I hated her view of life and yet … I knew she was right when she said Olivia would be happy.

I could see my sister going through life seeing only good and being unaware of evil.

I could not destroy her illusions.

I went to my room that night and tore up the letter I had written to her.

But I felt the bitterness eating into my soul. I hated Jeremy Brandon a hundred times more than I had done before.

The Dubussons were giving a dinner party to which we were invited and although my mother despised their “little evenings,” as she called them, they did relieve the monotony and she would prepare herself for them—or rather Everton prepared her—with as much care as she had bestowed upon her London engagements.

She and Everton would be in close conference for a day or so deciding what she would wear, and her toilette would engross them both for several hours before our departure.

“Just a friendly little party,” Madame Dubusson had said. “A gathering of neighbours. The Claremonts have some important business client staying with them and I have asked them to bring him along.”

My mother certainly looked very beautiful when we were ready. She was wearing a gown of her favorite lavender colour and her delicately tinted skin and shining hair accentuated her beauty. She looked much as she had when we were in London and I thought, If a Dubusson dinner party can do this, she would soon be perfectly well if she could once again enter fashionable society.

Everton had insisted on doing my hair and I had to admit that she had done it very well. She had brushed it with a hair brush covered with some special silk and then piled it high on my head. She had selected an emerald brooch, belonging to my mother, which she had put on my grey gown; and Everton certainly knew what she was about.

The Dubussons had sent one of their somewhat decrepit old carriages for us. I saw my mother’s distaste as she seated herself and I had to remind her that it was good of the Dubussons to provide transport for us as we had none of our own; all the same her expression did not change when we entered the courtyard of the chateau, and she caught sight of a hen perched on one of the walls.

Madame Dubusson greeted us warmly. The guests were ourselves, Dr. Legrand and the Claremonts with their visitor.

“We all know each other,” announced Madame Dubusson, “except Monsieur Foucard.”

Monsieur Foucard came forward and bowed gravely. He was, I should say, in his middle fifties; he had a little goatee beard and sparkling dark eyes. His luxuriant hair was almost black and he was dressed with such elegance that one was immediately reminded of the lack of that quality in the other men.

He was somewhat fulsome. He was clearly rather startled by my mother’s good looks, which seemed to imply that he did not expect to find such elegance in this country community. He was equally gracious to me.

Madame Dubusson said we should have an aperitif and then dinner would be served.

It was clear that Monsieur Foucard was the guest of honour. He had a presence. There was no doubt of that. He had a way, too, of monopolizing the conversation. He seated himself between my mother and me and addressed himself mainly to us.

His stay was, alas, to be brief, he told us, and he was already regretting that. His eyes lingered on my mother. She seemed to sparkle; this was the sort of attention she so desperately needed. I was glad that she was enjoying this so much.

“You are a man of affairs,” said my mother. “Oh, I do not mean affairs of the heart. I mean business affairs.”

He laughed heartily, his eyes shining with admiration.

It was true, he admitted. He had business all over France. It meant travelling a good deal. Yes, he was in the perfume business. What a business! He had been brought up in it. “It is the nose, Mesdames. This nose.” He indicated his own somewhat prominent feature. “I was able to detect all the subtleties of good perfume almost as a baby. At an early age I learned of the wonderful perfumes which could be made to suit beautiful women. I knew that the best cedar wood came from the Atlas Mountains in Morocco, and the essential oil we get from cedar wood is invaluable to give that tang … shall I say to set a scent … It’s a fixative.”

“It’s fascinating!” cried my mother. “Do tell me more.”

He was only too ready, and although he turned to me now and then and addressed the occasional remark in my direction, I could see he was carried away by my mother’s mature charms.

I knew why my mother always found an immediate masculine response. She was entirely feminine. She looked frail and helpless; her large brown eyes appealed for protection; she put on an air of innocence, of ignorance, in order to flatter masculine superiority, and they loved her for it. What man would not feel himself growing in stature to be appealed to by such an enchanting creature?

She was now looking at him as though all her life she had been longing to discover the facts about the manufacture of perfume.

Madame Dubusson and the Claremonts were delighted to see that their important guest was enjoying the company so intensely.

The food was always excellent at the Dubusson table. Even my mother had to admit that. Eating to the Dubussons was a religion. The manner in which they attacked their food, the obvious relish with which they consumed it, exuded a kind of reverence. But I imagined that was a trait of the French in general rather than in particular. I was sure Monsieur Foucard was a typical Frenchman in that respect, but on that night he seemed far more interested in the company than the food.

My mother said: “You must tell us more about this fascinating subject, Monsieur Foucard.”

“If you insist, Madame,” he replied.

“I do!” she replied with an upward smile at him.

“At all costs Madame must be obeyed.”

And, of course, what he wanted more than anything else was to talk of his business and when it was at the request of such an elegant and attractive woman he was delighted.

He talked; and I admit it was interesting. I learned a great deal not only about the manufacture of perfume but its history. He was certainly knowledgeable on his subject and he talked of what perfumes the ancient Egyptians had used and he bemoaned the fact that at the present day perfume was not used to the same extent.

“But, my dear lady, we shall work on that. The presentation has been neglected. Things must look good, must they not, to please the eyes, and who is more insistent on that than the ladies? We are presenting them in such a way that they are irresistible. What is more delightful than a fragrant perfume?”

My mother laughed and halted him in his flow. “You speak too fast for me sometimes, Monsieur Foucard. You must remember that I am such a novice at your language.”

“Madame, I never heard my language more delightfully spoken.”

“You are as great a flatterer as a parfumeur.” She tapped his hand playfully, which made him laugh.

“I am going to ask a great favour,” he declared.

“I am not sure whether I shall be able to grant it,” she replied coquettishly.

“You must or I shall be desolate.”

She leaned towards him, putting her ear close to his lips.

He said: “I am going to ask you to allow me to send you a flagon of my very special creation. It is Muguet …”

“Muguet!” I cried. “We call that lily of the valley.”

“Lillee of the vallee,” he repeated, and my mother laughed immoderately.

“Madame is like a lily. It is the perfume I would choose for her.”

I felt that the evening was being given over to this flirtation between him and my mother. But no one minded. The kindhearted Dubussons liked to see people enjoying themselves; the doctor was intent on his food and that was enough for him. As for the Claremonts, they were delighted. They were greatly in awe of the important Monsieur Foucard and I guessed they relied on him to buy quantities of their . essences. The Dubussons were also delighted to see their guests taking over the burden of entertaining each other and making a very good job of it.

My mother and Monsieur Foucard were clearly getting more satisfaction from the situation than anyone.

We sat over dinner sampling the wines. Monsieur Foucard knew a great deal about them, but it was obvious that his real interest was in perfume.

There were signs of regret from Monsieur Foucard when the evening came to an end.

Effusively he thanked Madame and Monsieur Dubusson. The Claremonts exuded satisfaction and when Monsieur Foucard heard that my mother and I were travelling home in one of the Dubusson carriages he insisted on accompanying us.

This he did to my mother’s immense satisfaction.

The evening had been a triumph for her.

Monsieur Foucard kissed first my hand and then my mother’s— lingering over hers and looking into her eyes, he told her that he deeply regretted he must leave the next day for Paris.

“Perhaps I shall be returning,” he said, still holding her hand.

“I hope that may be so,” replied my mother earnestly, “but I have no doubt that you will find this little village somewhat dull after the exciting places and people you must be meeting all the time.”

He looked very solemn. “Madame,” he said, placing his hand on his heart with an elaborate gesture to indicate his complete sincerity, “I assure you I have never enjoyed an evening as I have this one.”

Everton was waiting for my mother and I heard their excited conversation going on into the early hours of the morning.

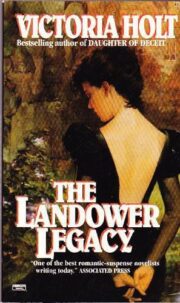

"The Landower Legacy" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Landower Legacy". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Landower Legacy" друзьям в соцсетях.