“What made you do that suddenly?”

“It was something Rosie said. Rosie always had her ears open, I imagine. She’s like me in a way. That’s why we got on. We talked a lot together. I reckon she’s had a life of it. She mentioned this after we’d seen him.”

“Seen him?”

“Jamie McGill. I wanted to get some honey for her to take back to London with her and I said to her, ‘You won’t be able to buy anything like you can get from this man. He’s a magician with the bees and has conferences with them. He’s a little loose in the top storey.’ “

“I wish you wouldn’t talk about him like that. Sometimes I think he’s cleverer than any of us. He’s learned how to be contented and that’s about the wisest thing anyone can do.”

“Well, don’t you want to hear?”

“Of course.”

“I took her along. She was interested in the bees and in him and we stopped and talked awhile. When he left she asked what his name was, and when I told her she said, ‘McGill. I’m sure there was a McGill case.’ Well, as you can imagine, I was all ears. I said to her, ‘There’s always been a bit of a mystery about Jamie McGill. He won’t talk and he got a little fussed when I asked him a few simple questions … just the ordinary sort of ones you might ask anybody.’ Rosie said, ‘Well, I can’t be sure, but there was a case and I’m certain the name was McGill. There wasn’t a lot about it in the London papers because it happened in Scotland.’”

“I think it must have been something to do with his brother,” I said. “He did mention a brother to me once.”

“Yes … that’s right. Rosie remembered that this McGill had been involved in a murder case. She wasn’t sure what happened, but he got off. Then she remembered that it was because he got off that there was this bit of a stir about it. It was a verdict we don’t have here. ‘Not proven.’ That was why it was written about and Rosie remembered. Well, I felt ever so interested … but Rosie didn’t remember anything more.”

“Do you mean to tell me,” I said incredulously, “that you travelled up to Scotland to discover the secrets of Jamie McGill?”

She nodded, her eyes shining with mischief. “Though I’d have gone in any case if I’d known what a lovely little drama I was making here.”

“I believe you like stirring up trouble.”

She was thoughtful. “I’m not sure. I like to know … I always did. I like to find out what people are hiding.”

“And did you find out about poor Jamie McGill?”

“Yes. I talked to people who remembered, and you’re able to get some of the papers which came out years back. I stayed with my friend in Edinburgh and she took me about the town … showing me the ropes. As I said we found quite a number of people who remembered. It wasn’t all that long ago … only ten years or so. People remember these things.”

“Well, what did you discover?”

“It was Donald McGill. I thought it might be Jamie.”

“That,” I said coldly, “was what you hoped to discover.”

“But it was Donald. His brother didn’t come into it at all. There was no mention of him. Donald had murdered his wife.”

“I thought you said it was not proven?”

“I mean he was on trial for murder, but they couldn’t prove him guilty. She was found at the bottom of a staircase in their home. They had been on bad terms and there she was … dead. She had a blow on her head, but they couldn’t tell whether she had got it in falling or if it had been delivered before she was pushed down. That was why they had to decide and they couldn’t, so there was this verdict, ‘Not Proven.’ “

“Congratulations on your discovery,” I said.

“Well, at least you know about the man you employ.”

“But this was his brother.”

“It’s something he doesn’t want to come out.”

“I can quite understand why not. If anything like that happens in your family, I daresay you want to get away from it.”

“I had to know.”

“Well, now you are satisfied.”

“Yes, I’m satisfied now.”

“I hope you won’t go round talking about this. If Jamie wants to keep his secrets he should be allowed to.”

“I don’t suppose I shall say anything, and in any case it is only his brother. Now if he were the murderer …”

“You mean the suspected murderer. It was not proven as I have to keep reminding you.”

“If it had been Jamie that would have been different.”

“A great disappointment for you!”

“I’m still interested in him. I think there is something very odd about him.”

“I should leave him in peace if I were you.”

She looked at me, smiling. “You’re of much greater interest to me, Caroline. When I think of you … coming here, getting the estate and everything … and then getting your own back on Jeremy Brandon … and then falling in love with my husband … I must say there is never a dull moment with you, Caroline.”

“I am astonished that my life is so interesting to you. One thing I ask you. Please don’t upset Jamie by letting him know you have discovered his secret. Remember it is his.”

“Yes,” she said, still smiling. “Let’s all keep our secrets, eh?”

DISCLOSURES

During the days which followed I did not want to meet people. I knew that the great topic of conversation throughout the neighbourhood would be the search of the mine shaft and the return of Gwennie.

I did hear certain comments and it amazed me how those who had been so certain that Gwennie’s body would be found in the mine shaft now declared they had never suspected foul play for one moment and they had guessed all the time that she had gone off somewhere without saying.

I did not go to Landower. I did not want to see Gwennie and I was afraid of seeing Paul. I just wanted to shut myself away for a little while. All that had happened had been a great shock to me and that was partly because I had suspected that Paul, driven beyond endurance, might have killed her. It was a terrible accusation to make against the man one loved; and it taught me something about myself. Even if he had, I should have been ready to shield him.

Because of my immature dreams into which I had set Paul during the time I was growing up, because of my infatuation for Jeremy Brandon, I had sometimes wondered how deep my love for Paul had gone. I was in no doubt now. I loved him for ever and ever.

But our case seemed hopeless and I must come to some decision about my life. I had Livia and I had Tressidor. Livia and I could leave, but could I leave Tressidor? Could I sell it? The ancestral home of the Tressidors. But I was not really one of them. My mother had merely married into the family and my father was not one of them either.

What did I owe Tressidor? I ought to get away. What life could I ever build up here? Moreover there was this niggling fear in my mind. Suppose what I had imagined had happened, actually did. It could so easily I believed, for would it have been so unusual, so unexpected? Many—including myself—had believed it could happen.

These were more grim thoughts.

Cousin Mary, I said to myself, If you are watching me now, if you know what is happening here, you will understand. I know what this place meant to you. I know that you wanted me to carry on … and it was what I wanted. It meant a good deal to me. But I can’t stay here, and I feel that what has happened has been a sort of rehearsal, a warning. It has brought home to me so clearly what could be. How can anyone go on enduring this state of affairs? How near to murder can ordinary people come? Perhaps if they are goaded beyond endurance … Cousin Mary, would you understand?

I thought: I will go to London. I will talk to Rosie … and perhaps Jago. They might help me decide.

Livia wanted to go to Landower to play with Julian. “The two of them are so good together,” said Nanny Loman. “Julian is like a big brother to her. I’ve never seen two play together like those two do.”

So Nanny Loman took Livia over to Landower.

When she came back she found an early opportunity of talking to me.

She said: “Mrs. Landower’s gone off again.”

“Gone off?”

“Off on her travels.”

“Oh, where this time?”

“She hasn’t said.”

“She seems to like these mystery tours. I hope she has taken her comb with her this time. Did you find out?”

“As a matter of fact I did. It appears she has taken it.”

“Then all is well,” I said.

Gwennie had been away a week. I had seen Paul and we went together into the woods where we could talk in peace.

“I wonder where she has gone this time,” I said.

“She was so amused at the last upheaval. I suppose she thought she would do it again.”

“Nobody seems excited about it this time.”

“Well, you can’t play the same trick twice.”

I said: “I’ve been thinking a great deal. I am beginning to wonder whether I ought after all to sell up here and get right away.”

“You can’t do that.”

“I could, and sometimes I think it is the only solution.”

“It’s defeatism.”

“It is a retreat from something which could become intolerable for us all.”

“That last affair shattered you, didn’t it? I think you really believed I had hit her on the head with a blunt instrument and thrown her down the mine shaft.”

I was silent, then I said: “I’m afraid, Paul. This is getting out of hand. She will never let you go.”

“I could leave.”

“Leave Landower … for which you would always crave. It’s different with Tressidor. I wasn’t brought up in it. I’m not even a Tressidor. I just have the name because my mother happened to be married to one. I don’t feel the ties of a home which has always been mine and my family’s.”

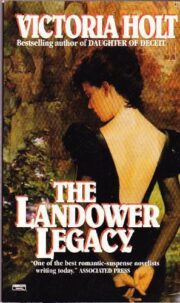

"The Landower Legacy" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Landower Legacy". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Landower Legacy" друзьям в соцсетях.