very big property.

There I first met Philip Halmer. He was the youngest of Laura's three brothers. The two elder ones were big bronzed men and I could not tell one from the other during those first days. They talked of sheep constantly, for sheep were the main business of the property; they laughed a great deal; they ate a great deal; and they accepted me as one of them since I was a friend of Laura.

With Philip it was different. He was about twenty at that time. He was the clever one, his mother told me. He had soft fair hair and blue eyes; he was sensitive and when I discovered that he was training as a doctor I was immediately drawn to him. I explained that my father had gone to the island to study tropical diseases and that he hoped to build a hospital there. I was very enthusiastic about my father's work and Philip and I were often together talking about the island. It made a special bond between us.

During that mid-term week I spent at the Halmers' I learned a great deal about life in the bush. We would ride out, Laura, Philip and I, and make a campfire in the bush where we brewed tea in a billycan and ate dampers and johnnycakes; and few things had ever tasted so good. Philip used to tell me about the trees and foliage, and I was fascinated by the tall eucalypts, whose branches could fall so swiftly and silently from their great height that they could impale a man, and so they had earned the name of widow-makers. I saw trees and earth scorched by the terrible forest fires and I heard of all the plagues which could beset settlers in this sometimes unwelcoming land.

So after that short week at the Halmers' another change had come into my life.

I went back to school and then Christmas was looming.

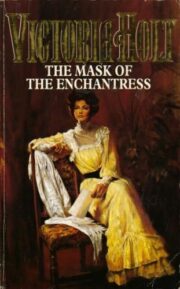

"The Mask of the Enchantress" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Mask of the Enchantress". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Mask of the Enchantress" друзьям в соцсетях.