“Don’t forget I shall want to know all about my goddaughter.”

“You shall,” said Olivia dimpling.

“And … about you yourself,” I added.

She nodded. “And in return I want to hear about those amusing people you meet down there.”

“And don’t hesitate to write about anything … just anything. If something goes wrong …”

“What do you mean?”

“Well, you never know. You often used to keep things to yourself. I want you to tell me if anything worries you.”

“Nothing is going to worry me.”

“But if it should, you will?”

“Yes, I will.”

“And write and let me know everything that Livia does. First smile. First tooth.”

“Too late for the first smile.”

“All the rest then.”

“I promise. And do come again soon.”

“Yes, I will. And wouldn’t it be fun if you came to Cornwall?”

“Perhaps when Livia is older.”

So we talked and I consoled myself that Jeremy could not be losing a great amount of money, otherwise she must surely know.

Jago left at the same time as I did and the journey back passed speedily and pleasantly. Joe was waiting for me.

“Miss Tressidor ‘ave missed ‘ee something terrible, Miss Caroline,” he told me. “She have been as touchy as a bear with a sore head. You can guess what she’s been like.”

“I have never known a bear … let alone one with a sore head.”

“You’re a funny one, you are, Miss Caroline. Proper touchy, she’s been. All happy today though. I see Mr. Jago was on the train with you. He’s been away as long as you have.”

“Oh?” I said noncommittally.

I wondered how soon that information would be passed round.

“Reckon he’s been to Plymouth. Still a bit of to-ing and fro-ing with them Landowers. Mind you, it ain’t like it was afore they come into the money.”

I thought: I am indeed back, back to local speculation and gossip, back to a situation which I must keep in hand.

As we passed Landower I wondered whether Paul had noticed my going and how he had felt about it. Suppose I went back to London. Perhaps I could help Rosie sell her hats. I should think that would be an eventful career.

How amusing … the daughter of the house—who had turned out to be no true daughter—going to work for the parlourmaid—who was no true parlourmaid.

Things were not always what they seemed.

Did I want to go away? No. I should hate to. I wanted to be free with Cousin Mary and why not admit it? With the chance of seeing Paul Landower and dreaming—and hoping—that we could pass together out of this unsatisfying state in which we found ourselves.

Cousin Mary was waiting for me. There was no mistaking her joy in my return. “Thought you were never coming back,” she grumbled. “Of course I came back,” I said.

“NO LONGER MOURN FOR ME”

Memories of Olivia stayed with me after I had returned. Cousin Mary wanted to hear all about my visit and I told her. I mentioned that Jago had travelled up with me.

She laughed. “One can’t help liking Jago, eh?” she said. “No, of course one can’t. He’s a bit of a rogue but a charming one. I daresay he’ll be marrying soon.”

“He won’t have to be so concerned with bolstering up the family fortunes as his brother was.”

She looked at me sharply. “It’s a pity. Jago ought to have been the one to have done it. It wouldn’t have affected him half so much. He would have just gone on in his old way.”

“Would he have looked after the estate?”

“Ah, there you have a point. Well, it’s worked out the way it has and Jago will, I daresay, settle down in due course.”

She was looking rather slyly at me.

“He won’t with me,” I said, “even if he had the inclination—which I doubt.”

“I think he’s fond of you.”

“As I have said: and of every member of the female population under thirty and perhaps beyond.”

“That’s Jago. Well, well, it’ll be interesting. But he did go up to London remember. What did Olivia think of him?”

“Charming. But then she would be inclined to think everyone charming—and he was very pleasant.” I told her about Rosie and her comments.

She looked grave. “It would be in character, wouldn’t it? Yes, indeed it would. Well, there’s nothing you can do about it. Perhaps it’s a temporary embarrassment. I suppose people sometimes win. Otherwise they wouldn’t do it, would they? As for that woman … some nightclub hostess … that wouldn’t be serious and it’s inevitable, I reckon, with a man like that.”

Enthusiastically I described the baby. She gave me some oblique looks which I knew meant she thought I was hankering after one of my own.

I answered her as though she had spoken. She was accustomed to my reading her thoughts. “Being a godmother is quite enough for me.”

“You might change your mind.”

“I hardly think so. Unfortunately one can’t have a family without a husband and that is something I really can do without.”

“You’ll grow away from all that.”

I shook my head. “There are too many about like Jeremy Brandon.”

“Oh, but they’re not all like that!”

“My circle is rather limited, but in it there are two who sold themselves for a mess of pottage. Very nice pottage in both cases, I must admit. A fortune and a grand old house. Well worth while both. No. I have nothing to offer so there will be no suitors for my hand.”

“I wouldn’t be too sure of that.”

“I’m sure enough … and of my own feelings.”

“I’ve often thought that you could get rather bitter, Caroline. People do, I know … when these things happen to them. But it doesn’t do to judge the whole world on one or two people.”

“There is my mother. I doubt whether she would have found Alphonse so appealing without his money. Poor Captain Carmichael couldn’t stay the course, could he? He was handsome and charming … more than Alphonse.”

“You shouldn’t dwell on those things, dear.”

“I have to see the truth as it is presented to me.”

“Forget it all. Stop brooding on the past. Come out now. I want to go along to Glyn’s farm and then I want you to have a look at the books with me. Everything is getting very profitable. Very satisfactory, I can assure you.”

She was right. I threw myself into the work of the estate. I was becoming absorbed in it, and I realized how I had missed it while I had ” been away.

There came the occasional postcard from my mother. Life was wonderful. They were in Italy, in Spain and then back in Paris. Alphonse was such an important businessman. She was in her element. There were so many people who had to be entertained. Alphonse wrote to me and said he would be delighted for me to join them. There was always a home for me with them if I wished it. But at least why not come for a visit? He was as enamoured of my mother as ever and I imagined she was of use to him in his business. She certainly knew how to entertain and there was no doubt of his delight in his marriage. My mother was less pressing in her invitation and I gathered she did not want a grown-up daughter around to betray her age.

I would not wish to go with them. While I was working here with Cousin Mary I could forget so much which was unpleasant.

Soon after my return I rode out to the moors. It was my favourite spot. I loved the wildness of the country, the wide horizons, the untamed nature of the place, the springy grass, the clumps of gorse, the jutting boulders and the little streams which seemed to spring up here and there from nowhere.

The country was colourful—its final splash of colour as the year was passing. The oaks were now a deep bronze; very soon the leaves would be falling. There were lots of berries in the hedgerows this year. Did that mean a cold winter?

I rode almost automatically in the direction of the mine. It fascinated me. It looked so desolate and grim. How different it must have been when the men were working there!

I dismounted and patting my horse asked him to wait awhile; but on second thought, fearing he might not be able to resist the wild call of the moor, I tethered him to a bush and I went close to the mine and looked down.

It was eerie—due to the loneliness of the moor, I told myself. I took a stone and threw it down into the shaft. I listened to hear it hit bottom, but I heard nothing.

Paul was almost upon me before I heard the sound of his horse’s hoofs. He galloped up, dismounted and tied his horse to the same bush as mine.

“Hello,” I said, “I didn’t hear you approach until you were almost upon me.”

“I thought I told you not to go near the mine.”

“I believe you did. But I don’t have to do as I’m told.”

“It is as well to take advice from people who know the country better than you do.”

“I can see no danger in standing here.”

“The earth is soft and soggy. It could crumble under your feet. You could slide down there and call till you’d no voice to call with, and no one would hear you. Don’t do it again.” He had come close and he caught and held my arm. “Please,” he added.

I stepped backwards so that I was nearer to the edge of the mine. He caught me in his arms and held me.

“You see … how easy it is.”

“I’m perfectly all right.”

His face was close to mine. I felt weak, forgetting that he had married a woman for what she could bring him and that he was as mercenary in his way as Jeremy was in his.

He said: “I have wanted to talk to you for so long.”

I tried to release myself but he would not let me go.

“Come away from the mine,” he said. “I feel alarmed to see you so reckless.”

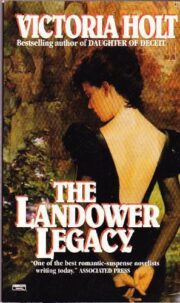

"The Landower Legacy" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Landower Legacy". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Landower Legacy" друзьям в соцсетях.