'My head feels like a gambeson, he said, as Richard cheerfully thrust a cup of hot wine beneath his nose. 'So stuffed with wool that whatever strikes it is just absorbed without result.

Richard grinned. 'At least we'll reach Bristol tomorrow, he said cheerfully.

Oliver took a sip of the steaming wine. It was sour but he didn't care as long as it revived him. 'Then what? He glanced at Henry who was prowling confidently around the room talking to his commanders, his short, stubby hands gesturing eloquently as he spoke. Even now, at the end of a long, harrowing day, he was still on his feet with a bounce in his stride. In a moment Oliver knew with awful certainty that the Prince was going to ask him a preposterous question about their supplies and expect him to have the answer.

Richard shrugged. 'Then we eat an enormous meal safe behind huge walls where Stephen cannot reach us, and in the morning we start planning again.

Oliver groaned. Actually the planning did not bother him too much. He was quick and efficient at working out logistics, and supplies were always easier to come by in the summer months. What he disliked were the fits and starts of campaigning, the furtive hiding, sleeping in full mail, a horse beneath him. Although still very young, Henry was a competent commander, but Stephen was competent too and also battle-wise. To best him, Henry needed the luck of the devil, who was said to be his ancestor, and thus far it had not been forthcoming.

'Very soon I will have spent half my life on the battlefield. My bones, including the broken ones, are too weary to do anything now but lie down.

Richard tilted his head on one side. 'Catrin and Rosamund are in Bristol, he said. 'We'll reach them tomorrow too, and Geoff FitzMar.

Oliver nodded to humour the young man and wondered if Richard's resilience was the result of being a full fifteen years younger or whether it was a derangement of the royal bloodline. While Oliver was indeed looking forward to seeing Catrin and Rosamund, he was too bone-weary to make the effort of conversation. The last decent night's sleep he remembered was in Carlisle before setting out for Lancaster, and even that had been marred by Henry's propensity for rising three hours before the lark. He had never known anyone need so little rest.

Giving up on Oliver's tepid response, Richard drifted away to join Thomas FitzRainald who was spreading his saddle-roll near the hearth to air out the damp. With a quick glance in Henry's direction, Oliver took his own saddle-roll outside, deciding to find a quiet, sheltered spot in the bailey where he could sleep in peace. The Prince needed to know nothing from him at the moment. Let him bedevil some other poor individual for his intellectual stimulation.

It was a quiet night, thick with stars. Sentries paced the wall-walks, their boots scraping softly on the wooden planks. Sheep bleated to each other in the fields beyond the walls and danger seemed so far away that it had no meaning. Oliver found an animal shelter supported on two strong ash poles. It smelt faintly of goat, but there was no sign of an occupant and the straw on the floor was clean and dry. He spread his cloak, lay down upon it and wrapped it over like a blanket. Within moments he was sound asleep.

It seemed only seconds later, but was more than three hours judging from the position of the stars, when he was woken by the sound of someone crying for admittance at the keep gates. There was urgency in the voice and as Oliver threw off his cloak and sat up, he saw guards hastening by torchlight to raise the bar and admit a rider. As the horse clattered into the bailey, Oliver recognised one of Henry's Welsh scouts.

The man tethered his blowing mount to a ring in the wall and headed towards the darkened keep. Starlight glittered, casting blue light beyond the red of the guards' torches.

'Math? Oliver called.

The Welshman turned, his hand by instinct already on his dagger, then he relaxed. 'Oh, it's you, the pet Saeson, he said in his broad, sing-song accent. 'What are you doing out here?

'Trying to sleep without being disturbed, Oliver said with a shrug. 'I should have known it was a lost cause.

'Aye, well, the entire cause of yon lad will be lost if you don't put spurs to your mounts and ride for Bristol, Math said. 'Eustace has an army not twenty miles away and he's headed straight here. He knows that Henry's inside. Math gazed around at the walls, his mouth turned down at the corners. 'Not fit for a siege, this one. I'd sooner be attacking it from without than hiding within, see.

Oliver followed Math into the keep to raise the alarm and bade farewell to sleep.

The next hour was complete hell as men were roused from their slumber and forced to don armour and weapons which they had but recently removed. The horses were tired. Some just hung their heads and patiently allowed themselves to be saddled — which did not bode well for swiftness on the road. Others, with more spirit, kicked and snapped as the harassed grooms and squires tried to harness them by the poor light of guttering pitch flares.

The Prince was one of the first to leave Dursley, riding on a fresh horse borrowed from the castellan. His capture could not be risked with Eustace and his army so close. Stephen's eldest son was neither generous nor amenable and Henry was his bitter rival.

' Oliver rode out with Henry's rearguard. Hero was seventeen years old and beginning to show his age. He did not have the kick or spark of the younger mounts, nor their stamina any more. Still, he responded gamely to Oliver's urgency and broke into a trot. Only a madman or someone completely desperate would have galloped his mount in the dark, and so Oliver was able to keep pace with the rest of the troop.

There was a prickling between his shoulder blades as he rode, and his sleep-starved imagination fed him a waking dream of being pursued not by Eustace but by Louis de Grosmont. Closer and closer the spectre came, his sword raised and his dark eyes reflecting the glow from the travelling torches like hell-fire. No matter how much Oliver spurred Hero, Grosmont continued to close on them.

'She's mine! Grosmont snarled at Oliver. 'Mine until death!

'You can't have her! Oliver sobbed and drew his sword. The sound shivered the night and brought him awake with a huge surge of breath like a man too long submerged. His sword was in his hand, braced and ready.

'What is it? Beside him, Richard's own sword was half out of the scabbard. 'Have you seen something? The youngster's eye whites gleamed with fear.

'No. Oliver passed his hand across his eyes. 'I was saddle-sleeping, he admitted sheepishly. 'I thought we were being hard-pursued.

Richard glanced over his shoulder into the darkness, his expression intent. Then, with a sigh, he slotted his weapon home. 'Nothing, he said. 'Jesu, you frightened me yelling like that and drawing your blade. Despite himself, he looked over his shoulder again. There was silence except for the thud of their own horses on the baked mud road, and the soft creak and clink of leather and harness. 'Sorry. I'll try and stay awake.

'Be light soon. Richard cast a glance at the sky. There was a milky opacity in the east and the stars no longer burned as brightly. 'Eustace won't dare pursue us as far as Bristol.

Oliver shrugged. 'You never can tell with Eustace. He's half wolf at least.

'Was he in your dream? Richard asked curiously.

Oliver shook his head. 'No, but another wolf was — one in sheep's clothing.

The milkiness in the east took on an opalescent quality. A dawn chorus of birds filled the air from every coppice and field; trees and grass turned from grey to summer-green as the daylight brightened. The men doused their torches and began to speak in less hushed tones as the strengthening light and the rising sun increased their confidence.

It was just after daybreak when Oliver felt the change in Hero's gait. The smooth lope had given way a while back to a shorter stride as the horse grew tired, but now there was a definite lurch. With a soft curse, Oliver dismounted and ran his hand down the stallion's foreleg. There was a hot, tender swelling on the knee, puffy to the touch, and the horse stamped and tossed his head at the pressure of Oliver's hand.

Richard circled his mount and returned to Oliver and Hero, his blue eyes troubled. 'Do you want to ride double with me?

Oliver gazed round. The landmarks were familiar now. Although they still wanted several miles to Bristol and safety, there was another haven closer to hand. 'No, lad, go on with the others. Godard and Edith live close by. I'll rest Hero with them and borrow a horse, if they have one. Tell Catrin for me.

'Are you sure? Richard glanced behind at the powdery dust settling in the troop's wake as if expecting to see an army of vengeful mercenaries bearing down on them at full gallop.

'It's all right. Eustace isn't that close. Go on with you.

With reluctance, Richard rode away to rejoin the rest of the rearguard, by now a furlong in front of him.

The silence of summer birdsong and the hissing of the wind in the grass filled Oliver's ears with its tranquil immensity. He wrapped his hand around the bridle and led a limping Hero through the army's dust until they came to the branch in the road that led to Ashbury.

'By all the saints, Lord Oliver! Godard put down the curry comb he had been using on the old brown cob and strode to greet his former master. A grin broke across his face, parting the luxuriant beard. "Tis right good to see you!

"Tis right good to see you too, Oliver responded, as they clasped hands. 'Hero went lame a mile back and the troop couldn't afford to wait. I need rest and shelter… and a place to hide.

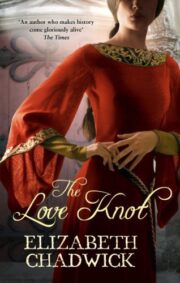

"The Love Knot" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Love Knot". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Love Knot" друзьям в соцсетях.