“You gentleman … er … you have been visiting Plymouth?” asked Miss Bell, stating the obvious; but I guessed she wanted to take charge of the conversation.

“On business,” said the younger.

“You must allow us to help you with your luggage when we reach Liskeard,” the elder one said.

“It’s kind of you,” Miss Bell told him, “but everything has been arranged.”

“Well, if you need us … I suppose Miss Tressidor will send her trap to meet you.”

“I understand we are being met.”

Miss Bell’s manner was really icy. She had a notion that perfect gentlemen did not speak to ladies without an introduction. I think the elder one—Paul—was aware of this and amused by it.

Silence prevailed until we came into Liskeard. Paul Landower took my travelling bag and signed to Jago to take Miss Bell’s, and in spite of her protests they came with us to make sure that our luggage was put off the train. The porter touched his cap with the utmost respect and I could see that the Landowers were very important people in the neighbourhood.

My trunk was carried out to the waiting trap.

“Here are your ladies, Joe,” said Paul Landower to the driver.

“Thank ‘ee, sir,” said Joe.

We were helped into the conveyance and we started off. I looked back and saw the Landower brothers standing there looking after us, their hats in their hands, bowing—somewhat ironically, I thought. But I was laughing inwardly and my spirits were considerably lifted by the encounter.

Miss Bell and I sat face to face in the trap, my trunk on the floor between us and as we left the town behind and came into the country lanes, Miss Bell seemed very relieved. I guessed she had regarded the task of conveying me to Cornwall as a great responsibility.

” ‘Tis a tidy way,” our driver Joe told us, “and it be a bony road. So you ladies ‘ud better hold tight.”

He was right. Miss Bell clutched her hat as we went along through lanes where overhanging branches threatened to whisk it off her head.

“Miss Tressidor be expecting you,” said Joe conversationally.

“I hope she is,” I could not help replying.

“Oh yes, ‘er be proper tickled like.” He laughed to himself. “And you be going back again, soon as you’m come, Missus.”

Miss Bell did not relish being called Missus, but her aloof manner had no effect on Joe.

He started humming to himself as he went on through the lanes.

“We’m coming close now,” he said, after we had been going for some time. He pointed with his whip. “Yon’s Landower Hall. That be the biggest place hereabouts. There’s been Landowers here since the beginning of time, my missus always says. But you’m already met Mr. Paul and Mr. Jago. On the train, no less. My dear life, there be coming and going at Landower these last months. It means something. Depend on it. And there’s been Landowers here since …”

“Since the beginning of time,” I put in.

“Well, that’s what my missus always says. Now, there you can see it. Landower Hall … squire’s place.”

I gasped in admiration. It was a magnificent sight with its gatehouse and machicolated towers. It was like a fortress standing there on a slight incline.

Miss Bell assessed it in her usual manner. “Fourteenth century, I should guess,” she said. “Built at the time when people were growing away from the need to build for fortification, and concentrated more on homes.”

“Biggest house hereabouts … and that’s counting the Manor too … though it runs it pretty close.”

“Living in such a house could be quite an experience,” said Miss Bell.

“Rather like the Tower of London,” I said.

“Oh, there’s been Landowers living there for …” Joe paused and I said: “We know. You told us. Since the beginning of time. The first man to emerge from primeval slime must have been a Landower. Or do you think one of them was the original Adam?”

Miss Bell looked at me reprovingly, but I think she understood that I was a little overwrought and more than ever indulging in my habit of speaking without wondering what effect my words might have. During the journey I had still been part of the old life; now the time was coming for a change—a complete change. It is only a visit, I kept telling myself. But the sight of that impressive dwelling and the memory of the two men on the train whose home it was, made me feel that I had moved away from all that was familiar into a new world—and I was not sure what I was going to find in it.

I was overcome by a longing for the familiar schoolroom and Olivia there looking at me with her short-sighted eyes, reproving me for some outspokenness, or with that faintly puzzled look which she wore when she was trying to follow the devious wanderings of my comments.

“Not far now,” Joe was saying. “Landowers be our nearest neighbours. Odd they always says to have the two big houses so close. But ‘tas always been so and I reckon always will.”

We had come to wrought-iron gates and a man came out from a lodge house to open them. I judged him to be middle-aged, very tall and lean with longish untidy sandy hair. He wore a plaid cap and plaid breeches. He opened the gate and took off his cap.

“Thank ‘ee, Jamie,” said Joe.

Jamie bowed in a rather formal manner and said in an accent which was not of the neighbourhood: “Welcome to you, Miss Tressidor … and Madam …”

“Thank you,” we said.

I smiled at him. He had an unlined face and I wondered fleetingly if he were younger than I had at first thought. There was an almost childishness about him; his opaque eyes looked so innocent. I took a liking to him on the spot. As we passed through the gates I had a good look at the gatehouse with its picturesque thatched roof; and then I saw the garden. Two things struck me; the number of beehives and the colourful array of flowers. It was breathtaking. I wanted to pause and look but we were past in a few minutes.

“What a lovely garden!” I said. “And the beehives, too.”

“Oh, Jamie be the beekeeper hereabouts. His honey … ‘tis said to be second to none. He be proud of it and that fond of the bees. I do declare he knows ‘em all. They be like little children to him. I’ve seen the tears in his eyes when any one of ‘em comes to grief. He be the beekeeper all right.”

The drive was about half a mile long and as we rounded the bend we came face to face with Tressidor Manor—that beautiful Elizabethan house which had caused such bitterness in the family.

It was grand—but less so than the one we had just passed. It was red brick and immediately recognizable as Tudor—and Elizabethan at that, because from where we were it was possible to define the E shape. There was a gatehouse, but it looked more ornamental than that of Landower, and it formed the middle strut of the E; two wings protruded at either side. The chimneys were in pairs and resembled classic columns, and the mullioned windows were topped with ornamental mouldings.

We went through the gatehouse into a courtyard.

“Here we be,” said Joe leaping down. “Oh, here be Betty Bolsover. Reckon she have heard us drive in.”

A rosy-cheeked maid appeared and bobbed a curtsey.

“You be Miss Tressidor and Miss Bell. Miss Tressidor ‘er be waiting for ‘ee. Please to follow me.”

“I’ll see to the baggage, ladies,” said Joe. “Here, Betty, go and get one of ‘em from the stables to come and give me a hand.”

“When I’ve took the ladies in, Joe,” said Betty; and we followed her.

We passed through the door and were in a panelled hall. Pictures hung on the walls. Ancestors? I wondered. Betty was leading us towards a staircase, and there standing at the top of it was Cousin Mary.

I knew who she was at once. She was such an authoritative figure; moreover there was a certain resemblance to my father. She was tall and angular, very plainly dressed in black with a white cap on her pepper-and-salt hair, which was dragged right back from a face which was considerably weatherbeaten.

“Ah,” she said. She had a deep voice, almost masculine, and it seemed to boom through the hall. “Come along, Caroline. And Miss Bell. You must be very hungry. Are you not? But of course you are. And you have had an exhausting journey. You can go now, Betty. Come along up. They’ll see to the baggage. There’ll be food right away. Something hot. In my sitting room. I thought that best.”

She stood there while we mounted the stairs.

As we came close she took me by the shoulders and looked at me and although I thought she was going to embrace me, she did not. I soon learned that Cousin Mary was not prone to demonstrations of affection. She just peered into my face and laughed.

“You’re not much like your father,” she said. “More like your mother perhaps. All to the good. We can’t be called a good-looking lot.” She chuckled and released me, and as I had been about to respond to her embrace I felt a little deflated. She turned to Miss Bell and shook her by the hand. “Glad to meet you, Miss Bell. You have delivered her safely into my hands, eh? Come along. Come along. Hot soup, I thought. Food … and then I thought bed. You have to be off again in the morning. You should have had a few days’ rest here.”

“Thank you so much, Miss Tressidor,” said Miss Bell, “but I am expected back.”

“Robert Tressidor’s arrangements, I understand. Just like him. Drop the child and turn at once. He should know you need a little rest after that journey.”

Miss Bell looked uncomfortable. Her code would never allow her to listen to criticism of her employers. I did not feel the same compunction to hear my father spoken of in this way, and I was rather intrigued by Cousin Mary, who was quite different from what I had been imagining.

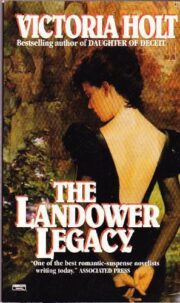

"The Landower Legacy" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Landower Legacy". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Landower Legacy" друзьям в соцсетях.