Jock Carmichael told us about the Army and what it was like to serve in it. He had been overseas many times and expected to go to India. He looked at our mother and a faint sadness touched them both —but that was for the future and seemed too far away to worry about.

He was an old friend of the family, he told us. “Why, I knew your mother before you were born.” He looked at me when he said that. “And then … I was sent to the Sudan, and I didn’t see any of you for a long time.” He smiled at my mother. “And when I came back it seemed as if I had never been away.”

Olivia was having difficulty in keeping her eyes open. I felt the same. A dreamy contentment was creeping over me, but I fought hard against sleep, as I did not want to lose a moment of that enchanted afternoon.

Then the street life burst forth. A hurdy-gurdy had appeared and was playing tunes from The Mikado and The Pirates of Penzance. People started singing and dancing; the hurdy-gurdy was rivalled by a one-man band, a versatile performer who carried pan-pipes fixed under his mouth, a drum on his back—to be beaten by a stick tied to his elbows; cymbals on his drum were clashed by a string attached to his knees; and he carried a triangle. The dexterity with which he performed won the great admiration of all, and the pennies rattled into the hat at his feet.

There was one man selling pamphlets. “Fifty Glorious Years,” he called. “Read about the Life of Her Majesty the Queen.” There were two gipsy women, dark-skinned with big brass earrings and red bandanna handkerchiefs tied about their heads. “Read your fortune, ladies. Cross the palm with silver and a fine fortune will be yours.” Then came the clown on stilts—a comical figure who made the children scream with delight as he stumped through the crowds, so tall that he could bring his hat right up to the windows. We dropped coins into it; he grinned and bowed—no mean feat on stilts—and hobbled away.

It was a happy scene—everyone intent on enjoying the day.

“You see,” said Captain Carmichael, “how impossible it would be to get through the streets just yet.”

Then the tragedy occurred.

Two or three horsemen had made a way for themselves through the crowds who good-naturedly allowed them to pass through.

At that moment another rider came into the square. I knew enough about horses to see at once that he was not in control of the animal. The horse paused a fraction of a second, his ear cocked, and I was sure that the masses of people in the square and the noise they were creating alarmed him.

He lifted his front legs and swayed blindly; then he lowered his head and charged into the crowd. There was a shout; someone fell. I saw the rider desperately trying to maintain control before he was thrown into the air. There was a hushed silence and then the screams broke out; the horse had gone mad and was dashing blindly through the crowds.

We stared in horror. Captain Carmichael made for the door, but my mother clung to his arm.

“No! No!” she cried. “No, Jock. It’s unsafe down there.”

“The poor creature has gone wild with terror. He only needs proper handling.”

“No, Jock, no!”

My attention had turned from the square to those two—she was clinging to his arm, begging him not to go down.

When I looked again the horse had fallen. There was chaos. Several people had been hurt. Some were shouting, some were crying; the happy scene had become one of tragedy.

“There is nothing, nothing you can do,” sobbed my mother. “Oh, Jock, please stay with us. I couldn’t bear …”

Olivia, who loved horses as much as I did, was weeping for the poor animal.

Some men had arrived on horseback and there were people with stretchers. I tried not to hear the shot as it rang out. I knew it was the best thing possible for the horse who must have injured himself too badly to recover.

The police had arrived. The streets were cleared. A hush had fallen on us all. What an end to a day of rejoicing.

Captain Carmichael tried to be merry again.

“It’s life,” he said ruefully.

It was late afternoon when the carriage took us home. In the carriage my mother sat between Olivia and me and put an arm around each of us.

“Let’s remember only the nice things,” she said. “It was wonderful, wasn’t it … before …”

We agreed that it had been.

“And you saw the Queen and all the Kings and Princes. You’ll always remember that part, won’t you? Don’t let’s think about the accident, eh? Don’t let’s even talk about it … to anyone.”

We agreed that would be best.

The next day Miss Bell took us for a walk in the Park. Everywhere there were tents for the poor children who were gathered there—thirty thousand of them, and to the strains of military bands each child was presented with a currant bun and a mug of milk. The mugs were a gift to them—Jubilee mugs inscribed to the glory of the great Queen.

“They will remember it forever,” said Miss Bell. “As we all shall.” And she talked about the Kings and Princes and told us a little about the countries from which they came, exercising her talent for turning every event into a lesson.

It was all very interesting and neither Olivia nor I mentioned the accident. I heard some of the servants discussing it.

” ‘ere, d’you know. There was a terrible accident … near Waterloo Place, they say. An ‘orse run wild … ‘undreds was ‘urt, and had to be took to ‘ospital.”

“Horses,” said her companion. “In the streets. Ought not to be allowed.”

“Well, ‘ow’d you get about without ‘em, eh?”

“They shouldn’t be allowed to run wild, that’s what.”

I resisted the temptation to join in and tell them that I had been a spectator. Somewhere at the back of my mind was the knowledge that it would be dangerous to do so.

It was late afternoon. My mother, I think, was preparing for dinner. There were no guests that evening, but even so preparations were always lengthy—guests or no guests. She and my father would dine alone at the big dining table at which I had never sat. Olivia reminded me that when we “came out,” which would be when we were seventeen, we should dine there with our parents. I was rather fond of my food and I could not imagine anything more likely to rob me of my appetite than to be obliged to eat under the eyes of my father. But the prospect was so far in the future that it did not greatly disturb me.

It must have been about seven o’clock. I was on the way to the schoolroom where we had our meals with Miss Bell—we always partook of bread and butter and a glass of milk before retiring—when to my horror I came face to face with my father. I almost ran into him and pulled up sharply as he loomed up before me.

“Oh,” he said. “Caroline.” As though he had to give a little thought to the matter before he could remember my name.

“Good evening, Papa,” I said.

“You seem in a great hurry.”

“Oh no, Papa.”

“You saw the procession yesterday?”

“Oh yes, Papa.”

“What did you think of it?”

“It was wonderful.”

“It is something for you to remember as long as you live.”

“Oh yes, Papa.”

“Tell me,” he said, “what most impressed you … of everything you saw?”

I was nervous as always in his presence and when I was nervous I said the first thing which came into my head. What had impressed me most? The Queen? The Crown Prince of Germany? The Kings of Europe? The bands? The truth was that it was that poor horse which had run amok, and before I had realized it I had blurted out: “It was the mad horse.”

“What?”

“The er—the accident.”

“What accident?”

I bit my lip and hesitated. I was remembering that my mother had implied that it would be better not to talk of it. But I had gone too far to retract.

“The mad horse?” he was repeating. “What accident?”

There was nothing for it but to explain. “It was that horse which ran wild. It hurt a lot of people.”

“But you were nowhere near it. That happened in Waterloo Place.”

I flushed and hung my head.

“So you were in Waterloo Place,” he said. “That was not as I thought.” He went on murmuring: “Waterloo Place. I see … I think I see.” He looked different somehow. His face had turned very pale and his eyes glittered oddly. I should have thought he looked bewildered and a little frightened, but I dismissed the thought; he could never be that.

He turned away and left me standing there.

I went to the schoolroom. I had done something terrible, I knew.

I was beginning to understand. The manner in which we had gone there in the first place when we thought we were going somewhere else … it was significant, the way Captain Carmichael had been expecting us, the looks he and my mother exchanged …

What did it mean? I knew the answer somewhere at the back of my mind. There are things the young know … instinctively.

And I had betrayed them.

I could not speak of it. I drank my milk and nibbled my bread and butter without noticing what I was doing.

“Caroline is absent-minded tonight,” said Miss Bell. “I know. She is thinking of all she saw yesterday.”

How right she was!

I said I had a headache and escaped to my room. Miss Bell usually read with us, each taking turns for a page—for half an hour after supper. She thought it was not good for us to go to bed immediately after taking food, however light.

I thought I would get into bed and pretend to be asleep when Olivia came up, so that I should not have to talk to her. It was no use sharing suspicions with her. She would refuse to consider them—as she always did everything that was not pleasant.

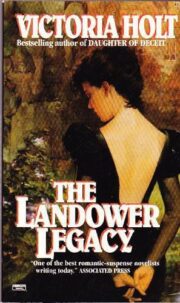

"The Landower Legacy" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Landower Legacy". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Landower Legacy" друзьям в соцсетях.