She was clearly changing the subject and as they started downstairs someone said to her, “I hear you will be at the Ponsonbys’.”

“I was kindly asked by Marcia Sanson. My little girls are so looking forward to it.”

The voices faded away.

I sat there for some time thinking: I believe that Captain Carmichael and my father do not like each other very much.

Then I crept into bed, felt my locket safe beneath the pillow and went to sleep.

We were up early next morning and Miss Bell was very careful with our toilettes. She had long pondered, going through our moderate wardrobes deciding on what garments would best do justice to our mother; she picked bottle green for me and crushed strawberry for Olivia. Our dresses were both made on the same lines with flounced skirts, decorous bodices and sleeves to the elbow. We wore long white stockings and black boots, and carried white gloves, and each of us had a straw hat, mine bearing a green ribbon and Olivia’s crushed strawberry.

We felt very smart. But when we saw our mother we realized how insignificant we were beside her splendour. She looked every bit the “beautiful Mrs. Tressidor.” She wore pink, a favourite colour of hers and one which was most becoming. The skirt of her dress was full and flounced and so draped to call attention to a waist, which in that age of small waists, was remarkable. The tightly fitting bodice further accentuated the charm of her figure; she wore a pale cream fichu at the neck which matched the lace at the cuffs of her sleeves. Her hat was the same mingling shades of cream and pink and perched jauntily on the top of her magnificent hair, while its cream-coloured ostrich feather fell over the brim and reached almost to her eyes as though to call attention to their sparkle. She looked young and excited and we all set off in a fever of anticipation.

The carriage was waiting for us, and Olivia and I sat one on either side of her as we rode out of the square.

The horses trotted along for a while and my mother suddenly called to the driver: “Blain, I want you to go to Waterloo Place.”

Blain turned in surprise as though he had not heard correctly. “But, Madam …” he began.

She smiled sweetly. “I’ve changed my mind. Waterloo Place.”

“Very good, Madam,” said Blain.

“Mama,” I cried, “are we not going to Lady Ponsonby’s?”

“No, dear. We are going somewhere else instead.”

“But everyone said …”

“Plans are changed. I think you will like this place better.”

Her eyes were brimming with mischief and an excitement gripped me. I had an inspiration. I had seen that look in her eyes before, and it recalled a certain person who, I believed, had put it there.

“Mama,” I said thoughtfully, “are we going to see Captain Carmichael?”

Her cheeks turned pink, which made her prettier than ever.

“Why? Whatever made you say that?”

“I just wondered … because …”

“Because what?”

“Does he live in Waterloo Place?”

“Close by.”

“So it is …”

“We shall get a better view there.”

I sat back in my seat. Something had been added to the day.

He was waiting to greet us, clearly expecting us. I thought it rather odd that we should have set out as for the Ponsonbys’ when this must have been arranged the evening before.

However, I was too excited to think much about it. We were here and that was all that mattered.

Captain Carmichael’s rooms were small compared with ours, but there was a lovable disorder about them which I immediately sensed.

“Welcome!” he cried. “My lovely ladies, welcome all.”

I liked being referred to as a lovely lady, but it clearly embarrassed Olivia, who was perfectly sure that the description did not fit her.

“You are in good time,” he went on.

“Which is absolutely necessary if we were to get here,” said my mother. “These streets will be closed to traffic soon.”

“The procession will pass this way on the outward journey to the Abbey,” he said, “but you will not be able to leave until after it has returned, which pleases me very much, since it will give me more of the most delightful company I know. Now let me show my beauteous ladies the seating accommodation, and I expect the girls would like to watch what is going on in the streets.”

He led us to chairs in the window from which we had a good view of Waterloo Place.

“The route will be from the Palace through Constitution Hill, Piccadilly, Waterloo Place and Parliament Street to the Abbey, so you are in a good position. Now I daresay you would like some refreshment. I have some very special lemonade for you young people and some little biscuits to go with it—a speciality made for me by my cook, Mr. Fortnum.”

My mother giggled and said: “I believe that to be incorrect. They were made by Mr. Mason.”

“Fortnum or Mason, what matters it?”

I laughed immoderately because I knew that Fortnum and Mason was a shop in Piccadilly, and Captain Carmichael meant he had bought the biscuits from them.

“I will come and help you with the lemonade,” said my mother.

I was astonished. The idea of her getting anything was so surprising. At home she would ring if she wanted a cushion for her chair.

They went out together. Olivia looked a little dismayed.

“It’s exciting,” I said.

“Why did we come here? I thought we were going to the Ponsonbys’. And what does he mean about his cooks? Fortnum and Mason is a shop.”

“Oh, Olivia,” I said, “you are so solemn. This is going to be fun.”

They were quite a long time coming with the lemonade and when they did, my mother had removed her hat. She looked flushed but very much at home, and she made a great show of pouring out the lemonade.

“Luncheon will be served later,” said Captain Carmichael.

I can still remember every moment of that day. There was a certain magic about it, a certain feeling of waiting, like the moment in the theatre when the curtain is about to go up and one is not quite sure what is going to be revealed. But I might have thought that afterwards in view of everything that happened, as one is inclined to do, looking back on important days in one’s life, imagining they were pregnant with foreboding … no, hardly foreboding. I felt nothing of that, only a tremendous excitement, as though something really important was going to happen.

There came the great moment when we could hear the approaching procession. I loved the Handel march; it seemed most appropriate; and there she was—a rather disappointing little figure and yes, in a bonnet. True, it was a rather special bonnet, made of lace and sparkling with diamonds, but nevertheless a bonnet. The cheers were deafening, and she sat there acknowledging them now and then with a lift of her hand, not so appreciative as I thought she might have been of this show of excessive loyalty. But it was a wonderful sight. Her carriage was preceded by the Princes of her own House—her sons, sons-in-law and grandsons. I counted them. There were seventeen in all; and the most grand among them was the Queen’s son-in-law, Crown Prince Fritz of Prussia, clad in white and silver with the German Eagle on his helmet.

There was procession after procession. I was thrilled by the sight of the Indian Princes in their magnificent robes sparkling with jewels. There were among them envoys from Europe, four Kings—those of Saxony, Belgium, Denmark and the Hellenes; and Greece, Portugal, Sweden and Austria—like Prussia—had sent their Crown Princes.

The whole world, it seemed on that day, was determined to pay homage to the little old lady in her lace and diamond bonnet, who had reigned for fifty years.

Even when the procession had passed, I still felt dazed by the spectacle; the music was still ringing in my ears, and I could still see the magnificently caparisoned horses and their brilliant riders while my mother disappeared with the Captain, having mentioned something about luncheon.

The Captain wheeled in a trolley on which was cold chicken, some crusty bread and a dish of butter.

He brought a little table to the window. There was just room for the four of us to sit at it. Deftly he covered it with a lacy cloth.

What a luncheon that was! Later I thought it was like the end of an era, the end of innocence. That delicious cold chicken was like tasting the tree of knowledge.

The Captain opened a bottle which had been standing in a bucket of ice, and he produced four glasses.

“Do you think they should?” asked my mother.

“Just a thimbleful.”

The thimblefuls were half glasses. I sipped the fuzzy liquid in ecstasy, and felt intoxicated with a very special sort of happiness. The world seemed wonderful and I envisioned this as the beginning of a new existence when Olivia and I became our mother’s dearest friends; we accompanied her on expeditions such as this one which she and the Captain between them conspired to arrange for our delight.

Crowds were beginning to gather in the streets below and now that the procession had passed the streets were no longer closed to traffic.

“On the return journey from the Abbey to the Palace she will go via Whitehall and the Mall,” said the Captain, “so the rest of the day is ours.”

“We must not be back too late,” said my mother.

“My dear, the streets will be impassable just now and will be for some time. We’re safe in our eyrie.”

We all laughed. Indeed, we were laughing a good deal and at nothing in particular which is perhaps the expression of real happiness.

The sound of voices below was muted and remote—outside our magic circle. Captain Carmichael talked all the time and we laughed; he made us talk too, and even Olivia did … a little. Our mother seemed like a different person; every now and then she would say “Jock!” in a tone of mock reproof which even Olivia guessed was a form of endearment.

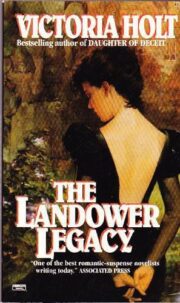

"The Landower Legacy" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Landower Legacy". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Landower Legacy" друзьям в соцсетях.