Jessamy was very unhappy. However, I was the one who told the story, keeping to the truth as far as I could, not telling them how deeply we had penetrated into the woods and eliminating the woman and her fortunetelling.

There was great consternation—more, I realized, because we had been molested, as Aunt Amy Jane put it, than because of the loss of the chain. They sent men into the woods, but the caravan had gone, though there were the wheel marks and the remains of the fire to show where they had been.

Aunt Amy Jane, who managed most things in the village as she did at Seton Manor, had "Trespassers Will Be Prosecuted" put up on signboards all over the woods, and from then on gypsies were not allowed to camp there. I felt overawed to contemplate that this had been brought about by my waywardness, but I consoled myself with the thought that I had not made a thief of the gypsy; he had been that already, so I did not feel there was anything much to worry about.

It was poor innocent Jessamy who worried. She blushed every time gypsies or fortunetelling were mentioned. We had acted a lie, she said, and the recording angel would make a note of it. It would have to be answered for when we got to heaven.

"That's a long time yet," I comforted her. "And if God is what I think He is He won't like that sneaking little recorder very much. It's not nice spying on people and writing down what they do in a little book."

Jessamy was always expecting the heavens to open and God to inflict something terrible upon me. I used to reassure her that He had had plenty of opportunities and He hadn't done anything so far, so it must mean that He thought I was not so very wicked.

Jessamy was unsure. Her life was fraught with fears and indecisions. Poor Jessamy, who had so much and never seemed to take advantage of it.

I was always very interested in Amelia Lang and William Planter. They had been a part of the vicarage household for as long as I could remember, and they had always been the same through the years. Then I discovered that there was, as Janet put it, "something between them." No sooner had I heard this than I was consumed with curiosity to discover what. I used to discuss it with Jessamy and make up all sorts of wild stories about them. William's name delighted me. It was William Planter, which, I said to Jessamy, was a lovely name for a gardener. Now did he become a gardener because his name was Planter or was it just a joke of God's ... or whoever had given him the name in the first place? For William came from a long line of Planters and they had all been noted for their skill in gardening.

I would roll about with delight and get Jessamy doing the same, forgetting all the rules about deportment, choosing names for people like William Planter's. The cook, I said, should be Mrs. Bakewell instead of Mrs. Wells. Thomas, the butler, should possess the obvious for his name. No one seemed to know what his real one was. He was always called Thomas. The footman should be Jack Foot. The coachman George Horsemare. As for Jessamy, she should be Jessamy Good.

It all seemed hilariously funny to me.

I remained very interested in this "something" between William and Amelia. On one rare occasion I induced Amelia to talk of it. Yes, there was an understanding between them, but William had never spoken and, until he did, things must remain as they were.

I could not understand what was meant, for I had heard William speak many times. He wasn't dumb, I pointed out. "He hasn't spoken," insisted Amelia, and that was all she would say.

I was instrumental in getting him to "speak." I managed to get them together one afternoon. I had lured Amelia into the garden to get some roses when I knew William was working on the rose beds.

So, having them together, I said: "William, you will not speak. You must do so right away. Poor Amelia can do nothing until you speak."

They just looked at each other and Amelia went bright pink, and so did William.

Then he said, "Will you then, Amelia?"

And Amelia replied: "Yes, William."

I watched them with satisfaction although they did not seem to be aware of me. But William had "spoken" and now they were engaged.

The engagement went on for several years but it was known that William and Amelia were bespoken from that day, and when Janet told me that meant no one else could have them, I remarked that I did not think anyone else wanted them.

I told her how I had made William "speak."

"Miss Interference!" she said; but I knew she was laughing.

There were always reasons why Amelia and William could not get married. William lived in a small place in the vicarage grounds. It was little more than a hut, and there was not room for two there. The marriage would have to be put off until they could find a place to live.

Amelia chafed under the delay but she was happy that William had spoken. I often reminded her that it was due to my prodding.

Several years passed and then one autumn day William had a fall. He had mounted a ladder to gather apples from the topmost branches when he missed his footing. He broke his leg and it was never right again after that. He limped about the place and developed rheumatism in the afflicted limb and my father spoke to Sir Timothy about him.

Sir Timothy was a kindly man who took a pride in looking after his work people, and of course ours—through Aunt Amy Jane of course—were under his jurisdiction.

It soon became clear that something must be done for William Planter. Sir Timothy, who seemed to have possessions all over the country, owned a cottage on Cherrington green. It was called Crabtree Cottage because of the crabapple tree in front of it.

William was past his best work. He should have an annuity and marry Amelia, whom he had kept hanging about far too long, and they should take up residence in Crabtree Cottage, which should be theirs for their lifetimes.

So William and Amelia married and departed in certain splendor for Cherrington and Crabtree Cottage.

Amelia sent us a card every Christmas and both she and William seemed to have settled into matrimony as comfortably as they did in Crabtree Cottage.

We had a jobbing gardener who also worked at Seton Manor and one of the widows in the village came in to help about the house in Amelia's place.

We were growing up. Jessamy was a few months older than I, but I always thought of myself as the elder.

We were seventeen and there was talk of "coming out." That would not be until we were eighteen and the object would be to find us suitable husbands. Before this great event there were what I called skirmishing parties and it was one of these which did not seem overly significant at the time but which, looking back, I think may have changed the whole course of our lives.

Aunt Amy Jane was inviting some people for a house party. There was to be what she called "a little dance." No, not a ball, just a pleasant evening, a sort of rehearsal, I gathered, for the great campaign which would begin when Jessamy was eighteen.

I was to have one of Jessamy's castoff dresses, made over. My father protested and said I was to go into the town and buy some material and get the village seamstress to make it up for me. Now I knew that any material we could get and any work industrious Sally Summers could put into it would not compare with a made-over garment from Jessamy's wardrobe, for Jessamy's clothes came from London or Bath and they were not only of the latest fashion, which all Sally Summers' neat stitching could not match, but they were of such delicate and expensive materials as we could not hope to acquire.

So I persuaded my father that I was quite happy in Jessamy's castoffs, and when Janet had done with them, no one would notice that they had been altered for me.

It was a beautiful dress—with rather a tight bodice nipped in at the waist and the skirt cascading out into hundreds of frills. It had become too tight for Jessamy and it was ideal for the transformation.

Jessamy was dark-haired and a little sallow; she took after her father and had inherited his nose, which was rather large. She had a sweet expression, though, and lovely dark doelike eyes. I thought that if she could only be a little more animated she would be quite attractive. The dress was pink and it had not matched her complexion. I was fair-haired with light brown eyes and very long gold-tipped lashes; my brows were very firmly defined and of a darker shade than my hair, which made them stand out. My skin was very fair and I had a slightly retrousse nose and a wide mouth. That I was attractive I knew, because people always looked first at me and then looked again. I was by no means beautiful, but I had those high spirits which were irrepressible, for there was little I could do to restrain them. I was always finding something in life so excruciatingly funny that I had to share the joke with someone. To some people—people like Aunt Amy Jane and Amelia—this in me was a decided fault; they shook their heads over it and did everything they could to repress it, but to some people it was amusing and attractive. I knew by the way they smiled when they looked at me.

Well, there we were at this little dance which was to prove so fatal to my future.

The carriage was sent over for me, which was considerate of my aunt, for it would have been awkward to walk from the vicarage to the great house in all my finery.

I arrived before the other guests and went to Jessamy's room. She was in a blue silk dress, all frills and flounces. My heart sank, for it was the wrong color for Jessamy; frills did not really suit her. She looked best in her gray riding habit with its severely tailored coat and the topper with the gray silk band round it.

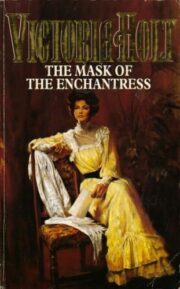

"The Mask of the Enchantress" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Mask of the Enchantress". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Mask of the Enchantress" друзьям в соцсетях.