The fact was that Jessamy was decidedly what kind people call "homely" and those uncomfortable people like Janet, who could never tell a lie however much it might save someone's feelings being hurt, called downright plain.

"Never mind," Janet used to say. "Her father will buy a nice husband for her. You, Miss Anabel, will have to find your own."

Janet pursed her lips when she said this as though she was certain that my hopes of finding one were very frail. Dear Janet, she was the best soul in the world but she was obsessed by her own unshakable veracity from which she would never diverge.

"It's a good thing you're not brought up before the Inquisition, Janet," I said to her once. "You'd still stick out for the silliest little truth in face of the stake."

"Now what are you talking about, Miss Anabel?" she replied. "I never knew anyone who took such flights of fancy. And, mark my words, you'll come a cropper one of these days."

She had seen that prophecy come true; but that was later.

So there I was in my vicarage home with my absent-minded father, down-to-earth honest Janet and Amelia, who was every bit as virtuous as Janet and even more aware of it.

Some people might wonder how I could enjoy life thoroughly but I did. There was so much to do. There was interest all around me. I helped my father quite a bit. I even wrote a sermon for him once and he was halfway through it before he realized it was not the kind of sermon his parishioners wanted to hear. It was all about what constituted a good person and I had unwittingly illustrated my meaning by describing some of the failings of the people who were sitting in the pews listening. Fortunately Father changed to one he kept in a drawer about God's gifts to the land, which was really one for the harvest festival, but as he changed over before my revolutionary words had aroused the congregation from its usual slumber, no one noticed.

I was not allowed to write sermons after that. It was a pity. I should have liked to.

I remember Sundays well. The Seton family were always there in the family pew right in the front under the lectern. They were the big family who lived in the manor and it was to them my father owed his living. They were related to us. Lady Seton was my aunt, for she and my mother had been sisters. Amy Jane had married "well" when she took Sir Timothy Seton, for he was a rich man owning a great deal of land and, I believe, had many possessions as well. It was a very satisfactory match apart from one thing. They had no son to carry on the illustrious Seton name and their hopes rested on their only daughter, Jessamy. Jessamy was constantly indulged, but oddly enough that did not spoil her. She was a rather timid child and I always got the better of her when we were alone. Of course when we were not and there were adults present, they always saw fair play, which meant putting Jessamy in the ascendant.

When we were young and before Jessamy had a governess, she came to the vicarage for lessons because then my father had a curate who used to teach us.

Let me start at the beginning though. There were two sisters-Amy Jane and Susan Ellen. They were the daughters of a parson and when they grew up the younger of the two, Susan Ellen, fell in love with the curate who came to assist her father. He was poor and not in a position to marry but Susan Ellen had never been one to consider the practical side of life. Acting against the advice of her father, the entire village community and her forceful sister, she eloped with the curate. They were very poor because he had no living and they opened a little school and taught in it for a while. Meanwhile Amy Jane, the wise virgin, had made the acquaintance of the wealthy Sir Timothy Seton. He was a widower with no children and he desperately wanted them. Amy Jane was a good-looking, very capable young lady. Why should they not marry? He needed a mistress for his house and children for his nurseries. Amy Jane seemed well equipped to provide them both.

Amy Jane believed she was a suitable wife for him and, what was more important, that he would be the right husband for her. Riches, standing, security—they were three very desirable goals in Amy Jane's eyes. And after the disastrous marriage of her sister there must be someone to reinstate the family fortunes.

So Amy Jane married and in her forceful way set about performing the tasks she had undertaken. In a short while Sir Timothy's household was managed with the utmost skill, to his delight and to slightly less of that of the domestics, for those whom Amy Jane considered not worth their salt were dismissed, and the rest, realizing their fate lay in their ability to please Amy Jane, proceeded to do just that.

It was not long before a living was found for the curate and his reckless bride; and they were to live right under the shadow of Seton Manor.

Amy Jane then set about the next project, which was to fill the nurseries at Seton Manor.

In this she was less successful. She had one miscarriage, which she believed to be an oversight on the part of the Almighty as she had prayed, and set the whole village praying, for a son. But she was almost immediately pregnant and this time that pregnancy was brought to a conclusion and, although it might not be entirely satisfactory, it was at least a start.

Sir Timothy was delighted with the puling infant who, Nurse Abbott declared, had needed an extra smart slap on the posterior to start its breathing. "The next will be a boy," stated Amy Jane, in a voice before which Heaven itself would have quailed. Opposition came from the doctor; Amy Jane would risk her life by trying again. Let her rest content with her girl. The child was responding to treatment and was going to survive. "Don't risk it again," said the doctor. "I could not answer for the consequences." And as neither Amy Jane nor Sir Timothy wished to face such a disaster, there were no more children; and Jessamy, after clinging to life somewhat precariously for a few weeks, suddenly began to clamor for food and to kick and cry the same as other children.

A few months after the birth of Jessamy, life and death came to the vicarage hand in hand. Amy Jane was shocked. My mother had always been a great disappointment to her. Not only had she made a disastrous marriage, but just when her capable sister was putting her on her feet in a very pleasant living which Sir Timothy had secured with some effort, for there were others who were in fact more deserving than my father, she had given birth to a child and died doing it. A small baby in a vicarage with a man who was more than usually helpless was inconvenient to say the least, but a woman of Amy Jane's caliber was not to be deterred. She found Janet and installed her. Henceforth I was cared for, and Amy Jane, as my mother's closest relative, would of course keep an eye on me.

This she undoubtedly did and her own precious Jessamy was a part of my childhood and girlhood. It was Jessamy's clothes which came to the vicarage and were made over for me. I was slightly taller, which would have made them short, but she was broader-shouldered and took them up more. Janet said it was child's play to take them in a bit and there was better stuff in them than any that would find their way into this house from the shops.

"You look a sight better in them than Miss Jessamy," she would say and, coming from can't-tell-a-lie Janet, that was gratifying.

So I was accustomed to wearing castoff clothes. I can remember very few that did not come via Jessamy. Spending such a lot of time with her, wearing her old garments, did make me become a part of her life.

There was one time when Aunt Amy Jane thought it was fashionable to send girls to school, and there was talk of our going. I was excited at the idea. Jessamy was terrified. Then Dr. Cecil, he who had suggested that there should be no other Seton child in the nursery but Jessamy, decided that she was not strong enough for a boarding school. "Her chest," was all he said. So no school it was, and as Jessamy's chest was too weak to let her go, mine, strong as it might be—and it had never given me or Dr. Cecil any indication that it was not—could not take me there. Fees would have to be paid by Sir Timothy, and it was not to be thought of that I should be sent and paid for while his daughter remained at home.

When there was entertaining at Seton Manor, Aunt Amy Jane always did her duty and invited me. When she came to the vicarage she rode over in the carriage with a foot warmer in the winter and a parasol in the summer. On winter days she would pick up her beautiful sable muff and alight from the carriage while the Seton coachman held open the door with the utmost display of deference and she would march into the house. In the summer she would hand her parasol to the coachman, who would solemnly open it and hold it out in one hand while he helped her to alight with the other. I used to watch this ritual from one of the upstairs windows with a mixture of hilarity and awe.

My father would receive her in a somewhat embarrassed way. He would be frantically feeling for his spectacles, which he had pushed up on his head. They always slipped too far back and he would think he had put them down somewhere—which he did now and then.

The purpose of her visit was certain to be me, because I was her Duty. She had no reason to bother herself about a man who owed his living to her benevolence—or Sir Timothy's, but all blessings which fell on our household came through her, of course. I would be sent for and studied intently. Janet said that Lady Seton did not really like me because I looked healthier than Miss Jessamy and reminded her of her daughter's weak chest and other ailments. I was not sure whether Janet was right but I did feel that Aunt Amy Jane was not really fond of me. Her concern for my welfare was out of duty instead of affection, and I have never relished being the object of duty. I doubt anyone ever does.

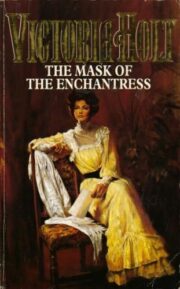

"The Mask of the Enchantress" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Mask of the Enchantress". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Mask of the Enchantress" друзьям в соцсетях.