Only the best of inns would do for such a traveling party, and of course they would expect the finest set of rooms in each establishment.

If the rooms were already reserved, the innkeepers would have to make arrangements to place the other travelers elsewhere. The dowager told Grace that she liked to send someone ahead in cases like these. It was only polite to give the innkeepers a bit of notice so they could find alternate accommodations for their other guests.

Grace thought it would have been more polite not to give the boot to people whose only crime was to reserve a room prior to the dowager, but all she could do was offer the poor secretary a sympathetic smile. The dowager wasn’t going to change her ways, and besides, she’d already launched into her next set of instructions, which pertained to cleanliness, food, and the preferred dimensions of hand towels.

Grace spent her days dashing about the castle, preparing for the voyage and passing along important messages, since the other three inhabitants seemed determined to avoid one another.

The dowager was as surly and rude as ever, but now there was an underlying layer of giddiness that Grace found disconcerting. The dowager was excited about the upcoming journey. It was enough to leave even the most experienced of companions uneasy; the dowager was never excited about anything. Pleased, yes; satisfied, often (although unsatisfied was a far more frequent emotion). But excited? Grace had never witnessed it.

It was odd, because the dowager did not seem to like Mr. Audley very well, and it was clear that she respected him not at all. And as for Mr. Audley-he returned the sentiment in spades. He was much like Thomas in that regard. It seemed to Grace that the two men might have been fast friends had they not met under such strained circumstances.

But while Thomas’s dealings with the dowager were frank and direct, Mr. Audley was much more sly. He was always provoking the dowager when in her company, always ready with a comment so subtle that Grace could only be sure of his meaning when she caught his secret smile.

There was always a secret smile. And it was always for her.

Even now, just thinking about it, she found herself hugging her arms to her body, as if holding it tightly against her heart. When he smiled at her, she felt it-as if it were more than something to be seen. It landed upon her like a kiss, and her body responded in kind-a little flip in her stomach, pink heat on her cheeks. She maintained her composure, because that was what she’d been trained to do, and she even managed her own sort of reply-the tiniest of curves at the corners of her mouth, maybe a change in the way she held her gaze. She knew he saw it, too. He saw everything. He liked to play at being obtuse, but he had the keenest eye for observation she had ever known.

And all through this, the dowager pressed forward, single-minded in her determination to wrest the title from Thomas and give it to Mr. Audley. When the dowager spoke of their upcoming journey, it was never if they found proof, it was when they found it. Already she had begun to plan how best to announce the change to the rest of society.

Grace had noticed that she was not particularly discreet about it, either. What was it the dowager had said just the other day-right in front of Thomas? Something about having to redraw endless contracts to reflect the proper ducal name. She had even turned to him and asked if he thought that anything he’d signed while duke was legally binding.

Grace had thought Thomas a master of restraint for not throttling her on the spot. Indeed, all he said was, “It will hardly be my problem should that come to pass.” And then, with a mocking bow in the dowager’s direction, he left the room.

Grace was not sure why she was so surprised that the dowager did not censor herself in front of Thomas; it wasn’t as if she’d shown a care for anyone else’s feelings before. But surely this qualified as extraordinary circumstances. Surely even Augusta Cavendish could see where it might be hurtful to stand in front of Thomas and talk about how she planned to go about his public humiliation.

And as for Thomas-he was not himself. He was drinking too much, and when he wasn’t closeted in his study, he stalked about the house like a moody lion. Grace tried to avoid him, partly because he was in such poor temper, but mostly because she felt so guilty about everything, so unconscionably disloyal for liking Mr. Audley so well.

Which left him. Mr. Audley. She’d been spending too much time with him. She knew it but could not seem to help herself. And it really wasn’t her fault. The dowager kept sending her on errands that put her in his sphere.

Liverpool or Holyhead-which port made better sense for their departure? Surely Jack (the dowager still refused to call him Mr. Audley, and he would not respond to anything Cavendish) would know.

What might they expect from the weather? Find Jack and ask his opinion.

Could one obtain a decent pot of tea in Ireland? What about once they’d left the environs of Dublin? And then, after Grace had reported back with Yes and for God’s sake (amended to remove the blasphemy), she was sent on her way again to determine if he even knew how to judge a tea’s quality.

It was almost embarrassing to ask him this. It should have been, but by that point they were bursting out laughing just at the sight of each other. It was like that all the time now. He would smile. And then she would smile. And she was reminded just how much better she liked herself when she had reason to smile.

Just now the dowager had ordered her to find him for a full accounting of their proposed route through Ireland, which Grace found odd, since she would have thought the dowager had worked that out by then. But she was not about to complain, not when the task both removed her from the dowager’s presence and placed her in Mr. Audley’s.

” Jack,” she whispered to herself. He was Jack. His name suited him perfectly, dashing and carefree. John was far too staid, and Mr. Audley too formal. She wanted him to be Jack, even though she had not allowed herself to say it aloud to him, not since their kiss.

He had teased her about it-he always teased her about it. He’d prodded and cajoled and told her she must use his given name or he would not respond, but she remained steadfast. Because once she did, she was afraid she could never go back. And she was already so perilously close to losing her heart forever.

It could happen. It would happen if she let it. She had only to let go. She could close her eyes and imagine a future…with him, and children, and so much laughter.

But not here. Not at Belgrave, with him as the duke.

She wanted Sillsby back. Not the house, since that could never be, but the feeling of it. The comfortable warmth, the kitchen garden that her mother had never been too important to attend. She wanted the evenings in the sitting room-the sitting room, she reminded herself, the only one. Nothing that had to be described with a color or a fabric or a location within the building. She wanted to read by the fire with her husband, pointing out bits that amused her, and laughing when he did the same.

That was what she wanted, and when she had the courage to be honest with herself, she knew that she wanted it with him.

But she wasn’t often honest with herself. What was the point? He didn’t know who he was; how could she know what to dream?

She was protecting herself, holding her heart in armor until she had an answer. Because if he was the Duke of Wyndham, then she was a fool.

As fine a house as Belgrave was, Jack much preferred to spend time out of doors, and now that his mount had been transferred to the Wyndham stables (where his horse was certainly wallowing in joy over the endless carrots and warm accommodations), he had taken up the habit of a ride each morning.

Not that this was so very far from his prior routine; Jack usually found himself on horseback by late morning. The difference was that before he’d been going somewhere, or, on occasion, fleeing from somewhere. Now he was out and about for sport, for constitutional exercise. Strange, the life of a gentleman. Physical exertion was achieved through organized behavior, and not, as the rest of society got it, through an honest day’s work.

Or a dishonest one, as the case often was.

He was returning to the house-it was difficult to call it a castle, even though that’s what it was; it always made him want to roll his eyes-on his fourth day at Belgrave, feeling invigorated by the soft bite of the wind over the fields.

As he walked up the steps to the main door, he caught himself peering this way and that, hoping for a glimpse of Grace even though it was highly unlikely she’d be out of doors. He was always hoping for a glimpse of Grace, no matter where he was. Just the sight of her made something tickle and fizz within his chest. Half the time she did not even see him, which he did not mind. He rather enjoyed watching her go about her duties. But if he stared long enough-and he always did; there was never any good reason to place his eyes anywhere else-she always sensed him. Eventually, even if he was at an odd angle, or obscured in shadows, she felt his presence, and she’d turn.

He always tried to play the seducer then, to gaze at her with smoldering intensity, to see if she’d melt in a pool of whimpering desire.

But he never did. Because all he could do, whenever she looked back at him, was smile like a lovesick fool. He would have been disgusted with himself, except that she always smiled in return, which never failed to turn the tickle and fizz into something even more bubbly and carefree.

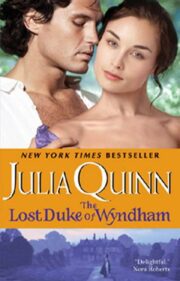

"The Lost Duke of Wyndham" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Lost Duke of Wyndham". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Lost Duke of Wyndham" друзьям в соцсетях.