“We have talked of marriage now and then. I should have liked to see you a happy wife and the mother of children. I suppose that would be reckoned the ideal state. You need a very special sort of man. One, if I may say so, who will direct you to a certain extent and to do that he will have to be very wise and strong as well. He will have to be someone you can respect. Remember that, dear Caroline.

“Now I have finished sermonizing.

“Goodbye, my child. That is how I think of you … the daughter I never had. If I had had one I should have liked her to be exactly like you.

“I thought you should be prepared for all this when they read the will. It might have been a shock to you.

“There is one other thing I have to say to you and that is, don’t grieve for me. Remember this is the best thing that could have happened since poor old Caesar tripped over that tree trunk. I couldn’t have gone on like that. Much better for me to go while I could do so with some dignity and a certain self respect.

“Thank you for being to me what you have. Try to be happy. I’m not much given to poetry as you know but there is something I came across the other day. Shakespeare, I think—and it expressed more beautifully, more poignantly than I could have believed possible all that I want to say to you about my passing. This is it:

” ‘No longer mourn for me when I am dead Than you shall hear the surly sullen bell Give warning to the world, that I am fled From this vile world, with vilest worms to dwell.

Nay, if you read this line, remember not The hand that writ it; for I love you so That I in your sweet thoughts would be forgot If thinking on me then should make you woe.’

“Your Cousin Mary.”

I was in a daze of misery. I knew I should have been prepared for Cousin Mary’s death but it was a bewildering shock. I was grateful that there was so much to do and the weight of my new responsibilities in some measure helped me through the days.

The dismal tolling of the bell on the day they laid her in her grave seemed to go on and on in my head; and what it signified filled me with utter despair. I missed her in so many ways. I wanted to talk to her of things which happened. Sometimes it was hard to believe that I should never see her again. I went over little incidents in my mind from the first day when I had arrived from London with Miss Bell and remembered in what awe I had held Cousin Mary until I had understood those human qualities and the friendliness which had reached out to a lonely child.

I did not weep for Cousin Mary. Sometimes I thought my grief went too deep for tears. I went through it all as though in a hideous nightmare; the falling of clods on the coffin, the mourners round the grave, the return to the house and the solemn reading of the will, the new way in which people now regarded me.

I was Mistress of Tressidor—but there was little joy in that.

That would come. It was almost as though Cousin Mary was commanding me. I kept saying over and over to myself the lines she had quoted. She meant that. I must try to stop grieving. I must give my attention to what really mattered. It was her life and she was passing it on to me.

Jim Burrows came to see me and very movingly pledged himself to support me and to work for me in the whole-hearted manner in which he had worked for Cousin Mary.

I rode round the estate and saw the tenants.

It was gratifying. Many of them said, in various ways, that they welcomed me as the new mistress. They knew everything would go on as before. They would have been apprehensive of a newcomer.

I thought then of Aunt Imogen and the terror she would have struck into them and for the first time since Cousin Mary’s death, I managed to smile.

The estate was my salvation. I would work for it and it would soothe my sorrows. I would make sure that Tressidor prospered and that Cousin Mary, if she could know what was happening, would not be displeased with me.

Gwennie came over to condole. “My word,” she said, “you’ve come into a nice little packet.”

Her eyes glistened acquisitively, as I was sure she tried to calculate the value of the estate.

I was cool with her and she did not stay long.

Paul’s reaction was different. “It means,” he said, “that you can’t go away. You’ll stay with us now … forever.”

Yes, I thought. That was what it meant. My grief had thrust the thought of my future—except with the estate—right out of my mind. I wondered what it could possibly hold for Paul and me. Years of frustration … or perhaps slipping into temptation. People are frail. They mean to behave honourably but they are caught off guard and the barriers are down. What then?

Who could say?

Jago was more solemn than I had ever seen him. He seemed to understand my grief but he did not dwell on it.

His comment was similar to that of Paul. “It’s good to know we’ve got you here for keeps. It was right that she should leave it all to you. You deserve it.”

I was very eager that everyone on the estate should be assured that the future should be as safe for them as I could make it. I visited them all and, of course, Jamie McGill at the lodge.

I said: “I want you to know, Jamie, that I am not making any changes. I want everything to go on as before.”

“I knew it would be like that, Miss Caroline. I reckon this is the best thing that could have happened since we had to lose Miss Tressidor. We’ve got another Miss Tressidor who is as good a lady as the first one.”

“I’m glad you feel that.”

“And it is right and proper the way it has worked out.”

“Thank you, Jamie.”

“I told the bees. They know. They know there’s death about and they’re glad the place has come to you.”

I smiled at him wanly.

“There’s a terrible sadness all around,” he said. “I canna see for it. I saw death coming. I knew there’d be a death.”

“So you see these things, Jamie?”

“Sometimes I see them. I don’t talk of them. People laugh and say you’re crazy. Perhaps I am. But I saw death as plain as you’re sitting there. And I feel it still.”

I said: “Death is always somewhere … like birth. People come and go. That’s the pattern of life.”

He nodded. “Sometimes it goes in threes,” he said. “I’ve seen it work that way. Miss Tressidor she was here … her lovely self one day and then … her horse throws her and that’s the end.”

“That is life.”

“And it’s death, too. I go cold thinking of death. Where will it strike next? Who can say?”

He looked dreamily into the future.

I rose and said I must go.

He came to the door with me. He had changed. He looked happier now.

The flowers in the garden made a riot of colour and the air was filled with their scent and the buzzing of the bees in the lavender.

There was a letter from Olivia. She was so sorry about Cousin Mary’s death, for she knew how much I had cared for her, and she was amazed that Tressidor had been left to me.

“I’m sure you deserve it,” she wrote, “and I am sure you will make a success of it. But it does seem an enormous inheritance. You’re clever though, different from me. You’ll be as good managing it as Cousin Mary was. Aunt Imogen says it is madness and ought to be stopped. She has been to solicitors and they have warned her against taking action. She is furious that nothing can be done about it. But I am glad for I am sure it is best the way it is, although I know how you must be grieving for Cousin Mary.

“I am getting near my time. Do try to come and see me, Caroline. I do particularly want to see you. I have a reason. Could you come soon. It is rather pressing. It means a great deal to me.

“Your loving sister, Olivia.”

Again that plea. I knew there was something she had to tell me. Why did she not write it? Perhaps it was too intimate. Perhaps it was something she did not want to put on paper.

I had a conference with Jim Burrows. I told him that I was worried about my sister and I wanted to go to her. I could postpone it until after the birth of her child but I rather fancied she wanted to see me before.

Jim Burrows said everything would be in order and I could safely leave him in charge.

I should make my arrangements and go.

THE REVENGE

When I arrived in London there was a great deal of excitement over the coming wedding of the Duke of York to Princess Mary of Teck, who had been betrothed to the Duke’s brother, Clarence.

Everyone was talking about the “love match” which had been switched to the living prince when his elder brother had died—some with innocent conviction, others with wily cynicism.

But whatever they felt, everyone was determined to make the most of the royal occasion, and London was crowded with visitors and the street vendors were already out in force to sell their souvenirs of the wedding.

I could never enter the house without a certain emotion. So much of my childhood was wrapped up in it. Miss Bell met me at once.

She said: “I’m glad you’ve come, Caroline. Olivia is longing to see you. You will find her changed a little.”

“Changed?”

“She has had a bad time during her pregnancy. It was too soon.”

“Well, it will soon be over now. The baby is due.”

“Any time now.”

“Shall I go straight to her?”

“That would be the best. You can go to your room after … your old room, of course. Lady Carey is in the house.”

I grimaced.

“She has been here for some weeks. So has the midwife.”

“And, er … Mr. Brandon?”

“Yes, yes. We’re all a little anxious, but we don’t want Olivia to know.”

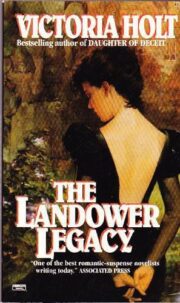

"The Landower Legacy" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Landower Legacy". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Landower Legacy" друзьям в соцсетях.