She never spoke to me again.

The doctor was at the house all next day. There was a hushed gloom everywhere. I could not believe it. Death could not strike twice so soon.

But it could. Olivia was dead. She lay white and still, her face surprisingly young, the lines of anxiety and pain wiped from it. She was the Olivia of my childhood, the sister whom I had patronized, looked down on in some ways, although she was older than I. Nevertheless I had loved her dearly.

If only she would come back, I would take her to Cornwall with me. I would make her forget her perfidious husband, her disillusion with life.

I shut myself in my room. I could not speak to anyone. I felt a deep-rooted sadness which I feared would be with me for the rest of my life.

She must have known she was going to die. I remembered the way she had spoken of death; the certainty with which she had faced it. It was why she wanted to see me; why she had been so insistent that I look after her child.

She had not wanted her to be left to the mercy of a father who might remarry someone who would not care for the child. How much did he care? Was he capable of caring for anyone but himself? Had she feared that Aunt Imogen might take the child? Poor Livia, what a life she would have had! She would be left to the care of Nanny Loman and Miss Bell—kind, worthy people—but Olivia had wanted the equivalent of a mother’s love for her daughter, and she knew there was only one place where she could be sure of that. With me.

As I realized the weight of my responsibility, my terrible melancholy lifted a little. I went to the nursery. I played with the child. I built a castle of bricks with her. I helped her totter along; I crawled on the floor with her. There was comfort there.

The funeral hatchment was placed on the outside wall as it had been at the time of Robert Tressidor’s death, and the ordeal through which I had recently passed in Cornwall had to be faced again here. There were the mutes in heavy black, the caparisoned horses, the terrible tolling of the bell and the procession from the church to the grave.

I caught a glimpse of Rosie as I went into the church. She smiled at me and I was pleased that she had come.

I walked beside Jeremy. He looked sad and every bit the inconsolable husband, and I think my contempt for him helped me to bear my own grief. I wondered cynically how deep his sufferings went and whether he was calculating how much of her fortune would be left to him.

I stood at the graveside with him still beside me and Aunt Imogen on the other side with Uncle Harold. Aunt Imogen was wiping her eyes and I asked myself how she managed to produce her tears. I myself shed none.

Back at the house there was food and drink—the funeral meats, I called them—and after that the reading of the will. Olivia’s wish that I should have the custody of her child was explained.

Everything passes, I consoled myself. Even this day will be over … soon.

There were several family conferences. Aunt Imogen usually took control. She thought it was rather unseemly for an unmarried woman to have charge of a child. What would people say? Whatever explanation was given they would think …

I said: “They may think what they will. But as it is a matter of concern to you, Aunt Imogen, let me remind you that I intend to take Livia with me to Cornwall, and if it is any consolation to you and soothes your fears, there they will all know that it is impossible for her to be my child. I was very much in evidence among them at the time of her gestation and birth, and I am sure that even the most suspicious and scandal-loving would find it very hard to explain how a young woman managed to bear a child while going about the countryside, keeping its existence a secret and somehow smuggling it to London.”

“I was thinking of your future,” said Aunt Imogen, “and however you look at it, it is unsuitable.”

All the same her protests were half-hearted, for she herself did not want to be burdened with the care of Livia.

“And another thing,” she went on, “it seems to be forgotten that Livia has a father.”

“When Olivia asked me, just before she died, she did not mention Livia’s father.”

Jeremy said: “There is no one to whom I would rather trust my daughter than to Caroline.”

“I still think it is irregular,” added Aunt Imogen.

“I shall be leaving for Cornwall very shortly,” I said firmly: “I have written asking them to prepare the nurseries there.”

“They can’t have been in use for ages,” said Aunt Imogen.

“Well, it will be pleasant to use them again. I shall take with me Nanny Loman and Miss Bell … so Livia will not find everything very different around her.”

“Then,” added Aunt Imogen, and I fancied I detected a note of relief in her voice, “there is nothing more we can do.”

I overheard her say to her husband that I had a very high opinion of myself, and I was Cousin Mary all over again. To which he replied, rather daringly, that that was perhaps not such a bad thing in view of my responsibilities. I didn’t wait to hear her comment. I was not interested in Aunt Imogen’s view of me.

I spent a great deal of the rest of my time in London with Livia. I wanted her to get used to me. She did not appear to be aware that she had lost her mother, which was a blessing. I was determined to give her a substitute in myself, in the hope that she would never really know what she had missed.

I played with her; I talked to her; she had a few words; I showed her pictures and built more castles. I crawled about the floor and I was rewarded by the smile which appeared on her little face every time I appeared.

She was helping me to overcome my grief. I did not want to think of death. It seemed to me so cruel that two loved ones should have been taken from me within a few months.

I clung to Livia as I had clung to Tressidor. Worthwhile work was the only solace I could find.

Nanny Loman and Miss Bell were eager to accompany me to Cornwall. They both thought it would be best to get right away.

“She doesn’t know her mother’s gone yet,” said Nanny Loman. “She didn’t see so much of her while she was ill … but she might remember … here. New surroundings are what she needs.”

I believed Nanny Loman was a very sensible woman; and I knew the worth of Miss Bell.

“Death in childbed,” she said, “is no uncommon occurrence, alas. Olivia should never have undergone another pregnancy so soon. It was most unfortunate.”

“She knew, I think.”

“She was not really happy towards the end,” said Miss Bell.

No, I thought, indeed she was not. She must have known he was losing money, for she had murmured something about debts. And Flora Carnaby … she knew of that too. Servants whisper, I supposed. Those things which were not intended for her ears reached her in some way. It could so easily happen.

Before I left Jeremy talked to me.

“Thank you, Caroline. Thank you for all you are doing for Livia.”

“I am doing what Olivia asked me to before she died.”

“I know.”

“She was aware that she was going to die.”

He hung his head, implying that his grief had overcome him. I was sceptical. All the old hatred I had felt for him when he had told me he did not want me without a fortune, swept back.

“I don’t think she was very happy,” I said pointedly.

“Caroline … I shall want to see my daughter sometimes.”

“Oh, shall you?”

“But, of course. Perhaps you will bring her to me … or perhaps I will come to see you.”

“It’s a very long journey,” I reminded him. “And you would find it rather dull in the country.”

“I should want to see my daughter,” he said. “Oh, Caroline, I’m so grateful to you. To be left with a young daughter … I feel so inadequate.”

“You couldn’t be expected to excel in the nursery as I am sure you do in other fields.”

“Caroline, I shall come.”

I studied him intently and thought: Oh yes, he will come.

Was that a certain gleam I detected in his eyes? Now he was looking at me as once he had before. He would see me against the background of a country mansion, and I could see that he found the picture as attractive as it had been once before against another setting—which had however proved without substance. This one was undoubtedly real.

I was amused. Oddly enough he helped to assuage my grief a little. Thinking of him and his motives made me forget for a while the memory of my sister lying cold and lifeless in her bed.

There was great excitement when I arrived in Lancarron with my nursery cavalcade. It was the talk of the place for at least a month.

People called to see the child, to hear the latest about the new arrangements at Tressidor. The nurseries were more spacious than those in the London house and although they had been cleaned and made ready there were new acquisitions needed. I plunged feverishly into the buying of new curtains and equipment, everything that was wanted for a modern nursery. To work hard all day, to go to bed tired so that I was too exhausted to brood was the best thing possible.

My life was doubly full. There were the estate matters which had fully occupied me before but now there was the child as well and I was determined to be the sort of mother to Livia that Olivia would have wished.

I had the excellent Nanny Loman and the ever watchful Miss Bell; but I wanted Livia to have a mother in me, and I spent every possible moment with her. I arranged a meeting between Nanny Loman and the guardian of Julian’s nursery, and it was fortunate that the nannies—as Nanny Loman put it—immediately took to each other. There was hardly a day when Julian was not at Tressidor, or Livia at Landower.

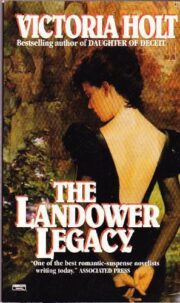

"The Landower Legacy" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Landower Legacy". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Landower Legacy" друзьям в соцсетях.