“But it didn’t work out like that.”

“No, because of a certain incident. Gwennie said, ‘I must see that wonderful old minstrels’ gallery.’ She went up there on her own. I was in the hall with her father …”

“Yes,” I said faintly.

“Something happened in the gallery. Two people played a trick.”

“Oh?”

“Yes. I was in the hall, remember. When she screamed, I looked up. I was just in time to see what Gwennie saw. There was someone there … someone whom I recognized.”

I felt my heart begin to beat very fast. Paul leaned towards me and put his hand on it.

“It’s racing,” he said. “I know why. Do you know if that incident hadn’t happened the Artwrights would have gone away. They told me this afterwards. They liked the house but were appalled by its condition. He was too shrewd to see it as a good proposition. Yes, they would have gone away and we should never have seen them again … but for the ghosts in the gallery. The ghosts are not blameless in this.”

“So … you knew …” I said.

“I saw you … you particularly. I know now that Jago was with you. I know what your motives were … his rather, and you were helping him. I have been up to the attics and seen the clothes you wore. You see even then I was very much aware of you … dancing in and out of my life, the mischievous little girl indulging in a prank with my young brother. But for you … it would have been different.”

“I didn’t force you into marriage.”

“But you were in a way responsible for bringing it about.”

“Does Jago know … you know?”

“No. There’s no point in telling him. Moreover at the time we didn’t want the Arkwrights suing us—with even more reason than they had already. We looked after Gwennie and she and her father stayed at the house. They became enamoured of it and then they had to buy it and the idea came to them that …”

“They should buy the squire as well. A bonus with the house.”

He put his hand over mine and held it fast. “I’m telling you that you are in part responsible. You are involved in this, Caroline. Doesn’t it show how we can all do foolish things and wish we could have another chance. Knowing what you know, would you have gone up to the attics and played ghosts?”

I shook my head.

“Then understand. Caroline, understand me, the position I was in. My home … my family … everything I have been brought up with … it all depended on me.”

“I have always understood,” I said. “I have always known it was the way of the world. But I want to get away from it. I don’t want to be involved. I’ve been hurt and humiliated once and I am determined that it shall not happen again.”

“Do you think I would hurt or humiliate you? I love you. I want to care for you, protect you.”

“I can protect myself. It is something I am learning fast.”

“Caroline, don’t shut me out.”

“Oh Paul, how can I let you in?”

“We’ll find a way.”

I thought, What way is there? There is only one, and I must never allow my weakness, my passion for him, my love perhaps, to lead me down that path.

Yet I sat there and he kept my hand in his. I looked to the horizon where the stark moorland met the sky and I thought, Why did it have to be like this?

We were startled by the sound of horse’s hoofs in the distance. We scrambled to our feet. A trap drawn by a brown mare was coming across the path not far from us. I recognized the trap and horse and then the driver.

I said: “It’s Jamie McGill.”

He saw us and brought the horse to a standstill. He descended and the Jack Russell leaped out of the trap and started to scamper across the moor.

Jamie took off his cap and said: “Good-day, Miss Caroline … Mr. Landower.”

“Good-day,” we said.

“I’m just coming from the market gardens,” he went on. “I’ve been buying there for my garden. Miss Tressidor gives me leave to take the trap when I’ve a load to carry. Lionheart looks forward to a run on the moors when I come this way. He’s been asking for it as soon as we touched the edge of the moor.”

I said: “Mr. Landower and I met by chance over there by the mine.”

“Oh, the mine.” He frowned. “I always say to Lionheart, ‘Don’t go near the mine.’ “

“I hope he’s obedient,” said Paul.

“He knows.”

“Jamie believes that animals and insects understand what’s going on, don’t you, Jamie?”

He looked at me with his dreamy eyes which always seemed as though they were drained of colour.

“I know they understand, Miss Caroline. At least mine do.” He whistled. The dog was dashing along not far from the mine. He stopped in his tracks and came back, jumping up at Jamie and barking furiously.

“He knows, don’t you, Lion? Go on … five minutes more.”

Lionheart barked and dashed off.

“I wouldn’t go riding too near that mine, Miss Caroline,” said Jamie.

“I was giving her the same advice,” added Paul.

“There’s something about this place. I can feel it in the air. It’s not good … not good for beast or man.”

“I have been warned about the ground close to the mine being unsafe,” I told him.

“More than that, more than that,” said Jamie. “Things have happened here. It’s in the air.”

“They were mining tin here until a few years ago, weren’t they?” I asked.

“It’s more than twenty years since the mine was productive,” said Paul. I sensed his impatience. He wanted to get away from Jamie. “I daresay the horses are getting restive,” he said. He looked at me. “I think I am going your way. I suppose you are going back to the Manor?”

“Well, yes.”

“We might as well go together.”

“Goodbye, Jamie,” I said.

Jamie stood with his cap off and the wind ruffling his fine sandy hair, as I had seen him so many times before.

As we walked away I heard him whistling to his dog.

Then his voice said: “Time for us to go, Lion. Come on now, boy.”

Paul and I rode on in silence.

Then I said: “I don’t think Jamie will talk.”

“About what?”

“Seeing us together.”

“Why should he?”

“Surely you know that people thrive on gossip. They will be inventing scandal about you and me … and I should hate that.”

He was silent.

“But I think Jamie is safe,” I went on. “He is different from everyone else.”

“He’s certainly unusual. There’s something almost uncanny about him … coming along like that.”

“It was a perfectly reasonable way of coming along. He’d been to get things for his garden and was using the trap to bring them back.”

“I know … but stopping like that.”

“It was because he saw us and was being polite. He has good manners. Besides, he’d promised the dog he should have a run.”

“All that talk about the mine … and then letting the dog run loose there.”

“He thinks the dog would sense anything strange before we did. Is that what you mean by uncanny?”

“I suppose so. Heaven knows there’s been enough gossip about the mine. White hares and black dogs are said to be seen there.”

“What are they?”

“They are supposed to herald death. You know what people are. I always thought it was a good thing to scare people off going there. There could be an accident.”

“Well, then Jamie is doing what you wish.”

As we rode on Paul said: “I must see you again … soon. There is so much more to say.”

But I could not see that there was anything more to say.

It was too late. And nothing we could say could alter anything that had gone before.

I loved Paul, but I had no doubt now that my love must be put aside.

I had begun to believe that happiness was not for me.

Everything had changed now that Paul had revealed his feelings to me and I was afraid that, in spite of my resolve, I had been unable to hide my response.

I was excited and yet dreadfully apprehensive. I dared not think of the future and more and more I told myself I ought to get away. I even thought of writing to the worldly-wise Rosie and putting the case to her and perhaps hinting that I might come and work for her. Oh, what use would I be among the exquisite hats and gowns? I could learn perhaps. I even thought of taking up Alphonse’s invitation. It was not really very appealing. Moreover I knew that Cousin Mary was relying on me more and more. I very often went out alone visiting the various farms, and Jim Burrows had a great respect for me. There was a great deal to learn about the estate, of course, but as Cousin Mary said, I had a knack of getting on with people, a quality for which the Tressidors were not renowned. She herself, with the best of intentions, was too brisk, too gruff; but I was able to hold the dignity of my position and at the same time show friendliness. “It’s a great gift,” said Cousin Mary approvingly, “and you have it. People are contented, I sense that.”

How could I leave Cousin Mary when she was “like a bear with a sore head” when I was away?

It was comforting to be wanted, to know that I was becoming a success in the work I had undertaken; and yet at the back of my mind was the nagging certainty that by staying I was courting disaster.

I must think about it, I told myself, and the weeks passed.

I often went to Jamie’s cottage. I found such peace there. He now was tending a baby bird which had fallen out of a nest and which he was feeding until it was ready to fly. He kept it in a home-made nest—a coconut shell lined with flannel. I liked to watch him thrusting food into the little creature’s ever-open mouth as he muttered admonitions, warning it about too much greed and gobbling too fast.

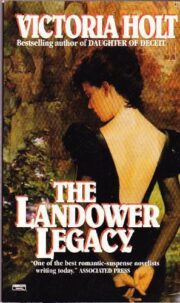

"The Landower Legacy" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Landower Legacy". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Landower Legacy" друзьям в соцсетях.