Occasionally I caught a glimpse of compassion in her eyes when they rested on me. She was sorry for me and that made me sorry for myself. I was angry. I knew that married ladies should not have romantic friendships with dashing cavalry officers; they should not meet them secretly. Yet knowing this, I had betrayed my mother. If only I had not talked to my father! But what else could I have done? Could I have lied? Surely that would not have been right. And he had come upon me so suddenly when I was in my dressing gown and had not had the time to hide my locket.

It was no use going over it. It had happened and because of it my life had been disrupted. Now I was snatched from my home, from my sister, from my parents … well, perhaps that did not matter so much as I saw so little of Mama and far too much—for my comfort—of Papa. But everything was going to be new now, and there is always something alarming about the unknown.

If only I knew everything. I was too old to be kept in the dark; at the same time they considered me not old enough to know the whole truth.

Miss Bell was talking brightly about the countryside through which we were passing.

“This,” I said with a touch of irony, “will be a geography lesson with a touch of botany thrown in.”

“It is all very interesting,” said Miss Bell severely.

We had pulled up at a station and two women came into the compartment—a mother and a daughter, I guessed. They were pleasant travelling companions and when we lapsed into easy conversation they told us that they were going as far as Plymouth and that they made the journey once a year when they visited relatives.

We chatted comfortably and Miss Bell brought out the luncheon basket which Mrs. Terras, the cook, had packed for us.

“You will excuse us,” she said to the ladies. “We left early and we have a long journey ahead.”

The elder of the ladies said how wise it was to come so prepared. She and her daughter had eaten before they left and there would be a good meal awaiting them on their arrival.

There were two legs of cold chicken and some crusty bread. I remembered Waterloo Place with a sudden pang of misery. It seemed far away—in another life.

“It looks delicious,” said Miss Bell. “I’m afraid we shall have to use our fingers though. Dear me!” She smiled at our companions. “You will have to forgive us.”

“It is difficult travelling,” said the elder woman.

“I have a damp flannel which I brought with me, suspecting something like this,” went on Miss Bell.

We ate the chicken and the little cakes which had been provided by a thoughtful Mrs. Terras for our dessert. Miss Bell produced a bottle of lemonade and two small cups. Yet another reminder of Waterloo Place.

I felt rather drowsy and, rocked by the rhythm of the train, dozed. When I awoke I was startled, for a moment wondering where I was.

Miss Bell said: “You’ve had a long sleep. I must have nodded off myself.”

“We’ve come into Devonshire now,” said the younger of the two ladies. “Not much farther for us to go.”

I looked out of the window at the woodlands, lush meadows and the rich red soil. We went through a tunnel and when we emerged, there was the sea. I was enchanted by the sight of the white frilled waves breaking about black rocks. I saw a ship on the horizon and thought of my mother going abroad. Where? When would she come back? When should I see her again? When I did I would ask her why I had been sent away. I know I told my father that we had been to Captain Carmichael’s but it was only the truth, and I know that he saw my locket. But why send me away because of that?

Melancholy descended on me as I wondered what Olivia was doing at that moment.

Our travelling companions were collecting their things together. “We shall soon be in Plymouth,” they said.

“Then,” added Miss Bell, “we shall cross the Tamar and be in Cornwall.”

She was trying to inspire me with enthusiasm. I was interested but I could not stop thinking of Cousin Mary—the harpy—who had to be faced at the end of the journey, and the dreadful knowledge that Miss Bell would go away and leave me there. She had suddenly become very dear to me.

We were coming into the station.

The ladies shook hands and said it had been pleasant travelling with us. We waved goodbye and they went hurrying away to meet someone who was waiting for them.

People were scurrying along the platform. Many were getting off the train and some were getting on. Two men passed and looked in at the window.

Miss Bell sat back in her seat, relieved when they passed on.

“For a moment I thought they were coming in,” she said.

“They scrutinized us and decided against us,” I said with a laugh.

“They probably thought we would prefer to travel with ladies.”

“Very considerate of them,” I commented.

But apparently I was wrong, for just as the guard was blowing the whistle, the door was thrust open and the two very same men came into the compartment.

Miss Bell drew herself back in her seat not at all pleased by the intrusion.

The two men settled themselves in the vacant corner seats, and as the train puffed out of the station I took covert looks at them. One was little more than a boy—I imagined he was two or three years older than I. The other I imagined to be in his early twenties. They were elegantly dressed in frock coats and bowler hats, and these last they took off and laid on the empty seats beside them.

There was something about them which claimed my attention.

They both had thick dark hair and dark heavy-lidded eyes—very bright, as though they missed little. I knew what it was that attracted me. It was a certain vitality; they both seemed as though it were something of an ordeal for them to sit still. I guessed they were related. Not father and son—the difference in age was not great enough. Cousins? Brothers? They had similar strong features—somewhat prominent noses which gave them an arrogant look.

I must have been studying them very intently, for I caught the elder one’s eyes on me and there was a certain glint in them which I did not understand. He might have been laughing at my curiosity—or annoyed by it, I was not sure. In any case I was ashamed of my bad manners, and I flushed slightly.

Miss Bell was gazing out of the window rather studiedly, I thought, as though to indicate that she was unaware of the men. I was sure she believed it rather inconsiderate of them to have come into a compartment where two females were alone.

It was only when we were crossing the Tamar that her instinct for instruction prevailed over her displeasure.

“Just look, Caroline. How small those ships look down there! Now this is the famous bridge built by Mr. Brunei. It was opened in er …”

“Eighteen fifty-nine,” said the elder of the men, “and if you would like the gentleman’s name in full, it was Isambard Kingdom Brunei.”

Miss Bell looked aggrieved and said: “Thank you.”

The man’s lips lifted at the corners. “It has a central pier in the rock eighty feet below high-water mark … if you are thirsting for more knowledge,” he went on.

“You are very kind,” said Miss Bell coolly.

“Proud rather,” said the man. “It is an extraordinary engineering feat, and the climax of that amazing gentleman’s work.”

“Indeed, yes,” remarked Miss Bell.

“An impressive approach to Cornwall,” he went on.

“I am sure you are right.”

“Well, Madam, that you can witness for yourself.”

Miss Bell bowed her head. “We are coming into Saltash,” she said to me. “Now … we are in Cornwall.”

“I say Welcome to the Duchy,” said the man.

“Thank you.”

Miss Bell closed her eyes to indicate that the conversation was at an end and I turned my attention to the window.

We travelled in silence for some time while I was very much aware of the man—particularly the elder one—and I knew Miss Bell was too. I felt faintly annoyed with her. Why did she suspect them of indecorous behaviour towards two unprotected females? The thought made me want to laugh.

He had noticed my lips twitch and he smiled at me. Then his eyes went to my travelling bag on the rack.

“I believe,” he said to his companion, “that this is rather a pleasant coincidence.”

Miss Bell continued to look out of the window, implying that their conversation was of no interest to her and indeed that she could not hear it. I could not attain the same nonchalance—nor could I see why I should pretend to.

“Coincidence?” said the other. “What do you mean?”

The elder one caught my eye and smiled. “Am I right in assuming that you are Miss Tressidor?”

“Why yes,” I replied in some amazement; then I realized that he must have seen my name on the label attached to my travelling bag.

“And you are on your way to Miss Mary Tressidor of Tressidor Manor in Lancarron?”

“But yes.”

Miss Bell was all attention now.

“Then I must introduce myself. My name is Paul Landower. I am one of Miss Tressidor’s close neighbours. This is my brother, Jago.”

“How did you know my charge is Miss Tressidor?” demanded Miss Bell.

“The label on her luggage is clearly visible. I trust you have no objection to my making myself known?”

“But of course not,” I said.

The younger one—Jago—spoke then: “We did hear you were coming to the Manor,” he said.

“How did you know that?” I demanded.

“Servants … ours and Miss Tressidor’s. They always know everything. I hope we shall be seeing you during your stay.”

“Yes, perhaps so.”

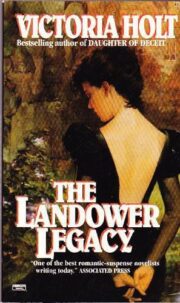

"The Landower Legacy" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Landower Legacy". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Landower Legacy" друзьям в соцсетях.