I discovered a great deal from Cougabel. She took me with her to lay shells and cocks' feathers on the mountainside.

"You come too," she said. "Perhaps Giant angry with you. You come to island and Wandalo not pleased. He say medicine man here. Want man to sell rope and baskets and coconut oil... . Don't want medicine man."

I replied: "My father is a doctor. He is not here to work with coconuts."

"You take shells for Giant," she said, nodding sagely as though it would be wise for me to follow her advice.

So I did.

"The Giant can be terrible angry. Grumble ... grumble ... grumble. ... He throw out burning stones. 1 very angry,' he say."

"It's what is called a volcano," I told her. "There are others in the world. It's quite natural."

The English of Cougaba and Cougabel was better than that of most of the people. They had lived in the big house for a long time. All the same it left much to be desired. Cougaba was expressive in her gestures, though, and we could understand her very well.

"He warns," she told us. "He say, 1 angry.' Then we take shells and flowers. When I was little girl, like you, missy, they throwed man in the crater. He was one wicked one. He killed his father. So they throw him in ... but Giant not please. He did not want bad man sacrifice. He want good man. So they took holy man and throw him in. But old Giant still angry. You watch old Giant. He finish all island once."

I used to try to explain to her that it was a perfectly natural phenomenon. She would listen gravely, nodding. But I knew she did not understand a word of what I said and wouldn't have believed it if she had.

Slowly I absorbed the lore of the island from my parents, from Cougaba and Cougabel and from the magician Wandalo, who showed no objection when I went and sat beside him under the banyan tree.

He was very small and thin and wore only a loincloth. I was fascinated by the way in which his ribs stood out. To look at him was like looking at a skeleton. He had a little round hut at the edge of a clearing among the trees and there he would sit all day with his magic stick making lines in the sand.

The first time I saw him was just after Luke Carter had left and my mother's fears had abated a little and I was allowed to go out on my own as long as I did not stray too far from the house.

I stood at the edge of the clearing watching Wandalo, for he fascinated me. He saw me and just as I was about to run away beckoned. I went to him slowly, fascinated yet apprehensive.

"Sit down, small one," he said.

I sat.

"You pry and peep," he said.

"It's just that I was fascinated by you."

He did not understand but he nodded.

"You come from far over sea."

"Oh yes." I told him about Crabtree Cottage and how we came on a ship, while he listened attentively, understanding some of it, I believed.

"No medicine man wanted... . Man for plantation... . Understand, small one?"

I told him that I did and explained as I had to Cougaba that my father was not a businessman but a doctor.

"No medicine man wanted," he repeated firmly. "Plantation man. People poor. Make people rich. No medicine man."

"People have to do what they do best," I pointed out.

Wandalo drew circles in the sand.

"No medicine man." He brought the stick down on the circle he had drawn and disturbed the sand. "No good come... . Medicine man go. ... Plantation man come."

It was very disturbing and difficult to understand, but there was something ominous about Wandalo's actions and words.

Cougabel and I played together. It was good to have a companion. She came to the lessons which my mother gave to me and Cougaba was absolutely overcome with joy to see her little daughter sitting beside me holding a pencil and making signs on a slate. She was a very bright little girl and different from the others on the island with her light chocolate-colored skin. Most of the islanders were a very dark brown, many black. Very soon we were going everywhere together; she was sure-footed and knew which fruits could be safely eaten; she was a happy child and I was glad of her company. She showed me how to cut our fingers with shells and mingle our blood. "We good sisters now," she said.

I sensed that my parents were not as happy as they had hoped to be. In the first place there were the visits of the ships and a few days before they were due to arrive I would be aware of their uneasiness. When the ship left we would be gloriously happy. I used to sit with them and listen to their talking. I would be on a stool leaning against my mother's knee and she would run her fingers through my hair as she loved to do.

I knew that my father had come here to study the malaria, ague, marsh and jungle fevers which abounded. He wanted to see if he could wipe those diseases out of the island. He planned in time to build a hospital.

He said once: "I want to save life, Anabel. I want to make up------"

She said quickly: "You have saved many lives, Joel. You will save many more. You must not brood. It had to be."

I wanted to do something. I wanted to show my love for them and how grateful I was to have been taken away from Crabtree Cottage.

In a way I did have a hand in molding the future and, looking back now, I wonder what might have happened if I had not discovered, through my friendship with these people, what was really going on.

We must have been on the island about six months when the Giant started grumbling.

One of the women heard the rumble when she went to lay a tribute on the lower slopes. It had been an angry rumble. The Giant was not pleased. The rumor spread. I could see the fear in Cougaba's eyes.

"Old Giant grumbling," she said to me. "Old Giant not pleased."

I went to see Wandalo. He was sitting with his stick making very rapid circles in the sand.

"Go away," he said to me. "No time. Giant grumbles. Giant angry. Medicine man not wanted here, says Giant. Want plantation man."

I ran away.

Cougaba was preparing the fish she was going to cook.

She shook her head at me: "Little missy ... big trouble coming. Giant grumbling. Dance of the Masks coming soon."

I gradually learned what was meant by the Dance of the Masks—a little from Cougaba, a little more from Cougabel, and I heard my parents discussing what they had discovered.

For hundreds of years, ever since there had been people on Vulcan, there had been these Dances of the Masks. The custom was practiced on Vulcan Island and nowhere else in the world; and the dance was performed when the grumbling was growing ominous and the shells and flowers did not seem to placate any more.

The holy man—now Wandalo—would take his magic stick and make signs. The god of the mountain would instruct him when the Feast of the Masks should be held. It was always at the time of a new moon because the Giant wanted the rites performed in darkness. When the night was decided, the preparations would begin and go on while the old moon was waning. Masks could be made of anything suitable but they were chiefly of clay and they must completely hide the face of the wearer. Hair was sometimes dyed red with the juice of the dragon tree. Then the feast would be prepared. There were vats of kava and arrack, which was the fermented juice of the palm. There would be fish, turtle, wild pig and fowls, all of which would be cooked on great fires in the clearing where Wandalo had his dwelling. The night would be lighted only by the stars and the fires by which the food was cooked.

Everyone participating in the dance must be under thirty years of age and they must be so completely masked that none knew who they were.

All through the preceding day the drums would be beating, quietly at first... and going on throughout the night. The drum beaters must not slumber. If they did the Giant would be angry. All through the feasting they would continue to beat and, when that was over, the drums, which had been growing louder and louder, would reach a crescendo. That was the signal for the dance to begin.

I did not see the Dance of the Masks until I was much older and I shall never forget the gyrations and contortions of those brown bodies shining with coconut oil, with which they anointed themselves. The erotic movements were calculated to arouse the participants to a frenzy. This was tribute to the god of fertility, who was their god, the Giant of the mountain.

As the dance went on, two by two the couples would disappear into the woods. Some sank where they were, unable to go farther. And that night each of the young women would lie down with a lover, and neither male nor female would know with whom he or she had cohabited that night

It was a simple matter to discover who had conceived, for intercourse between all men and women had been forbidden for a whole moon before. The reason for Cougabel's importance was that she had been conceived on the Night of the Masks.

The belief was that the Grumbling Giant had entered the most worthy of the men and had chosen the woman who was to bear his child; so any woman who had a child nine months from the Night of the Masks was considered to have been blessed by the Grumbling Giant. The Giant was not always lavish with his favors. If not one child was conceived it was a sign that he was angry. There was often no child of that night. Some of the girls were afraid and fear made them barren for, Cougaba told me later, the Giant would not want to bestow his favor on a coward. If there was no child of the night, there would have to be a very special sacrifice.

Cougaba remembered one occasion when a man climbed to the very edge of the crater. He had meant to throw in some shells but the Giant had reached up and caught him. That man was never seen again.

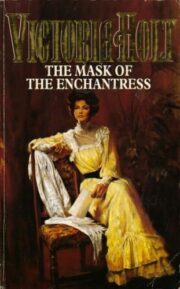

"The Mask of the Enchantress" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Mask of the Enchantress". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Mask of the Enchantress" друзьям в соцсетях.