I shall never forget the first Feast of the Masks following our arrival. Everyone was behaving in a very odd way. They averted their eyes when we were near. Cougaba was worried. She kept shaking her head and saying: "Giant angry. Giant very angry."

Cougabel was a little more explicit. "Giant angry with you," she said; and her bright eyes were frightened. She put her arms about me. "No want you die," she said.

I forgot that for a while but one night I awoke remembering it and I thought of the stories I had heard about men being thrown into the crater to pacify the Giant. It was through Cougabel that I realized our danger.

"Giant angry," Cougabel explained. "Mask coming. He will show on Night of Masks."

"You mean he will tell you why he is angry?"

"He is angry because he want no medicine man. Wandalo medicine man. Not white man."

I told my parents.

My father retorted that they were a lot of savages. They should be grateful to him. He had heard that a woman had died of some fever only that day. "If she had come to me instead of going to that old fool of a witch doctor she might be alive today," he said.

"I think you should open up the plantation," my mother put in. "That's what they want."

"Let them do it themselves. I know nothing of coconuts."

The bamboo drums started. They went on all day.

"I don't like them," said my mother. "They sound ominous."

Cougaba went about the house refusing to look at us. Cougabel put her arms round me and burst into tears.

They were warning us, I knew.

We could hear the drums beating; we could see the light from the fires and smell the flesh of the pig. All through the night my parents sat at the window. My father had his gun across his knees. They kept me with them. I dozed and dreamed of frightening masks; then I would wake and listen to the silence, for the drums had stopped beating.

The silence persisted into the next morning.

Later that day a strange thing happened. A woman came to the house in great distress. I had had her pointed out to me as one who had given birth to a child who had been conceived at the last Dance of the Masks. Therefore it was a special child.

The boy was ill. Wandalo had said he would die because the Giant was angry. As a last resort the mother had brought the child to the white medicine man.

My father took the child into the house. A room was prepared for him. He was put to bed and his mother was to stay with him.

Soon the news of what had happened spread and the islanders came to gather about the house.

My father was excited. He said the boy was suffering from marsh fever, and if he had come in time he could save him.

We all knew that our fate hung on that child's life. If he died they would probably kill us—at best drive us from the island.

My father said exultantly to my mother: "He's responding. I might save him. If I do, Anabel, I'll start their plantation. Yes, I will. I know nothing about the business but I'll find out."

We were up all that night. I looked from my window and saw the people sitting there. They had flaming torches. Cougaba said that if the boy died they would set fire to our house.

My father had taken a terrible risk in bringing the boy here. But he was a man to take risks. My mother was such another. So was I, I discovered later.

In the morning the fever had abated. All through the next day the boy's condition improved and by the end of the day it was clear that his life had been saved.

His mother knelt down and kissed my father's feet. He made her get up and take the child away. He gave her some medicine which she gratefully took.

I shall never forget that moment. She came walking out of the house holding the child and there was no need for anyone to ask what the outcome was. It was clear from her face.

People rushed round her. They touched the child wonderingly and they turned to stare in awe at my father.

He raised his hand and spoke to them.

"The boy will get well and strong. I may be able to cure others among you. I want you to come to me when you are sick. I may cure you. I may not. It will depend on how ill you are. I want to help you all. I want to drive the fever away. I am going to start up the plantation again. You will have to work hard for I have much to learn."

There was a deep silence. Then they turned to each other and put their noses together, which I think was a form of congratulation. My father went into the house.

"And to think that was all due to five grains of calomel, the same of a compound of colocynth and of powder of scammony and a few drops of quinine," he said.

No child had been conceived on that Night of the Masks. It was a sign, said the islanders. The Giant had considered them unworthy. He had sent them his friend, the white medicine man, and they had failed to give him honor.

The white man had saved the Giant's child and, because the Giant was pleased at that and because they had performed the Dance of the Masks, he had asked their friend to start up the plantation again.

The island would prosper as long as it continued to pay homage to the Giant.

My father now dominated the island. He became known as Daddajo and my mother was Mamabel. I was known as Little Missy, or the Little White One. We were accepted.

True to his word, my father set about getting the industry of the island working again and because of his immense energy it did not take long. The islanders were wild with happiness. Daddajo was undoubtedly the emissary of the Grumbling Giant and was going to make them rich.

My father immediately started a nursery for coconuts. He had found books on the subject which had been left behind by Luke Carter and they provided him with certain necessary information. He selected a piece of land and placed on it four hundred ripe nuts. The islanders buzzed round in excitement, telling him what to do, but he was going according to the book and when they saw this they were overcome with respect, for he was doing exactly what Luke Carter had done. The nuts were covered with sand, seaweed and soft mud from the beach, one inch thick.

My father had appointed two men to water them daily. They were on no account to neglect to do this, he said, glancing at the mountain.

"No, no, Daddajo," they cried. "No ... no ... we no forget."

"It had better be so." My father was never averse to using the mountain as a threat when he wished to get something done, and it worked admirably now that they were convinced that he was the friend and servant of the Giant.

It was April when the nuts were placed in the square and they must be planted out, said my father, before the September rains came. All watched this operation presided over by my father, chattering together as they did so, nodding their heads and rubbing noses. They were obviously delighted.

The plants were then set in holes two or three feet deep and twenty feet apart and their roots were bedded with soft mud and seaweed. The waterers must continue with their task for two or three years, my father warned, and the new trees must be protected from the glare of a burning sun.

They plaited fronds of palm which they used to shelter the young trees. It would take five or six years before these trees bore fruit, but meanwhile work would progress with those which were already mature and which abounded on the island.

The nursery was a source of delight. It was regarded as an indication that prosperity was coming back to the island. The Grumbling Giant was not displeased with them. Far from sending out his wrath, he had given them Daddajo to take the place of Luke Carter, who had grown old and not caring, so that everyone neglected his or her work and consequently benefits no longer came to the island.

My father applied great enthusiasm to the project. They accepted him now as the doctor, but he needed a further outlet for his tremendous energy and this supplied it. I see now that both he and my mother were restless. Often their thoughts turned to England. They were shut away from the civilized world and only made contact with it when the ship came in every two months. At first they had sought a refuge, somewhere to hide away and be together. They had found it and, having won a certain security, they were remembering what they were missing. It was only human to do so.

So the coconut project offered a great deal to them both. They became absorbed in it. There was a new mood on the island. There were soon goods to be sent back to Sydney. There was an agent who came to see my father and who was to arrange for the selling of the goods which were produced. Cowrie shells were used as currency on the island. My father paid the natives in these. It was amazing how contented the people were now they had something to do. Instead of a couple of women sitting together idly plaiting a basket under a tree as it had been when we came, there were now groups of them seated on platforms open at the sides but protected by a covering of thatch from the sun; these my father had ordered to be constructed; and in them the women would make baskets and fans and ropes and brushes with the external fiber. My father had also turned some of the round huts into a factory for producing coconut oil.

Life had changed since we came. It was now as it had been in the days of Luke Carter when he had been a young and energetic man.

My father set overseers to look after the various activities, and these overseers were the proudest men on the island. It was amusing to see them strut about, and it became the ambition of every man to be an overseer.

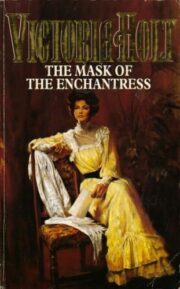

"The Mask of the Enchantress" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Mask of the Enchantress". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Mask of the Enchantress" друзьям в соцсетях.