"It's too late now."

He leaned towards me. "It's never too late."

"But Jessamy is your wife ... soon to bear your child."

"You are here," he said, "and I am here... ."

"I think I should leave the castle."

"You must not do that. If you did I should follow you, so you would achieve nothing by going. Anabel, you and I are of a kind; we were meant for each other. It was there between us right from the first. You know that as well as I do. Only rarely in life does one meet the right person at the right time."

"But we have met at the wrong time," I reminded him. "Too late... ."

"We're not going to let ourselves be hemmed in by conventions. We'll push aside these man-made barriers. You're here and I'm here. That's enough."

"No. No," I persisted. "Jessamy is my dear cousin. She is good and quite incapable of disloyalty and unkindness. We must not betray her."

"I tell you we are going to be together, Anabel," he said firmly. "For the rest of our lives, I swear it. Do you think I'm going to let you go? You're not the sort to let conventions ruin your life."

"No, perhaps not. But there is Jessamy. If it were anyone else ..."

"Let's tether our horses here and talk. I want to hold you ... make you understand... ."

"No," I said quickly. "No." And I turned my horse and galloped away.

But it was inevitable. One afternoon he came to my room. Jessamy was sitting in the garden. It was a lovely September day and we were enjoying the sunshine of an Indian summer.

He shut the door and stood there watching me. I had taken off my dress and had been about to change and join Jessamy in the garden.

He took me in his arms and kissed me. He went on kissing me and I was as eager for him as he was for me.

But Jessamy was down there, innocent and unsuspecting, and I clung to the loyalty and love I felt for her.

"No, no," I protested. "Not here."

It was an admission. He held me at arm's length and looked at me.

"You know, Anabel, my love," he said, "that we belong together. Nothing on earth is going to keep us apart."

I did know it.

He went on: "Soon then... ."

And he was smiling.

I don't want to make excuses. There is no excuse. We became lovers. It was wicked of us, but then neither of us is a saint. We could not help it. Our emotions were too strong for us. It is rarely, I am sure, that two people love as we did ... immediately and simultaneously. I am sure to love like that is the happiest state in the world ... if one is free to do so. We tried to forget that we were betraying Jessamy, but of course I could not completely. It was the bitterness in my ecstasy. Perhaps there were times when we were together in closest intimacy when I did forget; but it could not be for long and I found it hard to escape from the memory of Jessamy. She was always in my mind except for those rare moments—and I despised myself for deceiving her because when I looked back I realized that I had known something like this would happen if I came to the castle. I should have been noble and unselfish; I should have taken some post with a disagreeable old woman and pandered to her wishes, taken her nasty little dog for walks, or tried to grapple with the education of little horrors in an alien nursery. I shivered at the thought, and yet, wretched as I should have been, I could have held up my head.

Jessamy had a difficult pregnancy. The doctor said she must keep to her bed, which she did. She was uncomplaining, eagerly looking forward to the day when her child would be born. She was very thoughtful towards me. "You must not stay in all day, Anabel," she said. "Take one of the horses and exercise it."

Dear Jessamy and despicable Anabel! I would take one of the horses and ride to the house in the town, and there Joel and I would be together.

He did not suffer so greatly from remorse as I did. He was a Mateland, and Matelands, I imagined, had never denied themselves the gratification of their senses. That there had been many women before me I was fully aware. Oddly enough I regarded this as a challenge. I was going to keep him devoted to me. I was determined on that. Indeed I was a mixture of contrasts at that time. I was exultant, ecstatic and yet filled with a sense of self-loathing and shame. But one thing I did know and that was that I had to behave as I did. It was as though there was some powerful force driving us together. I think he felt it too. He said there had never been anything like it in his life before, and although this is the sort of thing people say lightly in such circumstances, I believed him.

Understand, Suewellyn, that had this not been a mighty and overpowering emotion in me, a certainty that this was the only man I could ever love, I should not have entered into this relationship. I am not a good woman, but I am not a light one.

So while Jessamy was awaiting the birth of her child, I was making ardent love with her husband. We were completely absorbed in each other and it was only when we were alone in that house that we could allow ourselves to act naturally. In the castle we had to cloak our feelings, and we knew we were involved in a highly dangerous situation. It was not only Jessamy we had to deceive, I was constantly aware of David's watching eyes. He was amused by my rejection of him and at the same time his desires were strengthened by it.

If she knew, Emerald paid no attention to this. I dare say she was accustomed to his philanderings. I often caught Elizabeth Larkham watching me closely. She was Emerald's friend and clearly did not approve of David's interest in me.

As for the old man, he would have been highly amused by the situation if he knew of it, I was sure.

It was a strange household. When I was in the castle I was most at peace with young Esmond. We had become good friends. I used to read to him, and we would sit with Jessamy while she worked at some baby garment and I read aloud. It was a comfort to me to have the boy there; I was very uneasy when I was alone with Jessamy.

I believe that the only person who knew what was happening between me and Joel was Dorothy. She was imperturbable and I could not tell what she thought. It occurred to me that women might have come to the house before. I asked Joel about this and he admitted that it had happened once or twice. He assured me vehemently that that had all been very different. There had never been anything like this, and I believed him.

Elizabeth Larkham's son Garth came to the castle for the summer holidays. He was a noisy boy who behaved as though the castle were his. He was several years older than Esmond and took the lead in their games. I wondered whether Esmond welcomed him. He did not say he did not. He was too polite for that. His mother said it was good for him to have someone near his own age to be with and perhaps it was. There was another boy who came for a short visit. He was a cousin of some sort, named Malcolm Mateland. His grandfather was Egmont's brother.

When I look back now everything that happened seems inevitable. Jessamy's baby was born in November and by that time I had discovered that I was going to have a child.

It was a devastating discovery, although I should have been prepared for it. For several days I kept the information to myself.

Jessamy's baby was a girl. She was called Susannah. It is a custom in our family to give the girls two names by which they are called. Amy Jane for instance. My mother was Susan Ellen. When it came to Jessamy and myself, our names were two strung together. Jessica Amy and Ann Bella. So naturally Jessamy thought of Susan Anna for Susannah.

So wrapped up in her baby was she that Jessamy did not notice my preoccupation.

I discussed my predicament with Joel. He was delighted at the prospect of our having a child and waved aside all the difficulties. I was beginning to understand Joel very well. He was a forceful man, as all the Matelands were. When he was presented with a difficult situation, he always began by assuming that a solution could be found.

"Why, sweetheart," he said, "it's happened millions of times before. We'll find a way."

"I shall have to go away," I said. "I'll find some excuse to leave the castle."

"To go away briefly ... yes. But you're coming back."

"And the child?"

"We'll arrange something."

It took us some time to work out a plan of action. We then arranged that I should tell them at the castle that a distant relative of my father who lived in Scotland was anxious to see me. I had heard my father talk of these people but apparently there had been some quarrel in the family, and now that they had heard my father was dead they wanted to see me.

I told Jessamy that I thought I ought to go.

Jessamy hated quarrels in families and she said why didn't I go for a week or two?

I left it at that. I would go for a week or so ostensibly and then I would find some reason for lengthening my stay.

I was now three months' pregnant. Janet was in the secret. It was impossible to keep it from her. She had been horrified at first, but that snobbery in her arose in my favor. At least the father of my child was the bearer of a great name and his home was a castle. That made the sin more venial in her eyes. She would come with me.

We did not go to Scotland as we had said we would but to a little mountain village near the Pennines and there we lived while we awaited the arrival of the baby. During that time Joel came twice to see me and stayed a few days each time. They were halcyon days. We were together in the mountains and we played a game of make-believe that we were married and that I was not hiding away so that our child could be born in secret.

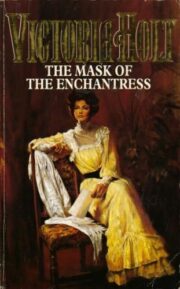

"The Mask of the Enchantress" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Mask of the Enchantress". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Mask of the Enchantress" друзьям в соцсетях.