“You don't know how lucky you are, my dear. Don't waste it with regrets of the places and people you have lost. You have a lifetime to fill, so many good times and good years and great people ahead of you. You must rush to meet it.” But she wasn't rushing lately. She was still barely crawling, and she knew it. But what he said to her touched her deeply.

“Sometimes it's difficult not to look back,” Gabriella mused to him, and in her case, she had a great deal to look back at, and not all of it pretty.

“We all do that at times. The secret is in not looking back too often. Just take the good times with you, and leave the bad times behind you.” But she had so many of them, and the good times had been so sweet and so brief, and there had been so few of them, except for her peaceful years at the convent. But now, even the memory of that was painful, because she had lost it. And yet, she had to admire him. His life was mostly behind him, and he was still looking ahead with enthusiasm and excitement and interest. He liked talking to her, and keeping up with the young, and he hadn't lost his energy or his sense of humor. She found it extremely impressive, and he set a worthy example to the others. The other people in the room were complaining about their health, their ills, the size of their social security benefits, their friends who had died recently, the condition of the sidewalks in New York, and the amount of dog poop they saw there. He cared about none of that. He was far more interested in Gabriella and the life she had ahead of her. He was offering her a road map to happiness and freedom.

She sat with him for a long time that night. He never played bridge with Mrs. Rosenstein and her friends, he said he hated it, but eventually he played dominoes with Gabriella, and she truly enjoyed it. He beat her every time, but she learned a lot from him, and when she went upstairs to her room finally, she had had a delightful evening. They were small pleasures that they shared, but she suddenly felt as though her life was filled with new adventures. She had spent the evening talking to an eighty-year-old man, but he was far more interesting to her than anyone half his age, or half that again. And she was looking forward to speaking with him again, and had even promised him she'd stop on the way to work the next day, and buy a notebook for her writing.

And when he came to Baum's the next day, this time without Mrs. Rosenstein, who had gone to the urologist, he asked Gabriella if she'd done it.

“Well, did you?” he asked portentously, and she didn't know what he meant by the question, as she wrote down his standard order for coffee and apple strudel.

“Did I what?” She'd been busy all afternoon, and she was a little distracted.

“Did you buy the notebook?”

“Oh.” She grinned at him victoriously, amused by his persistence. “Yes, I did.”

“I'm proud of you. Now, when you come home from work tonight, you must start to fill it.”

“I'm too tired when I come home from work at night,” she complained, she was still exhausted from the blood loss she'd suffered in the miscarriage, though she didn't want anyone to know it. The doctor had said it would take months to improve, and she was beginning to believe him. But Professor Thomas was not accepting any excuses.

“Then do it in the morning, before work. I want you to start writing every day. It's good for the heart, the soul, the mind, the health, the body. If you're a writer, Gabriella, it's a life support system you can't live without, and shouldn't. Write daily“ he emphasized, and then pretended to glare at her. “Now go get me my strudel.”

“Yes, sir.” He was like a benevolent grandfather, one she had never had, and had never even known enough to dream of, she'd always been far too busy concentrating on her parents, and what they represented to her. But the presence of Professor Thomas in her life was a real gift, and she thoroughly enjoyed him.

He continued to come to see her every day, and on Mondays when she was off, he began taking her to dinner. He told her about his teaching days, his wife, his life in Washington as a boy, growing up in the 1890s. It was a time she could barely imagine it seemed so long ago, and yet he seemed so aware of what was happening in the present day, and so completely modern. She loved talking to him, and listening even more than talking. And more than anything, they talked about writing. She had written a short story finally, and he was extremely impressed with it, made a few corrections, and explained how she could have developed the plot more effectively, and told her she had real talent. She tried to brush off his compliments, and told him he was just being kind to her, and he got very annoyed, and wagged his famous finger at her. That had always been a sign of danger to his students, but she was anything but frightened of Professor Thomas. She was growing to love him.

“When I say you have talent, young lady, I mean it. They didn't hire me at Harvard to grow bananas. You have work to do, you still need some polishing, but you have an instinctive sense for the right tone, the right pace… it's all a question of timing, of sensing when to say what, and how, and you have that. Don't you understand that? Or are you just a coward? Is that it? Are you afraid to write, Gabriella? Afraid you might be good? Well, you are, so face it, live up to it. It's a gift, and few people have it. Don't waste it!” They both knew she was no coward, and then she smiled sadly at him, remembering the words she had always hated.

“Usually people tell me how strong I am,” she said, sharing one of her secrets with him. It was the first of many. “And then they leave me.”

He nodded wisely and waited for her to say more, but she didn't. “Perhaps they're the cowards then. Weak people usually congratulate others for their strength so they don't have to be strong, or they use it as an excuse to hurt you… it's a way of saying, You can take it, you're strong.’ A great deal is expected of strong people in this world, Gabbie. It's a heavy burden,” and he could see it had been. “You are strong though. And one day you'll find someone as strong as you are. You deserve that.”

“I think I already have.” She smiled at him, and patted the gnarled hand with the wagging finger which was at rest now.

“You're just lucky I'm not fifty or sixty years younger, I'd teach you what life is about. Now you'll have to teach me, or at least remind me.” They both laughed.

He took her out every week, to funny little restaurants on the West Side, or in their neighborhood, or the Village, and sometimes they took the subway to get there. But he always treated her to dinner, despite the fact that he appeared to live on a brutally tight budget, and in deference to that, she was always careful about what she ordered. He complained that she didn't eat enough, remembering what Mrs. Rosenstein had said about her being too thin, and sometimes he made her order more in spite of her protests. And now and then he scolded her for not making any effort to meet young people, but he loved having her to himself, and was happy she didn't.

“You should be playing with children your own age,” he growled at her, and she smiled at him.

“They play too rough. Besides, I don't know any. And I love talking to you.”

“Then prove it to me by doing some writing.” He was always encouraging her, pushing her, and by Thanksgiving, two months after they'd met, she had filled three notebooks with stories. Some of them were excellent, and he told her frequently that thanks to her diligence, he thought her style was improving. He had encouraged her more than once to send her work to magazines, just as Mother Gregoria had, but she seemed to have no inclination to do it. She had far less faith in her writing skill than he did.

“I'm not ready.”

“You sound like Picasso. What's ‘ready’? Was Steinbeck ready? Hemingway? Shakespeare? Dickens? Jane Austen? They just did it, didn't they? We are not striving for perfection here, we are communicating with each other. Speaking of which, my dear, are you going home for Thanksgiving?” They were at a tiny Italian restaurant in the East Village, and she was startled by his question.

“I… no…” She didn't want to tell him there was no home to go to. He knew she had grown up in the convent, but she had never told him clearly that she had no contact with her family at all, and she was no longer welcome in the convent. The only family she had was him now. “I don't think so.”

“I'm happy to hear it,” he said, looking pleased. Mrs. Boslicki made a turkey for them every year, and he had been hoping Gabriella would be there. Only a few of the boarders there still had relatives, and the young divorced salesman had already moved to another city. “I was hoping to share the holiday with you.”

“So was I.” She smiled and went on telling him about her latest story. There was a flaw in the plot and she couldn't quite figure out how to solve it, with violence, or an unexpected romance.

“There's certainly quite a contrast in your options, my dear,” he mused, “although the two are sometimes related. Violence and romance.” His words reminded her of Joe again, and her eyes clouded over but he pretended not to see it. He wondered if she would ever tell him what tragedies she had lived through. For the moment, he was still guessing, but wise enough never to ask her directly. “Actually love is quite violent.” He went on, “It is so painful at times, so devastating. There is nothing worse. Or better. I found the highs and lows equally unbearable, but then again, the absence of them is more so.” It was a sweet, romantic thing for a man his age to say, and she could almost imagine him as a young man, in love with his bride, the youthful hero. But clearly he had been. “And you, Gabriella, I suspect you have found love painful as well. I see it in your eyes each time we touch on the subject.” He said it with the tenderness of a young lover, and touched her hand gently as he said it. “When you can bring yourself to write about it one day, you will find it all less painful. It is a catharsis of sorts, but the process can be brutal. Don't do it until you're ready.”

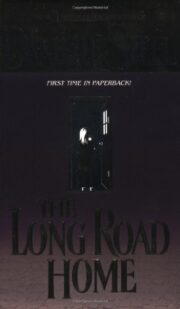

"The long road home" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The long road home". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The long road home" друзьям в соцсетях.