I was not sure how long we were in the wood, but we knew we must part.

I said: “I am going to ride to the moor.”

“You shouldn’t,” he said.

“I must.”

“I shall go back to Landower,” he said.

“Never forget,” I told him. “Whatever happens, I love you. I will be with you … against all the world if need be.”

“If it took this to make you say that I can’t regret it,” he said.

He held me in his arms for a long time and then we mounted. He went back to Landower and I rode on to the moor.

There were crowds of people there. I saw the men near the mine. They appeared to have finished their task. I looked about me. One of the grooms was standing nearby.

“Is it over, Jim?” I asked.

“Yes, Miss Tressidor. They found nothing … nothing but a few animals … bones and such like.”

Great waves of relief swept over me.

“Looks like a waste of time,” said Jim.

Still people stood about. I wanted to ride back to Landower. I had to see Paul.

I turned my horse and went back as fast as I could.

I did not care what the servants thought. Let them do their worst. Gwennie’s body was not in the mine. They would have to believe that she had got on that train to London.

I knocked at the door. One of the servants opened it. I stared. Someone was coming down the stairs. It was Gwennie.

“Hello, Caroline. This is a joke. Here I am. I gathered you have been wondering what had become of me?”

“Gwennie!” I cried.

“None other,” she said.

“But …”

“I know. I’ve been hearing all about it from Jenny. They’ve been searching the mine, looking for my corpse. What fun!”

“It wasn’t much fun.”

“No. I gathered they suspected my dearly beloved husband. Well, that’ll teach him a lesson. Perhaps he’ll treat me better now.”

Paul had come into the hall.

“She’s come back,” he said.

“Perhaps we ought to go and tell them at the mine,” said Gwennie.

“They had already finished their work,” I said.

“Oh, were you there? Had you gone to see my grisly remains?”

“Certainly not,” said Paul. “She knew you were not there. I had already explained that you had gone off on the train.”

“Poor Paul. It must have been awful for you … that suspicion. I can’t wait to show myself. I’d have loved to arrive at the mine. They might have thought I was the ghost of myself.”

“There was a great deal of consternation when Jenny heard from your aunt that you had not been to Yorkshire.”

“Oh yes … I decided against it at the last moment,” said Gwennie lightly. “I went to see someone I knew in Scotland.”

“What a pity you didn’t say. It would have saved a great deal of trouble.”

“I must say it is rather comforting to know that people round here were so concerned for my welfare. I thought they always looked on me as an outsider.”

“They love drama and you gave them the opportunity to create it,” I said. “They love you for that.”

“I think it’s fun. I’m going out now. To ride round and show myself.”

I said: “Then I’ll leave you to enjoy your fun. Goodbye.”

I went home. I was relieved but far from happy.

The neighbourhood was abuzz with the news: Gwennie was back. It had all been a storm in a teacup. I guessed there were some red faces.

Those who had seen the black dogs and the white hares were suitably subdued. Why should these omens of evil appear just to announce the deaths of a stray sheep and a few animals? And even they had been down there for quite a long time.

Gwennie continued to be greatly amused. She talked of little else. Jenny was shamefaced. She admitted to some of her fellow servants, who reported it to ours so that it came to my ears, that Mrs. Landower did not always wear the comb, and she had mentioned it because she had wanted to know if she had really gone to Yorkshire.

Gwennie came to see me. She said she wanted to talk and could we be alone?

I took her into the winter parlour and sent for some tea, as it was afternoon.

She looked different, I thought, sly in a way.

She began talking about all the fuss of her so-called disappearance.

“Why shouldn’t I go where I want to? As a matter of fact I had no intention of going to Yorkshire. I just said so because it was the first thing I thought of … having my Aunt Grace up there. I didn’t think that fool Jenny would raise all that trouble … on account of a comb.”

“I think the comb was just an excuse.”

“But why should she suspect that something had happened to me?” She laughed. “All the intrigue that’s going on, I suppose. Well, Jenny likes to be in the middle of all that. You can’t blame her. So all this about my comb.”

She took it out of her hair and looked at it. It was tortoiseshell, Spanish type, not large and with little brilliants set in it.

“It’s true I wear it a good deal, but why she should think I would never leave without it, I can’t imagine.”

She stuck it back in her hair.

“So you had other plans right from the first?” I said.

She nodded. “I can’t bear to be in the dark.”

“I know that well.”

“I like to know. It worries me if I don’t. I just have to find out.”

“I did realise that.”

“Yes, everything that goes on. My Ma used to call me Meddlesome Matty. She used to say: ‘Sometimes she’d lift the teapot lid, to see what was within.’ I forget how the rhyme goes on but I believe something terrible happened to Matty. ‘Curiosity killed the cat.’ That was another of my Ma’s sayings. Pa used to laugh at me. ‘It’s no good trying to keep anything from Gwennie,’ he used to say. I knew that it was you and Jago who caused my accident.”

“Oh?”

“Don’t look so startled. I saw you. I remember your green eyes and your hair was all tied up with a ribbon … remember? One day you had it done just like that and I said, ‘Hello, I’ve seen that before.’ It was one of those things that come to you after … you know what I mean. Then I found the door in the gallery and the staircase up to the attics. It didn’t take me long to work that out. I went up there and found the clothes you’d worn. You might have killed me. That was the first thing I had against you.”

“I realised how foolish we were as soon as we’d done it. It was meant to be a joke.”

“Typical of Jago. To frighten us away, of course. Just get rid of us, never mind the consequences.”

“We didn’t think for a moment that you would fall. We didn’t know the rail was rotten.”

“Everything in the house was rotten till Pa and I took it over.”

I was silent.

“I couldn’t walk for a while. I still feel twinges in my back and when I do I say, Thank you, Caroline. Thank you, Jago. It’s all due to you.”

“I am so sorry.”

“All right. You were children. You didn’t think and I know you’re sorry. Jago was always very nice to me. I think it was because of that.”

“Jago was quite fond of you.”

“Landowers are fond of Landower … all the glory of the family. I have to admit I like that, too.”

“I think Jago can’t be accused of those feelings. He was very willing to abandon it all.”

“He’ll be well gilded now. Rosie knows what she’s about.”

“I don’t think he was all that concerned with the gildings.”

“Everybody likes them. They make the wheels go smoothly round.”

“Do they?”

She looked at me sharply. “If you let them,” she said. “I know about Paul, of course.”

“What do you know?”

“That he is after you … and I don’t think you feel much like saying No to him either. But let me tell you this: I’ll never let him go. He married me. Look what he got out of it. He’s got to remember that.”

“He doesn’t forget that he’s married to you.”

“He’d better not. I shall never let him go. You’d better understand that.”

“I do understand it.”

“The best thing you can do is go up to Rosie. She’s fond of you. She’ll help you find a husband and then you won’t have need of someone else’s.”

“There is no need for you to talk in this strain. I understand the position perfectly. I am not looking for a husband, and if I went to London to stay with Jago and Rosie for a visit it would not be with such a hunt in mind.”

“I like your way of talking. Dignity, I suppose you call it. I suppose that is what he likes. Lady of the Manor and so on. Well, it’s not to be, because I’ll never let him go. He’s got the house and he has to take me with it. And that’s how it’s going to stay.”

I said: “Why don’t you try living amicably together?”

“What? With him hating the bargain all the time and trying to wriggle out of it?”

“If you look upon it as a bargain, you’ll never live serenely together.”

“Life’s what it is, Caroline. You take what you want and you pay for it. It’s no use niggling about the price when it’s all signed and settled.”

“I don’t think that is quite the way to look on marriage.”

“And if you go on like this it seems to me you’ll never have an opportunity of looking at it at all.”

“That is very probable,” I said, “and entirely my own affair.”

“Well,” she said, good-natured suddenly, “I didn’t come here to quarrel with you. I know it’s not your fault … or anybody’s fault. It just is. I came to talk to you about something else. As we said, I like to know what’s going on around me. Well, I thought I’d do a little tour of investigation. That’s what I’ve been doing.”

“Where?”

“In Scotland. I went to Edinburgh. I stayed with someone we used to know before we came south. Her father was a friend of my father’s. She married and went to live up in Edinburgh. I thought I’d look her up.”

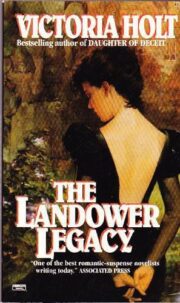

"The Landower Legacy" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Landower Legacy". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Landower Legacy" друзьям в соцсетях.