I waited for her to go on but she did not, and I was too busy thinking how wonderfully it had all turned out for me to ask. I had gained not ordinary parents but these two. It was indeed a miracle after having none.

The journey continued. It was always hot and I had to think hard to remember the east wind blowing across the green and how in winter I had to break the thin layer of ice to get the water to wash from the ewer in my bedroom.

That was all far away and becoming more and more hazy in my mind as my new life imposed itself on the old.

In time we came to Sydney, a town of beauty and excitement. As we passed through the Heads, I watched with my parents on either side of me and my father told me how many years ago prisoners had been brought here to get them out of England. This coast was rather like the one we had in England ... or Wales rather, and it had therefore been named New South Wales.

"The finest harbor in the world," said my father. "That's what they called it then and it still is."

It was too much for a child of my age to absorb. A new family; a new country; a new life. But because I was so young, I just lived from day to day and each morning when I awoke it was with a sense of excitement and happiness.

I learned a little about Sydney. We were there for three months. We found a house near the harbor, which we rented for a short period, and there we lived very quietly. A vague uneasiness had crept into the household which had not been there when we were on the ship. Anabel was more frequently affected by it than my father. It was almost as though she were afraid of too much happiness.

I felt a twinge of fear too.

I said to her once: "Anabel, if you are too happy can something take it all away from you?"

She was very perceptive. She understood at once that some of her anxiety had come through to me.

"Nothing is going to take us away from each other," she said at last.

My father went away for what seemed like a long time. Each day we would watch for the return of the ship which would bring him. Anabel grew sad, I knew, though she tried not to let me see it. We went on living as we had when the three of us were together; but I could see she was different. She was always looking across the sea.

Then one day he came back.

He was very pleased. He held her tightly in his arms and then he picked me up, still holding her with one arm.

He said: "We're going away. I've found the place. You'll like it. We can settle there ... miles out in the ocean. You'll feel safe there, Anabel."

"Safe," she repeated. "Yes ... that's what I want ... to feel safe. Where is it?"

"Where is a map?"

We pored over the map. Australia was like a circle of dough which had been kneaded slightly out of shape. New Zealand was two dogs fighting each other. And there right out in the blue ocean were several little black dots.

My father was pointing to one of these.

"Ideal," he was saying. "Isolated ... except for a group of the same islands. This is the largest. Little goes on there. The people are inclined to be friendly ... easygoing ... just what you would expect. There has been some cultivation of the coconut, but little now. There are palms all over the place. I called it Palmtree Island but it is already named Vulcan. They are in need of a doctor there. There is none on the island ... no school ... nothing. ... It is the place where one can lose oneself ... a place to develop ... a place to offer something to. Oh, Anabel, I like it. You will too."

"And Suewellyn?"

"I've thought of Suewellyn. You can teach her for a few years and then she can go to school in Sydney. We're not all that far. A ship calls once now and then to collect the copra. It's the place, Anabel. I knew it as soon as I saw it."

"What shall we need?" she asked.

"Lots and lots of things. We have a month or so. The ship calls every two months. I want us to be on the next one that goes. In the meantime we are going to be busy."

We were busy. We bought all kinds of things—furniture, clothes, stores of all sorts.

"My father must be a very rich man," I said. "Aunt Amelia said she always looked twice before she spent a farthing." Take care of the pence and the pounds will take care of themselves was one of her favorite sayings. Waste not, want not was another. Every crust of bread had to be made into a bread and butter pudding, and I was often in trouble for feeding the birds in winter.

My father talked a great deal about the island. Palms grew in abundance, but there were other trees as well as breadfruit, bananas, oranges and lemons.

There was a house there which had been built for the man who had made a thriving industry out of the cultivation of coconuts. My father had taken over the house at a bargain price.

All our baggage was put on board the ship and we set sail. I don't remember what time of year it was. One forgot because there were no seasons as I had known them. It was always summer.

What I shall never forget is my first glimpse of Vulcan Island. I immediately noticed the enormous peak which seemed to rise up out of the sea and was visible long before we reached the island.

"It has a strange name, that island," said my father. "It is called something which when translated means the Grumbling Giant."

We were standing on deck, the three of us hand in hand, watching for the first glimpse of our new home. And there it was —a great peak rising out of the sea.

"Why does it grumble?" I asked eagerly.

"It's always grumbled. Sometimes when it gets really angry it sends out a few stones and boulders. They are boiling hot."

"Is it really a giant?" I asked. "I have never seen one."

"Well, you are going to make the acquaintance of the Grumbling Giant, but it's not a real giant," answered my father. "I'm afraid it is only a mountain. It dominates the island. The native name is Grumbling Giant Island but some travelers came by long ago and called it Vulcan. So on the maps it has become that."

We remained there looking and in due course the land seemed to form itself about the great mountain and there were yellow sands and waving palms everywhere.

"It's like a paradise," said Anabel.

"We are going to make it that," answered my father.

We could not go right in to the island and had to anchor quite a mile out. There was a tremendous bustle of activity on the shore. Brown-skinned people paddled out in light slim craft which I afterwards learned were called canoes. They were shouting and gesticulating and mostly laughing.

Our possessions were loaded into some of the ship's lifeboats and they and the canoes brought them ashore.

When the goods had all gone, we were taken.

Then the little boats were drawn up and the big ship set sail, leaving us in our new home on Vulcan Island.

There was so much to do, so much to see. I could not entirely believe it was all happening. It seemed like something out of an adventure story.

Anabel was aware of my bewilderment.

She said: "One day you will understand."

"Tell me now," I begged.

She shook her head. "You would not understand now. I want to leave it until you are older. I am going to start writing it down now so that you can read it when you are older and understand. Oh, Suewellyn, I do want you to understand. I don't want you ever to blame us. We love you. You are our very own child and, because of the way it happened, it only makes us love you more."

She could see that I was very puzzled. She kissed me and, holding me close to her, went on: "I'm going to tell you all about it. Why you're here ... why we're all here ... how it came about. There was nothing else we could do. You must not blame your father ... nor me. We are not like Amelia and William." She gave a little laugh. "They live ... safely. That's the word I was looking for. We don't. It's not in our nature to. I have a feeling that you might be as we are." Then she laughed again. "Well, that's the way we're made. And yet ... Suewellyn, we're going to settle here ... we're going to like it. We're going to remember all the time if we feel homesick ... that we're together and this is the only way we can stay together."

I put my arms round her neck. I was overwhelmed by my love for her.

"We're never, never going to leave each other, are we?" I asked fearfully.

"Never," she said vehemently. "Only death can part us. But who wants to talk about death? Here is life. Don't you feel it, Suewellyn? It's teeming with life here. You only have to lift a stone and there it is... ." She grimaced. "Mind you, I could do without the ants and termites and suchlike... . But there's life here ... and it's our life ... the three of us together. Be patient, my dearest child. Be happy. Let's live for each day as it comes along. Can you do that?"

I nodded vigorously, and we walked together through the palm trees to where the warm tropical water rippled onto the sandy beach.

Anabel's Story

Jessamy had played a big part in my life. She had always been there. She was rich, petted and the only child of doting parents. I never envied her her pretty clothes and her jewelry. I am not, I believe, envious by nature. It is one of my virtues, and as I have few others it is advisable to record it. In any case I always believed I had so much more than she did.

It was true I did not live in a mansion surrounded by servants. I did not have several ponies which I could ride as the fancy took me. I lived in a rambling vicarage with my widowed father —my mother had died giving birth to me—and we had two servants only, Janet and Amelia. Neither of them exactly doted on me, but I think Janet was fond of me in her way, though she would never admit it. They were both quick and eager to tell me of my faults. But I was happier, I think, yes, a great deal happier than Jessamy.

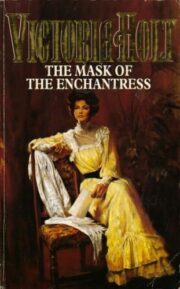

"The Mask of the Enchantress" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Mask of the Enchantress". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Mask of the Enchantress" друзьям в соцсетях.