"Joel ... no!"

"You're coming with me. We'll have to get out of the country."

"Now ..."

"Now ... tonight. We've got to think carefully. It is not impossible. I can arrange with my bank when we are well away.

We can take valuables with us ... everything we can lay our hands on and conveniently take. Go to your room. Get what you can together. Don't let anyone know what you are doing. We'll be well away by morning. We'll ride out a few miles and then get the train to Southampton. We'll get a ship and go out to ... Australia most likely ... and on from there."

"Joel," I breathed. The ... child."

"Yes," he said. "I've thought of the child. You'll have to go and get her. The three of us will go together."

So I went to my room and within an hour after I had heard that pistol shot I was riding through the night with Joel.

We parted at the railway station. He went to Southampton where I was to join him with you. I had to wait for trains and did not get to you until the following day. You know the rest.

That's my story, Suewellyn. You have come to love us, your father and me, and now that you have heard how it happened you will understand.

The Island

In spite of everything that has happened since that day when my mother came to take me away from Crabtree Cottage, I still remember those years on the island as the happiest of my life. It is still an enchanted place to me, a lost paradise.

Looking back, it is not easy to remember always with clarity. Events become blurred by the years. It seems now that the days were full of sunshine—which I suppose they were except during the rainy season. And how I loved that rain! I used to stand in it and let it fall all over me, drenching me to the skin, soft balmy rain; and then the sun would come out, and the steam would rise from the earth, and I would be dry in a few moments. Each day seemed brimming over with happiness, but of course it was not quite like that. There were times when I sensed a certain fear in my parents. Every time a ship came in during those first years my mother would make a great effort to hide her anxiety from me and my father would sit at the topmost window which overlooked the bay and there would be a gun across his knees.

Then all would be well and when the ship sailed away, having brought us all sorts of exciting packages, we would drink a special wine and we would laugh and be merry. I soon realized that my parents were afraid the ship would bring someone they did not want to see.

When we arrived on the island we were received by Luke Carter, whose house my father had bought. Luke Carter had owned the coconut plantation which had brought a certain prosperity to the island. He told my father that he had been there for twenty years. But he was getting old and wanted to retire. Moreover the industry had faltered during the last years. Markets had dropped off; the people didn't want to work; they wanted to lie in the sun and pay homage to the old Grumbling Giant. He was going to stay, as he said, to show my father the ropes. When the ship left next time it would take him with it.

He was all alone now. He had had a partner who had succumbed to one of the fevers which were prevalent on the island and grew worse during the wet season.

"You're a doctor," he said. "You'll know how to deal with it, I dare say."

My father said that one of the reasons why he had wanted to come to this particular island was because these fevers were endemic here. He believed he could discover ways of treating them.

"You'll be up against old Wandalo," Luke Carter told him. "He runs the place. He decides who is and who is not going to die. He's the witch doctor johnny and great chief. He sits under his banyan tree and contemplates the earth."

During the days which followed Luke Carter took my father round the island.

My mother never let me go out without her. When we did go she held tightly to my hand and I was rather disconcerted to find that the sight of us filled the islanders with mirth, particularly the children, who would have to be slapped on the back to prevent their choking. Sometimes we found them peering in at the windows at us and, if we looked up, they would shoot away as if in fear of their lives.

In the evenings Luke Carter used to talk about the island and the islanders.

"They're intelligent," he told us. "Crafty though, and light-fingered. They're not respecters of property. You want to watch them. They love color and sparkle but they wouldn't know the difference between a diamond and a bit of paste. Treat them well and they'll respond. They'll never forget an insult and they'll never forget a good turn. They're faithful enough if you can get their trust. I've lived with them for twenty years without being clubbed to death or thrown down the crater as a sacrifice to the old Grumbling Giant, so I've done rather well."

"I dare say I'll manage equally well," said my father.

They'll accept you ... in time. Strangers put them on their guard. That's why I thought it best to stay awhile. By the time I leave they will have come to regard you as part of the island life. They're like children. They don't question much. The only thing you have to remember is to be respectful to the Giant."

"Do tell us about this Giant," said my mother. "I know it is the mountain, of course."

"Well, this island is one of a volcanic group, as you know. It must have come into being millions of years ago when the earth's crust was being formed and it was all internal eruptions. Thus the old Giant was thrown up. He's the god of the island. You can understand it. They think he has power over life and death and he has to be placated. They pay homage to him. Shells, flowers and feathers adorn the mountainside, and when he starts to grumble they get seriously worried. He's an old devil, that mountain. Once it really did erupt. It must have been three hundred years ago and it all but destroyed the island. Now he grumbles from time to time and sends out a few pieces of stone and lava ... to warn them."

"We should have chosen another island, I think," said my mother. "I don't like the sound of this Grumbling Giant."

"He's safe enough. Remember he hasn't been what you could call really active for three hundred years. The little grumblings are a safety valve really. He's done his erupting. In another hundred years he'll have settled down entirely."

He introduced us to Cougaba, who had served him well and was willing to do the same for us. He hoped he could persuade us to keep her, for she would find it hard to go from the big house and settle in one of the native huts now. She had been with him for almost the whole of the twenty years he had spent on the island. She had a daughter, Cougabel, who should be allowed to stay with her mother in the house.

"They'll make you good servants," said Luke Carter. "And they'll be a kind of go-between with the natives and yourselves."

My mother declared at once that she would be pleased to have them both, for she had been apprehensive about getting the right servants.

So the first weeks on Vulcan Island passed and by the time Luke Carter was ready to go we were settled in.

My father had already made an impression. He was a very tall man—six feet four in his stockinged feet—and the islanders were a small people. That gave him an immediate advantage. Then there was his personality. He was a man born to dominate and this he proceeded to do. Luke Carter had explained to some of the islanders that my father was a great doctor and he had come to help make the people well. He had special medicines and he believed he could bring great good to the island.

The islanders were disappointed. They had Wandalo. What did they want with another medicine man? What they really wanted was someone to continue marketing the products of the coconut and bring back to the island the prosperity which had once been theirs.

It did seem a pity not to exploit the natural resources. Vulcan Island was the biggest of the group and was all that one imagines a South Sea island should be—hot sun, heavy rains, waving palms and sandy beaches. My father had said that he wanted to call the place Palm Tree Island when he first saw it, but it had already been named Vulcan, which was equally apt really because of the presence of the Giant.

It was a beautiful island—some fifty miles by ten—lush, luxuriant, dominated by the great mountain. It was grand, that mountain, the more so because it was awe-inspiring and, strangely enough, when one stood close to it—and it was not possible to be far away from it on that island—it seemed to possess those rare qualities with which the natives endowed it. The valleys were fertile, but if one glanced up one could see the ravages on the top slopes where the Giant's anger had boiled over and scarred the earth. But in the valleys trees and shrubs grew close together. Casuarina, candlenut and kauri pine flourished in abundance beside breadfruit, sago plant, oranges, pineapple, sweet banana and of course the inevitable coconut palm.

The Giant had to be watched. He could grow angry, Cougaba told me, for she quickly attached herself to me and became a sort of nurse and maid. I grew fond of her and my mother was pleased by this and encouraged it. Cougaba was grateful because not only did she stay in the house but her daughter did also. She was clearly fond of her daughter, who must have been about my age, but it was difficult to tell with the natives. She was a considerably lighter shade than her mother and her smooth light brown skin was very attractive. She had dancing brown eyes and liked to adorn herself with shells and beads, many of them dyed red with dragon's blood. Cougabel was a very important little girl. A certain respect was shown to her. It was because of her birth. She herself told me that she was a child of the mask. What that meant I learned later.

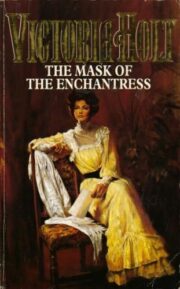

"The Mask of the Enchantress" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Mask of the Enchantress". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Mask of the Enchantress" друзьям в соцсетях.