“Is there anything wrong?”

“It is just that she didn’t really have time to recover from having Livia. It was unfortunate that it should be so soon, and I don’t think she was ever very strong … as you were. However, we’re taking great care.”

“I’ll go to her,” I said.

She was lying in her bed propped up with pillows. I was shocked by the sight of her. Her hair had lost its lustre and there were shadows under her eyes which looked bigger than usual.

They lit up with joy at the sight of me. “Caroline, you’ve come!”

I ran to her and hugged her.

“I came as soon as I could.”

“Yes, I know. It must have been terrible … Cousin Mary … and all the things that happened.”

“Yes,” I said. “It was.”

“And she has left you Tressidor.”

“I must tell you all about it.”

“You’re so clever, Caroline. I was never clever like you.”

“No … I’m not clever … very foolish often. But let’s talk about you. How is my goddaughter?”

“Asleep now, I fancy. Nanny Loman is in charge and Miss Bell, of course.”

“I saw Miss Bell as I came in.” I looked at her anxiously. She was in the last stages of pregnancy and I knew that women change at such times, but should her skin look so waxy, her eyes so enormous with that haunted expression in them. My concern for her was making me forget my grief at the loss of Cousin Mary.

“You must be exhausted after your journey.”

“Not a bit. Just a little grubby.”

“You look wonderful. I always forget how green your eyes are and when I see them they startle me. Caroline, you won’t hurry away, will you?”

“Oh no. I’ll stay as long as I can.”

“Go to your room now … wash and change. I am sure you want to, and we’ll have supper together up here.”

“That would be lovely.”

“All right. Go now, but come back soon. I’ve such lots to say to you.”

I left her and went to the room I knew so well. I unpacked my case and washed in the hot water which had been brought up. I changed and went back to Olivia.

“Come and sit by my bed,” she said.

“I’m sorry I couldn’t come before. I was all ready to depart and there was the accident …”

“Yes, I know. It’s just that I’m worried.”

I looked at her steadily and said: “Yes, I gathered that you were.”

“It’s about Livia.”

“What about her?”

“I want to know that she’s all right.”

“Is there anything wrong with her?”

“No. She’s a healthy, lively child. There’s nothing wrong with her. I just wanted to make sure that if anything happened to me she’d be all right.”

“What do you mean … anything happened to you?”

A terrible fear was clutching at my heart. I had just come face to face with death. I did not want to meet it again … ever.

“I just meant that … if anything happened to me.”

I was angry suddenly, not with her, but with fate. I said: “When people use that expression they mean Death. Why don’t they say what they mean?”

“Oh, Caroline, you are so vehement. You always were. You’re right though. I mean I’m worried that if I died … what would happen to Livia?”

“How absurd to talk about dying. You’re young. There’s nothing wrong. People have babies every day.”

“Don’t be angry. I just want your assurance. You’re her godmother. I should want you to take her. Now that you own all that property … now you’re a rich woman … you could do it. In any case I would have made provisions for her … and for you … so that you could be together. I’ve had it all done by the solicitors, but I’m glad you’re rich now, for your own sake.”

“Is that what you wanted to say to me?”

She nodded.

I was dumbfounded. I had known there was something, but I had thought it was Jeremy’s extravagances. This was quite unexpected.

“Oh, Olivia, what gave you this idea?”

“Childbearing is an ordeal. I just thought …”

“Don’t hedge with me,” I said sternly. “Tell me the truth.”

“I’ve had a bad time, Caroline. They say it shouldn’t have happened … so soon. I’ve spent most of the time in bed. I just have a feeling that something is going to happen … I mean that I might die.”

“Olivia, that’s no way to face all this.”

“I thought you believed in facing up to reality.”

“But what makes you say this?”

She touched her breast and said: “Something in here.”

I stared at her in dismay and she went on: “I wouldn’t have any qualms about leaving Livia to you. I have complete confidence in you. You’d be better for her than I …”

“Nonsense. No one’s as good as a mother.”

“I don’t think that is always so. I’m too tired to be with her. I’m soft and foolish. You’d be better for her and you would love her too. She is very lovable.”

“Stop it,” I cried. “I won’t listen. All this talk of death is silly. I’ve had enough of death. I’ve lost someone very dear to me. I won’t consider losing another.”

“Oh, Caroline, I’m so glad you’ve come and we won’t talk about it any more. Just give me your word. You will take Livia, won’t you?”

“I don’t want to talk of such …”

“Promise and I’ll say no more.”

“Well, of course, I would.”

She took my hand and pressed it. “I feel contented now. Tell me about Cornwall. Not about the funeral but after and before all that. All those people … Jago and Paul Landower and the man with the bees.”

I sat by her bed talking. I tried to be amusing. It was not easy, because when I thought of the light-hearted days before Cousin Mary’s death I was reminded forcibly that she was no longer there.

But Olivia delighted in my presence and that comforted me. We had a little supper in her room and when her face was animated she looked more like her old self.

I said goodnight to her and went down to see Aunt Imogen who was asking for me.

She greeted me with a little more respect than I remembered before and she looked less formidable than she had in the past. Whether this was because she was getting older or because I was a person of consequence now, I was not sure. Uncle Harold was with her—self-effacing as ever and very cordial.

“How are you, Caroline?” asked Aunt Imogen. “You must be very pleased with the way everything has turned out.”

“I am still mourning Cousin Mary,” I reminded her coldly.

“Yes, yes, of course. So you have become a very rich woman.”

“I suppose so.”

Uncle Harold said: “I believe that you and Cousin Mary were very fond of each other.”

I smiled at him and nodded.

“She was a forthright woman,” he said.

“She had no right to Tressidor, and of course it should have come to me,” said Aunt Imogen. “I am the next of kin. I could, of course, contest the will.”

Uncle Harold began: “No, Imogen. You know …”

“I could contest the will,” she repeated. “But well … we have decided to let sleeping dogs lie.”

“It was Cousin Mary’s wish that I should inherit,” I said. “She taught me a great deal about the management of the estate.”

“It seems wrong for a woman,” put in Aunt Imogen.

“For you too then?” I asked.

“I have a husband.”

Poor Uncle Harold! He looked at me apologetically.

“I can assure you, Aunt Imogen, that the estate, far from suffering under the management of Cousin Mary, improved considerably. I intend that it shall continue to do so under mine.”

I thought Uncle Harold was going to break into applause, but he remembered the presence of Aunt Imogen in time.

I said: “I am anxious about Olivia. She does not seem well.”

“She is in a delicate condition,” Aunt Imogen reminded me.

“Even so, she seems rather weak.”

“She was never strong.”

“Where is her husband?”

“He will be here soon, I imagine.”

“Is he out every night?”

“He has business.”

“I should have thought he would have wanted to be with his wife at such a time.”

“My dear Caroline,” said Aunt Imogen with a little laugh, “you have lived with Cousin Mary, a spinster, and you are one yourself. Such do not know very much about the ways of husbands.”

“But I do know something about the consideration of one human being towards another.”

I enjoyed sparring with Aunt Imogen and having Uncle Harold looking on like some referee who would like to give the points to me if he dared.

Her attitude towards me amused me. She disapproved of me, but as a woman of property I had risen considerably in her estimation; and although she deplored the fact that I had taken Tressidor from its rightful owner, she admired me for doing so.

But I could see that I should not get any real understanding of Olivia’s state of health from her, and I decided that in the morning I would question Miss Bell.

I retired to bed soon after that, but I did not expect to sleep.

I could not throw off my melancholy.

I had just emerged from the tragedy of Cousin Mary’s death to be presented with the possibility of Olivia’s. But she had let her imagination run on, I tried to assure myself. She just had pre-confinement nerves, if there were such things, and I was sure there were. To face such an ordeal so soon after having gone through the whole thing such a short while before was enough to frighten anyone … especially someone as nervous as Olivia.

I tossed and turned and found myself going through all the drama of Cousin Mary’s accident, and then coming back to Olivia.

It was a wretched night.

In the morning I came face to face with Jeremy. He looked as debonair as ever.

“Why, Caroline,” he cried, “how wonderful to see you!”

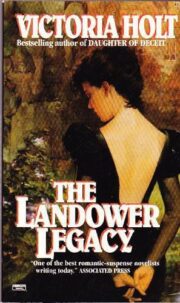

"The Landower Legacy" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Landower Legacy". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Landower Legacy" друзьям в соцсетях.